“Society must be prepared”

At Arctic Frontiers, European health researchers discussed how climate changes in the Arctic might cause future pandemics. They agreed that global health challenges should be addressed with a broad and holistic approach.

This year, UiT has taken over the leadership responsibility for the university alliance EUGLOH. The goal of the alliance is to facilitate education, innovation, and research, at a multilateral and interdisciplinary level, which can solve global health challenges.

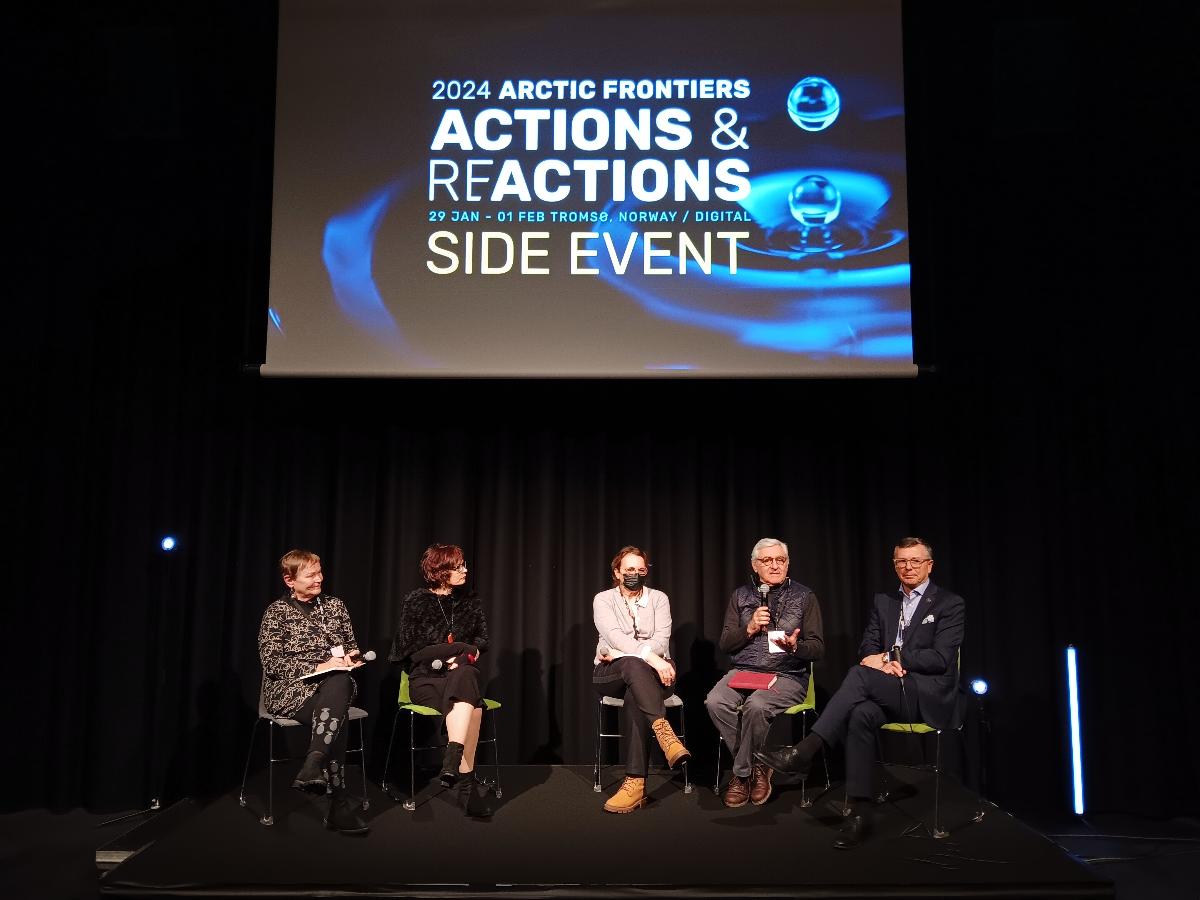

The takeover of the leadership was marked by UiT hosting a panel discussion at the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsø, on January 29th. The moderator for the debate was UiT's rector, Dag Rune Olsen, and the event was titled: "Solutions for One Health issues in Europe and the Arctic". Panel participants and speakers were researchers from EUGLOH partner universities such as Université Paris-Saclay, University of Porto, and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Solving global health challenges

They came to discuss how the One Health concept can provide new perspectives on how to solve global health challenges. The concept involves an integrated, systematic, and united approach to supporting better health for animals and humans, but also sustainable health at a local, national, and global level.

In his introduction, UiT's rector Dag Rune Olsen emphasized that Northern Norway faces its own challenges in building sustainable communities and healthcare systems, where there is a relatively small population and vulnerable ecosystems. This point also touched on the main theme of the event:

“It is important that we do not decouple the importance of health for ecosystems with human health. It is interwoven, it is not detached from each other”, Olsen emphasized.

He acknowledged that it can be easy to lose sight of the complex health challenges we face on a global scale. But he added:

“The broader university community across many borders of this globe possess huge amounts of knowledge about how to tackle these problems. It is not necessarily knowledge, science and lack of insight that we lack. But it is a challenge how to bring this knowledge together, to see how can develop new strategies.”

Facts about climate change and health

- Climate change leads to heatwaves, wildfires, floods, and tropical storms that are increasing in scale, frequency, and intensity.

- Extreme weather has caused damage and increased mortality in various places on Earth.

- This results in more humanitarian emergencies than before.

- A changing climate also causes respiratory diseases, waterborne diseases, and diseases transmitted from animals to humans.

- 3.6 billion people live in areas that are highly vulnerable to climate change.

- Inadequate infrastructure leaves populations poorly equipped to prepare for and handle the repercussions of climate change.

- There are also major challenges related to malnutrition, food security, diseases linked to food production, and mental health.

- Vulnerable groups include young children, the elderly, and those with chronic diseases, low income, living isolated in communities or in rural areas, and climate refugees.

Climate change is already placing human health at risk in every region of the world.

Climate change as a health threat

The COVID pandemic is the foremost example of how health systems can meet a global health challenge through complex coordination on multiple levels. But this may just be the beginning of what's to come. Due to the melting of the ice in the Arctic, new pandemics could be triggered, and new humanitarian emergencies will arise as a result of extreme weather in the form of heatwaves, extreme precipitation, drought, and floods.

At Arctic Frontiers, Elisabeth Delaroque-Astagneau, professor at the Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (UVSQ)/Université Paris-Saclay, outlined the seriousness of the impending challenges.

“Climate change is already placing human health at risk in every region of the world”, said Delaroque-Astagneau.

She believes this is clearly evident from the fact that the WHO concludes that climate change is among the most serious threats to human health in this century.

Transmission of disease from animals to humans

Delaroque-Astagneau also emphasizes that Europe can be greatly affected by health problems caused by climate changes on a global scale. 75 percent of all emerging infectious diseases are related to zoonosis, or transmission from animals to humans, Delaroque-Astagneau pointed out. She believes it is crucial to increase knowledge about ecological systems, establish robust health systems, and develop research models that can provide new knowledge about transmission between animals and humans. In addition, she recommended that we should expand the monitoring of areas on Earth with increasing health risks.

But she believes there are also other challenges that are not related to access to health resources. For her, an important point is that the WHO regards vaccine resistance as one of the ten greatest threats to global health.

The most important thing that each country can do, according to Delaroque-Astagneau, is to establish resilient health systems that can prepare, absorb large shocks, and then implement measures so a society can return to a normal state after pandemics. She believes Norway is well-positioned in this area as we are at the top of the statistics when it comes to the number of doctors and nurses per 1000 inhabitants.

“Society must be prepared. We need to increase what we call health literacy. And we also have to reflect on our health social inequalities in a societal perspective. Because that was a huge problem during the Covid 19 pandemic. I think it is very important to be European. I think the European response to the next pandemic is also the next challenge”, Delaroque-Astagneau concluded.

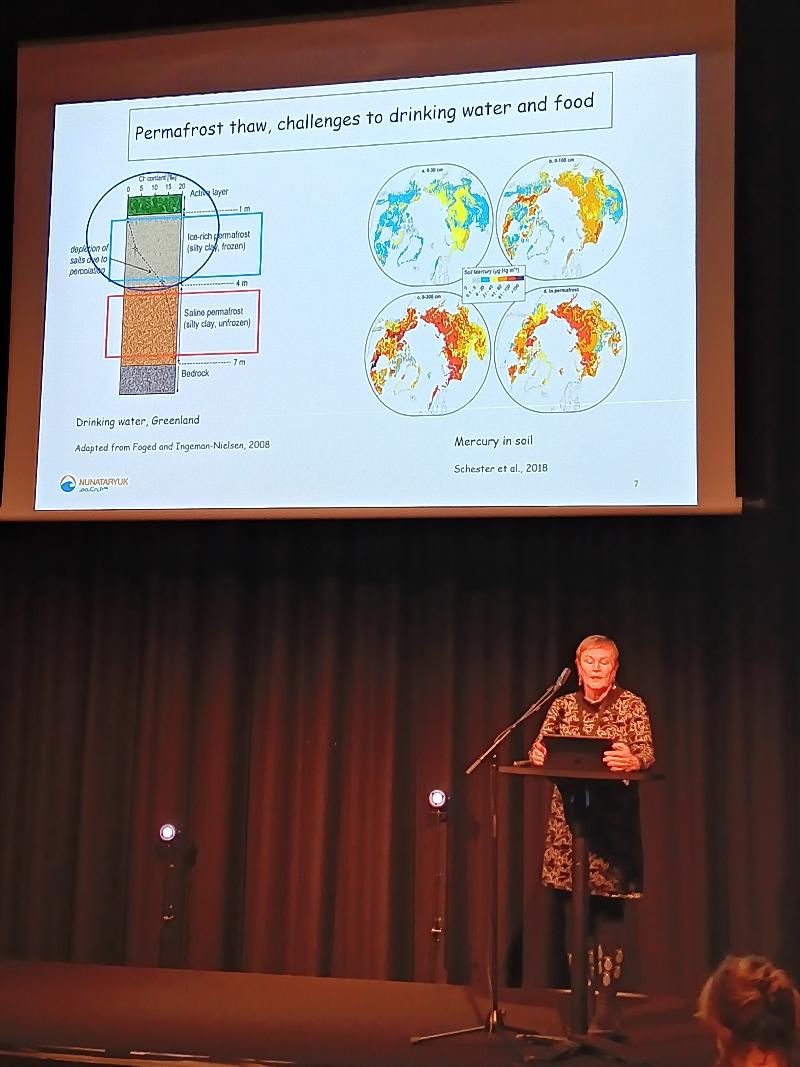

The threat beneath the ground

Arja Rautio, professor at the University of Oulu, presented at Arctic Frontiers a research project on how the thawing of permafrost poses a threat to global health. She points out that in 2017, 7.1 million people lived in the Arctic in areas with permafrost. By 2060, it is estimated that 3.3 million people will live in areas where the permafrost has thawed. If this happens, it could destroy infrastructure, hinder food production, poison drinking water, and spread diseases from animals to humans.

Rautio believes that both a halt in CO2 emissions and close cooperation between the local population and authorities are necessary to counteract the development we see today. But according to Rautio, it also requires that new measures be taken within research.

“Infectious diseases and new species don’t recognize borders. We need this systematic approach, we need the mixed methodology. Artificial intelligence can help us reveal what we cannot see for ourselves. We have a huge amount of data and we need to use that to improve the health of individuals, the people and communities”, Rautio pointed out.

Infectious diseases and new species don’t recognize borders.

Changes in attitudes

Henrique Barros, professor at the University of Porto, emphasized the complex challenge humanity faces when it comes to upcoming pandemics. For him, it is important that health researchers do not follow what he describes as a "reductionist approach." According to Barros, this means emphasizing only a few, simple solutions and explanations for health challenges, or examining the health of animals and humans separately.

“We forget that when we try to fix something, often we are getting other things in trouble. I think it is time to respond to complex questions using complex systems approaches”, Barros said. He expects that Europe's health systems will be faced with enormous challenges in the future.

“The major challenge is to predict, but not to wait for the problems, but try to change the situation that will end in a certain condition. Then you don’t need to run after vaccines or medications”, Barros stated.

Like Delaroque-Astagneau, he believes that more resilient health systems should be built and that perspectives from social sciences should be brought back to a greater extent within health research. He also pointed out that fundamental behavioral and attitudinal changes are crucial.

Barros finally issued a message of concern to colleagues around the world:

“There is a problem of trust. If we don’t trust, if we look at science as any other thing that can be true or wrong, and that we can say whatever we want, it will make it difficult to face new challenges”, he concluded.

-

Fiskeri- og havbruksvitenskap - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Fiskeri- og havbruksvitenskap - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Akvamedisin - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Bioteknologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Arkeologi - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Musikkteknologi

Varighet: 1 År -

Peace and Conflict Transformation - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Computer Science - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Geosciences - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Biology - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Technology and Safety - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Physics - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Mathematical Sciences - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Biomedicine - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Public Health - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Computational chemistry - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Law of the Sea - master

Varighet: 3 Semestre -

Biologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Medisin profesjonsstudium

Varighet: 6 År -

Nordisk - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Historie - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Luftfartsfag - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Pedagogikk - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Arkeologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Bioingeniørfag - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Pedagogikk - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Informatikk, datamaskinsystemer - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Informatikk, sivilingeniør - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Allmenn litteraturvitenskap - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Likestilling og kjønn - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Historie - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Geovitenskap- bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Biomedisin - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Psykologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Samfunnssikkerhet - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Matematikk - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Ergoterapi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Fysioterapi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Radiografi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Automasjon, ingeniør - bachelor (ordinær, y-vei)

Varighet: 3 År -

Samfunnssikkerhet - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Kunst - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Kunsthistorie - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Farmasi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Farmasi - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Religionsvitenskap - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Romfysikk, sivilingeniør - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Sosialantropologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Bærekraftig teknologi, ingeniør - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Forkurs for ingeniør- og sivilingeniørutdanning

Varighet: 1 År