NORMEMO autumn 2022 guest lectures - please join us online or onsite!

The NORMEMO guest lectures series is devoted to uses of history and memory politics in Russia and neighboring states. The series includes some of the foremost international experts in the field as well as younger researchers.

The lectures are free and open to a general audience.

Venue: Zoom / Aase Hiorth Lervik room (N-119) Breiviklia, UiT the Arctic University of Norway

Thursday 25 August, 14.15-16 CET:

Olga Davydova-Minguet: Victims on display. The instrumentalizations of the memory of Finnish concentration camps in the Russian Republic of Karelia

Russians’ support for Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has its roots, among others, in the post-Soviet resentment and feelings of victimhood. The production of the image of Russia as a victim of the “West” started already in the 1990s and was enhanced in the 2010s in the “memory wars” with the Baltic states, countries of Central Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics, such as Ukraine. Finland has remained on the sideline of these memory wars, but there are several smouldering memory conflicts that are now being developed in the confrontational direction.

The lecture analyses how the Second World War’s concentration camps organized by Finnish military administration have been present/ed in the public memory of the Russian Republic of Karelia. These camps were organized for the so-called non-national (i.a. Russian) population during the occupation of Karelia in 1941-1944 by the Finnish military administration. Approximately half of the population which remained in the republic after the evacuation in the autumn of 1941 did not belong to ethnicities which were considered by the occupants as close to Finns, such as Karelians and Vepsians. During the occupation, about 24 000 Russians were imprisoned, and about 4 000 died in the camps. After the war, the concentration camps and their prisoners were “forgotten” in the official public memory in Karelia, and the first memorial appeared only 25 years after the war. Still, during the Soviet era, this memory remained “peripheral”, as well as the image of Finland as an occupant.

In the post-Soviet period, this memory became an asset of the organization of former juvenile prisoners of the camps. Through making the memory of Finnish concentration camps visible in the city of Petrozavodsk, the organization participated in the “post-Soviet moral economy of guilt and debt” (Zhurzhenko 2018). The organization opposed neoliberal social reforms by bringing forward its members’ sufferings as victims of both Fascism (simultaneously equating Finns to Fascists) and the Soviet and Russian state (which didn’t recognize their “feat of survival” during the war).

Since 2014, this memory entered official, state-controlled spaces and places, such as museums, exhibitions and state-aligned media. In 2017, a flamboyant memorial to the victims of concentration camps was constructed on the cemetery where they were buried; in 2019 a movie about the children of the camps was issued, and after that the scenery of the movie was erected in one of the Karelian villages as an educational centre for children. In these activities, the “ownership” of this memory shifted from the organization of juvenile prisoners to the actors conveying state memory politics, where Russia and Russians are presented as victims, not only as winners.

Join Zoom Meeting:

https://uit.zoom.us/j/69012750327?pwd=MGhMSFBOVnBUZ05Sa2VtUEduNlFMdz09

Olga Davydova-Minguet holds a professorship of Russian and border studies with the Karelian Institute of the University of Eastern Finland. Davydova-Minguet’s main research interests fall within the intersection of migration, cultural and transnational studies. She has studied immigration of Russian-speakers to Finland since the beginning of the 2000s. Recently, she has conducted three research projects, concentrating upon the transnational politics of memory in the border areas of Finland and Russia; the media use of the Russian-speakers in Finland; and the images of Russia in Finland. Her current main project delves into death practices among Russian-speaking immigrants in Eastern Finland, and the meanings of death in memory politics in the bordering Republic of Karelia in Russia and Eastern Finland.

Thursday 15 September, 14.15-16 CET:

George Soroka: Russia and the Rest: Imperial versus National Memory in the Post-Communist Space

Memory has increasingly been legislated and securitized in recent years throughout the post-communist world. At the same time, its trans-border aspect has been emphasized more and more, as evinced in the civilizational rhetoric regarding history surrounding Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Grounded both theoretically and empirically, this talk explores the main dimensions of how Russian "imperial" memory has manifest in the post-communist region and how it has been countered by the proliferation of "national" memories among Moscow's former subalterns.

George Soroka is Lecturer on Government at Harvard University, from where he holds a PhD in political science. His work focuses on the politics of history in the post-communist region, Arctic security, and religion and politics. He has published in a number of outlets, including East European Politics and Society, Problems of Postcommunism, Foreign Affairs, and the Journal of Democracy.

Thursday 30 September, 13.15-15 CET:

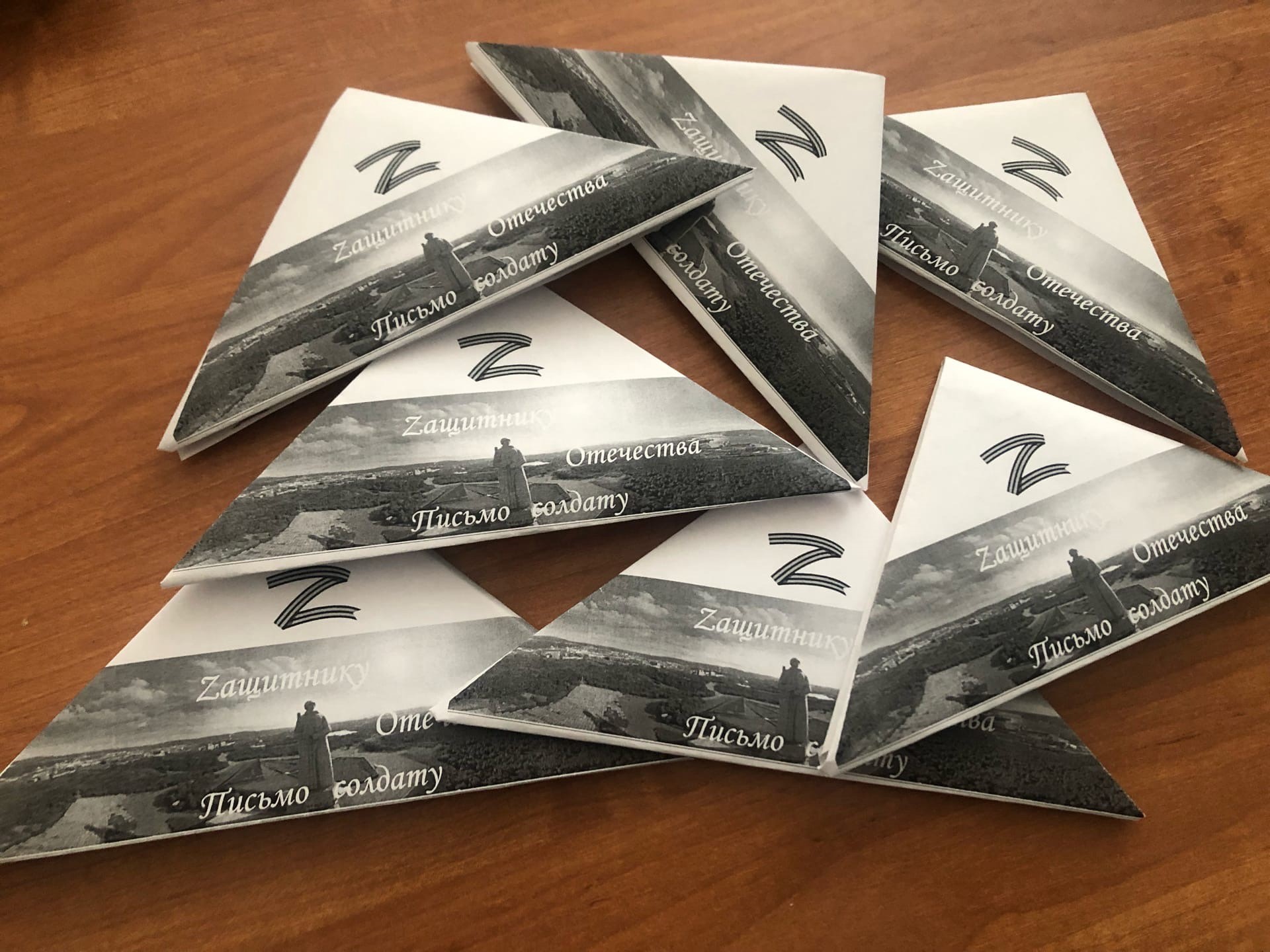

Håvard Bækken: Merging wars: The wartime exploitation of the Great Patriotic War in Russian military patriotic clubs

The lecture examines the exploitation of war memories within military patriotic youth clubs in the Russian High North. The activities and shared material posted on local social media accounts suggest a widespread practice of symbolically merging the warfare in Ukraine with the Great Patriotic War (GPW). The “war merging tools” include brief statements, symbol use, visual imagery and contextualization. Rarely referring to historical events except at a great level of abstraction, war merging instead appeal to internalized narratives and emotional attachment to the GPW. The practice dominates the military patriotic clubs coverage of the ongoing war, and most declarations of support of Russian troops is filtered through its quasi-historical lens. In lack of actual information, many Russian children may thus experience the ongoing war primarily though state-approved symbols of historical origin.

Join Zoom Meeting:

https://uit.zoom.us/j/67808942140?pwd=VnFmU0NZOGtKRVBkZGRGcFhNRWNVZz09

Håvard Bækken is a NORMEMO project participant, and a senior research fellow at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies. He has a PhD in Russian Area Studies. His current research focus is memory politics, militarism and military patriotic education in Russia. Recent publications include Guns and glory: A dualistic perspective on resurgent militarism in Russia (2022); Patriotic disunity: limits to popular support for militaristic policy in Russia (2021); Identity under siege: Selective securitization of history in Putin's Russia (2020); The return to patriotic education in Post-Soviet Russia: How, when, and why the Russian military engaged in civilian nation building (2019). Bækken has also published on quasi-legal repression in Russian politics, and is the author of the book

Law and power in Russia: Making sense of quasi-legal practices (2019).

Thursday 10 November, 12.15-14 CET:

Maria Mälksoo: Deterrence by Other Means: The International Politics of Domestic Memory Laws

This lecture investigates how memory laws that regulate the legitimate frames of remembering the past of righteous and perpetrators function as devices of deterrence in states’ (inter)national memory politics. I conceptualize mnemopolitical deterrence and assess the aims and sought effects of various memory laws in the Central and East European space.

Engaging deterrence scholarship in International Security Studies and legal studies, the lecture unfolds and contextualizes the international aims, the projected and (thus far) observable effects of the memory laws that criminalize, discipline and punish the accounts of the past deemed undesirable to a particular state identity in Russia, Poland and Ukraine. I argue that besides defining acceptable and (un)desirable boundaries of political subjectivities, punitive memory laws do performative work by signalling political intent to defend a particular “state’s story” of the past in the international sphere.

In their distinct ways, the memory laws of Russia, Poland and Ukraine have emerged as international, not just domestic memory-political dissuasion devices in the manifold contestations over the legitimate remembrance and “right” narratives of their respective nation’s role in the Second World War and/or the Holocaust. Mnemopolitical deterrence is illustrative of the ritual logic of action underpinning deterrence practices in state ontological security-seeking.

Join Zoom Meeting:

https://uit.zoom.us/j/63507515543?pwd=MnhHNEdCYkR6eXplUEk1alVBWW5UQT09

Maria Mälksoo is Senior Researcher at the Centre for Military Studies in the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. Mälksoo’s research foci are in Critical Security Studies (ontological security, securitization of historical memory, hybrid warfare); political anthropology (liminality, rituals), and the social study of deterrence (with a focus on NATO’s eastern flank). Dr Mälksoo is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council's Consolidator Grant RITUAL DETERRENCE (2022-2027) and leads the Baltic chapter of the collaborative MEMOCRACY project, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation (2021-2024). Besides numerous academic and popular articles, she is the author of The Politics of Becoming European: A Study of Polish and Baltic Post-Cold War Security Imaginaries (Routledge, 2010); a co-author of Remembering Katyn (Polity, 2012); an editor of the JIRD Special Issue “Uses of ‘the East’ in International Studies: provincializing IR from Central and Eastern Europe” (2022) and the Handbook on the Politics of Memory (Edward Elgar, forthcoming 2023).

Friday 9 December, 15.15-17 CET:

Anton Weiss-Wendt: Putin's Regime Hijacking the Holocaust: History Politics as an Element of Soft Power

Since recently, Russia has emerged as a major player in the field of Holocaust remembrance. Putin's regime has been construing an alternative, popular Holocaust narrative, complete with own commemoration dates, NGOs, motion pictures, and exhibitions. The regime has also incorporated the Holocaust into foreign policy, making it essentially an instrument of soft power. The Holocaust is now a part of the Russian history politics, coordinated at the highest government level.

The present Russian discourse on the Holocaust is surprisingly similar to the late Soviet. Jews are once again primarily identified by their nationality rather than their ethnicity and/or religion. Notably, the Russian officials, like the Soviet before them, shy away from referring to the Holocaust as genocide. The portrayal of the Holocaust on screen and in exhibition halls is typically based on secondary sources, with no comprehensive primary research involved. The professionalization of Holocaust research never came to be. Most of the scholars doing research on the Holocaust in Russia come from within the Jewish community. Hence, the scholarship produced inside Russia does not become integrated in an international field of Holocaust studies. References to the mass murder of Jews serve purposes other than an accurate historical representation or genuine commemoration. Until recently, the focus on local collaboration in the Nazi genocide of the Jews served mainly to ruffle East Europeans' feathers. The focus has now changed to emphasizing the decisive role of the Soviet Army in the liberation of surviving Jewish prisoners and bringing salvation to the Nazi-savaged Europe. This serves the single goal of fashioning the (Soviet) victory over Hitler's Germany as a central event in world's history.

The Russian Government makes considerable efforts to promote this take on the Holocaust internationally. Individuals who have been instrumental in projecting the official Russian position on the Holocaust abroad have all in one way or another benefitted from state largesse. Wittingly or unwittingly, they became a part of the patron-client system of governance instituted by Putin in Russia. In recent years, the Russian Foreign Ministry has displayed certain finesse in presenting its perspective on the Holocaust. This goes hand in hand with the potential of soft power rediscovered by Moscow since the 2011-12 pro-democracy protests in Russia and particularly in the aftermath of the military aggression against Ukraine in 2014.

Join Zoom Meeting

https://uit.zoom.us/j/67269477657?pwd=VWxqc3BEOTBXTnIrMDNJeUtYeGZ1QT09

Anton Weiss-Wendt is Research Professor (Forsker I) at the Norwegian Center for Holocaust and Minority Studies in Oslo. He holds a PhD in modern Jewish history from Brandeis University. He works mainly in the field of Holocaust and genocide studies. He is the author and/or editor of eleven books, including The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention (2017); A Rhetorical Crime: Genocide in the Geopolitical Discourse of the Cold War (2018); Putin's Russia and the Falsification of History: Reasserting Control over the Past (2020), and (with Nanci Adler) The Future of the Soviet Past: The Politics of History in Putin's Russia (2021).