50 artworks

A colourful tapestry fills the entire wall towards the Aula at The Music Conservatory in Tromsø. The woven textile is more than 40 square meters in size and composed of seven fabrics that partially overlap each other and appear as an expressive whole through its repeated shapes and colours. The lower part has free hanging pieces in different lengths and different colours, which reminds of tangents, or of fringes and festive fanfare. In the middle parts the large colour fields in black, blue, violet, pink and yellow are folded out as abstract parallelograms, or as sails, against the warm red background. The upper fields of the tapestry are linked by horizontal colour fields in blue, pink, orange and black, quite similar in its form to the kid’s drawings of V-birds or mountain peaks. Overlapping, the simplest way artists create the illusion of depth, is used both in the physical fabric and in the colour surfaces, thus enhancing the tension between surface and depth, as well as between abstraction and figuration, which in recent times has been a challenge in the monumental wall decoration. In this tapestry the abstract composition of strong, cohesive and repeated colour fields competes with our associations to a landscape of distant blue and of midnight sun, of birds and mountains.

Some have observed and theorized a strong connection between the colour of the image and the timbres of the music. The visual artist constructs either figurative or abstract pictures with colours and shapes, lines and surfaces in the same way as the composer uses tones and sounds of various instruments in tonal or atonal compositions. But while the music is committed to time, to succession, the picture is committed to space, juxtaposition, and to the corpus. In this woven picture, the Norwegian textile artist Åse Frøyshov (born 1943) colligates picture and music, underscored by the art work’s title, Fanfare. This is one of two monumental works made specifically for the new Music Conservatory Building in the southern part of the Tromsø island (1986). Frøyshov has made several such monumental and non-figurative tapestries where the composition of large colour fields and different yarn qualities gives strong and sensible impressions.

Elin Haugdal, Professor of Art History, Uit The Arctic university of Norway

Essen 1960 (also known as cabbage, Essen theme «Photooptische Abbildung» and student work) is a student work by Kivijärvi while he was studying “subjective photography” under Otto Steinert in Germany during the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s. The photo is reminiscent of a photo of a cabbage leaf from 1931 by the American photographer Edward Weston. In line with other contemporary artists of the 1930s, Weston was occupied by exploring the specific characteristics of the medium that he was engaged in. For example, it dealt with how to take advantage of the possibilities made the sharp focus and unusual angles of the photo medium – photography should contribute to a new way of seeing things. Weston often isolated artefacts from everyday life and displayed them in an even and sharp focus giving a precise rendering of details. Just as Kivijärvi did it in Essen 1960, Weston had been experimenting with the effects of light- and shadow. Contrary to Weston, though, Kivijärvi was less occupied by identifying something purely photographic. After a while he became known for his graphic style with strong contracts between the complete black and the complete white, making the motifs appear as if they were growing out of darkness. Even if Essen 1960 appears as less dramatic than his other works such as Trålegaster, Svalbardbanken and Fra de store banker, the motifs are recognized by a spesific kind of calm obtained by Kivijärvi’s way of balancing the motifs of his compositions. The spesific individuals and places of Kivijärvi’s pictorial universe are important. Nevertheless, he is allways expressing something of general importance to every human being.

Hanne Hammer Stien, Ph.D. in art history, University lecturer, UiT The Arctic University of Norway

Fifty meters long, the wall painting is flowing in meanders along the glass façade of the Pharmacy building. It is visible from the corridor of the vestibulum as well as from the atrium on the outside. Like a river that is running through falls, rapids and quiet parts, the painting is adapted to the stairs of the corridor. A common feature in the art of Thor Erdal (1951–) is strong colors displayed in expressive contrasting color fields. Many of his works are narrative, and often the landscape of Lofoten is a point of departure. The earliest of his works were figurative, the latest are characterized by more symbolic and abstract geometric forms. The river of life is dominated by strong color fields of red, blue, yellow and green constituting an abstract landscape, and occasionally of seemingly manmade structures. In some parts of the picture houses, towns and boats, as well as mountains, meadows and lakes are indicated. The last part of the picture's narrative and the lowest part of the painting displays several small circular shapes floating together in an overlapping pattern, almost like amoebas seen in a microscope. Are they perhaps referring to organic materials from the decomposition of life, or to the disciplines of biology, medicine and pharmacy? As an overstretched patchwork of expressive color contrasts, the painting might also appear as a stuffed toy, an alien to the firm design of the Pharmacy building. Nevertheless, its compositional and narrative characteristics are not far from Britta Marakatt-Labba's narrative tapestry from a Sámi context, Historja (2007) in the Sun Hall ("Solhallen") at the campus. In ancient Greece the temples were decorated by the frieze, a horizontal field running on the top of the columns, where lapiths, centaurs and other mythological creatures were fighting each other. The river of life is a frieze adapted to a Northern-Norwegian landscape in a contemporary visual language.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

Titled Kvile (Rest), Per Inge Bjørlo’s large black-and-white linocut on paper features above a set of firm, red sofas in the university café, Kaffebaren C8H10N4O2. The work’s dark colour, which is repeated in much of the café’s interior, as well as the composition’s dominating form, somewhat in the shape of a coffee bean, make Kvile a fitting piece of art in this space. Moreover, the work’s title, which points to the reclining human figure enclosed in a lemon shaped oval – perhaps a boat? – on a calm sea at night, ties in with the café’s function as a place to relax. While there is much in Bjørlo’s composition that may be associated with calm and rest, however, the image is somewhat unsettling and disturbing. Contributing to this notion is the ambiguous use of perspective, which on the one hand presents an impossible combination of two views – the first towards the horizon and the second straight down into a boat containing a person. Alternatively, there is only one perspective and our view is an underwater scene with the boat – a symbol of shelter and safety – instead being the cross-section of a claustrophobic human capsule. The diagonal orientation of the human figure, which is heavier at the top, creates a sensation that the figure will fall down or towards the viewer standing in front of the work. With legs gathered and arms resting on the stomach, the figure resembles a buried person, while the compact body is in part reminiscent of a skeleton or x-ray image. Like many of Bjørlo’s works, Kvile explores the darker side of human existence and is a somewhat uncomfortable reminder of our vulnerability and transience.

Ingeborg Høvik, associate professor in art history, ISK, UiT The arctic university of Norway

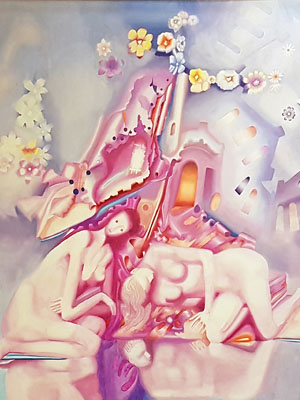

The painting is displaying a disintegrated world. People are overpowered by destruction and war. The formal language is abstract. Organic shapes of pastels in hues of pink in the central field are surrounded by varieties of lilac and light blue. Initially, the effect is idyllic. Nevertheless, a compact group of glazed and metallic fragments in the central field is giving associations to war machinery and ruins. A flower in the barrel of a gun is a symbol of piece. Other flowers are drifting in the airy pictorial space. Underneath the dense concentration of metal fragments two women are kneeling under the heavy burden. They are lying on their knees on a shiny surface reflecting their white and luminous bodies. One of them is almost totally bent, while the other is lifting her head, facing us with a confronting gaze. The picture is panted with acrylic colors; thus, it has a shimmering as well as a radiant character.

In all of his adult life Ekeland was a declared communist devoted to the living conditions of the individual in a marital world hostile to humans. As an artist, he was dedicated to expressionism and surrealism. Mirage have several expressionistic and surrealistic qualities. Some of its primary features are the contrasts between hard metal and soft human flesh (and flowers), and between superiority and powerlessness. The picture was painted in 1984 during the cold war when there was a general fear of nuclear conflict. Global annihilation and ecological destruction was a part of this.

Drifting Flowers and a flower in the barrel of a gun are almost predictable symbols, but in Mirage they are effective. They articulate a kind of optimism in a world of war, destruction and ecological crisis.

The painting is hanging on the wall in in the auditorium of MH-bygget.

Audhild Olaisen, Art historian

Henry Bardal's monumental work Untitled from 1984, occupies the entire wall at the entrance of the Science Building’s auditorium, only the doors to the left and right break the wall. In the literal sense, they act as entrances to the auditorium, in the pictorial sense they may be seen as portals into Bardal's narrative. The integration of the decoration in the room and the low perspective, with the baseline level with the top of the stairs, veritably invites the viewer into the image, it is as if we can "penetrate the wall" and take up position on the quayside alongside the groups of figures with their backs turned. Their attention is focused towards the middle ground, with the fully loaded fishing boat heading for the quay. Standing in the midst of the boat, the fisherman is ready to take off his oilskin jacket and step onto the quay. The boat's movements have formed ripples on the surface of the water, as parentheses they frame, isolate and emphasize the depiction of a traditional livelihood. Towards the background of the picture we see a number of fishing boats that move past a towering construction - an oil platform. Bardal’s fresco thematizes both the changes in Norway's livelihoods, from traditional fisheries to oil extraction, and technological developments, from the simple fishing boat to the oil rig.

The Science Building was completed in 1979, as one of the first buildings on the Breivika campus. Artists with north-Norwegian association were invited to participate in the competition for the decoration of the auditorium's entrance area. The choice fell on Henry Bardal (1919–2000), born and raised in Sandessjøen. In his work he was keen to represent the region’s nature and lifestyle. Formally, his work is characterized by the interwar period’s interest in mathematically designed compositions, as expressed through the many monumental decorations that were executed in Norway in the period 1918–50. With the decoration’s integration in the architecture and the subject's connection with the function and geographical location of the building, Bardal's work is undeniably placed in the extension of a central period in Norwegian art history – the Fresco era.

Hege Olaussen, assistant professor of art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

“Cleanup”, a photograph by Jim Bengtson (USA, 1942 -), is hanging above the waiting area’s sofa at the Arctic University of Norway’s Institute of Psychology (Teorifagbygget). The artist has captured the motif during one of his city walks and is an example of “street photography”. A young woman is displayed sitting partly on her knee, while vacuum cleaning in a showcase. The showcase, including the girl and a Hoover, is the main element of the composition. A blue sky filled with decorative butterflies is painted on the background. From a distance, the subject is reminiscent of an aquarium with its blue background and lights flashing through the window, but at close distance, it resembles a butterfly cage. The impression is disturbed by the girl and the vacuum cleaner. The motif turns up to be an empty showcase, and thus it is the girl and the vacuum cleaner that are exhibited. The beholder is successively surprised as he or she is getting closer and the meaning of the motif is changed. In addition, the window reflection of cars in the street is an urban contrast to the butterflies in the back of the showcase.

The picture is an example of the artist’s way of working: “I am searching for scenes in the world as it is; from its own theatre”, he says. The motif is not arranged, or made in a studio, but its effect is theatrical – intended, but not staged.

“Cleanup” is like a picture in a picture as it captures a young woman executing an ordinary task, but she herself is part of the exhibition. The photograph is an artistic statement about the professional activity at the Institute of Psychology. The woman in the showcase is observed twice: by people passing by on the street (at the time the picture was captured) and by the beholders of the photograph. Simultaneously, she is in her own world, occupied with her own task, but enclosed behind the window, and herself a part of the exhibition.

Silje B. Johannessen, Art Historian and Librarian, Tromsø Library and City Archives

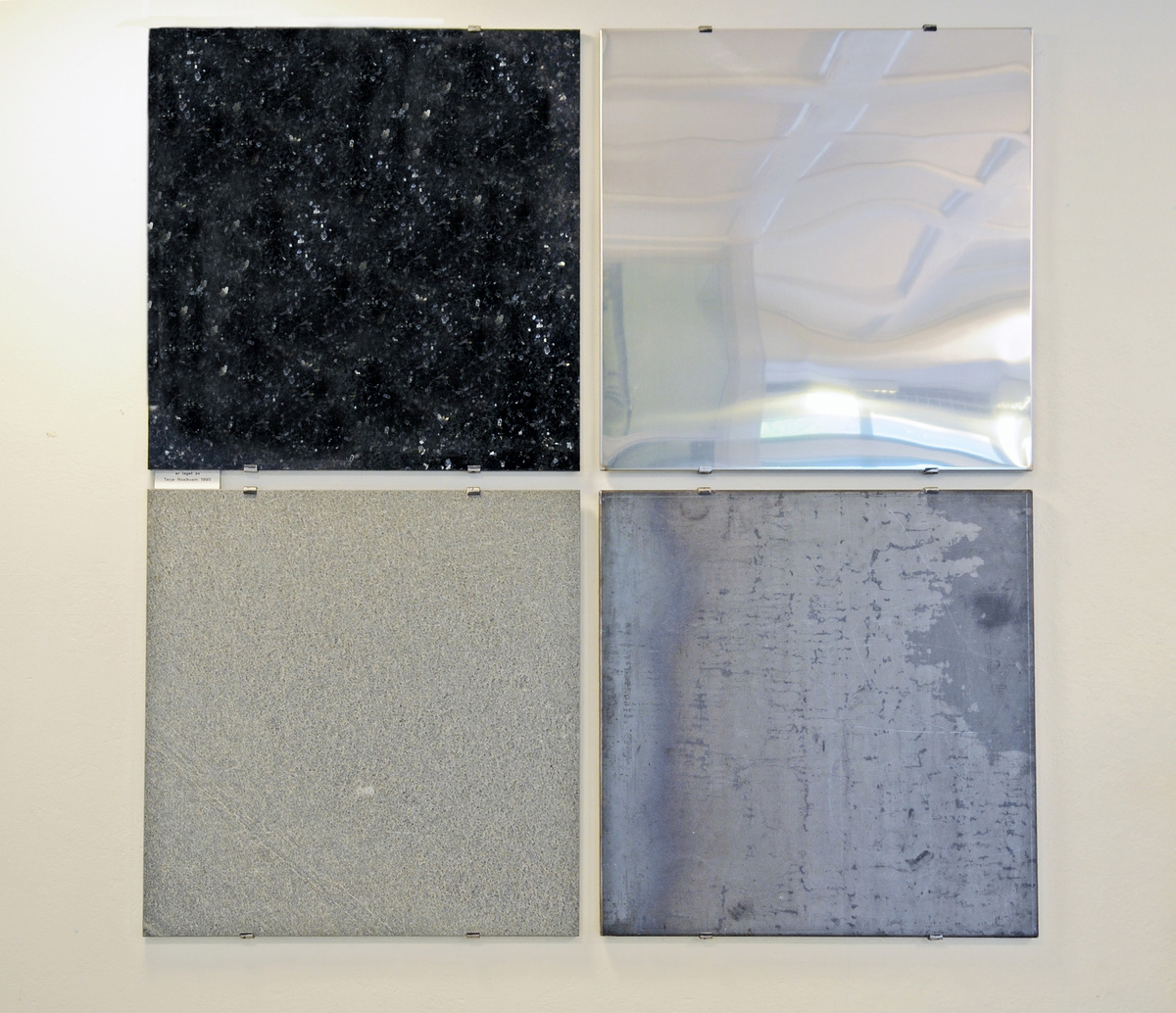

At extreme temperatures and under tremendous pressure the materials that constitute the wall installation Tablets (square) have been forged. All that force, created by nature, or by the human hand as such, has now solidified and manifests itself in cold, hard surfaces: Rough, opaque – absorbent. Polished, lustrous – reflective. The installation consists of four square tablets made of Alta quartzite, Larvikite, stainless steel and untreated steel. Collated to one big square, the tablets forms a polypthych where each of them tell their own material story. The space between the tablets forms a negative that separates them from each other and underlines the differences between them. The stringent lines that have been cut with industrial precision, along with the authority, density and monotonous impact of the work, create a monumentality within it.

Central in the works of Terje Roalkvam (b.1948) are the contrasts, but also the dialogue: between forms, between materials and between underlying stories. Materials made by the human hand are assembled together with the creations by nature, and within this interaction, Roalkvam is investigating the most basic elements of visual arts. Tablets (square) has thus strong ties to the history of art. Meanwhile, it is also tempting to draw associative lines from the work, its title and placing in the entrance hall at Department of Education, back to the prehistoric, inscribed tablets and all the way forward to the modern innovation within material technology. The minimalistic form of imagery in Tablets (square) substantiate a superficial material boundary, but at the same time this materiality creates a depth – a room for interpretation.

Stine Lundblad, art historian, executive officer, Tromsø Museum – universitetsmuseet

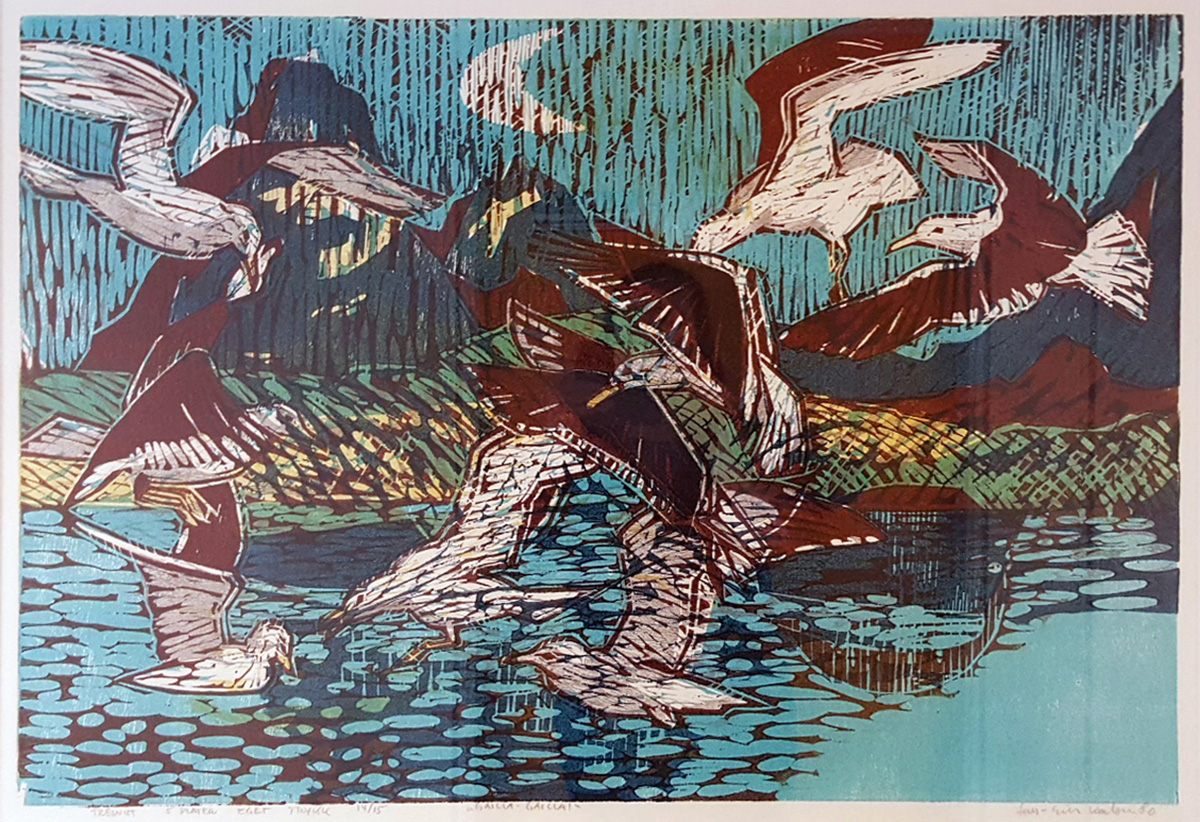

Lars Eirik Karlsen often combines the dramatic landscape of Lofoten with severalt types of sea birds in his pictures. First, his compositions are drawn on paper, then they are transferred to the wooden boards on which the motifs are cut – one board for each color. The technique invites to simplification, in colour as well as form. Karlsen strives for making his woodcuts function on two levels – from a distance as a figurative composition of visual patterns in strong colours. At close range, in the derails, he attemts to give the pictures a more abstract character.

As a contribution to the debates regarding existence and protection of birds along the Norwegian coast, Karlsen has drawn, cut and painted different species of sea birds since the 1970s. He is particularly known for his Atlantic puffin motifs, but he has also “portrayed” other coastal species, such as northern gannets, sea ducks, razorbills, seagulls, cod and killer whales.

The current picture displays three seagulls fighting on fish entrails, thrown to the sea by the artist himself, after a successful catch on the Hadsel fjord. The title of the picture refers to the scream of the sea gull. Karlsen (1948–) lives in Svolvær in Lofoten. He is educated at Statens Håndverks- og Kunstindustriskole. His main technique has been colour wood cuts. He has partaken in numerous exhibitions with other artists and has had several solo shows in Norway as well as abroad since his debut in 1975.

Per Posti, art historian, Tromsø

Under the surface is part of a series of under water-photographs by Heidi Wexelsen Goksøyr, executed during the period 1991–2001. The pictures were made in the Mediterranean Sea, and the models were local children. The colours vary between light blue and white. The pictures were shown as transparents or c-prints at exhibitions in several Norwegian and Danish galleries. Many were bought for public decoration in Norway as well as abroad. The artist writes at her home page that there is something seducing with water, because there one is beyond our own existence, in a kind of magical, introvert, meditative and weightless world. This is also appropriate to the picture in Tromsø. Two girls dressed in white dresses are swimming between the sand covered bottom and the surface of the sea. Playfully one of them is grabbing the foot of the other. The composition is harmonious, without stiffening. In its centre, the girls are reflecting each other as in couple dancing. The one to the left is drawn away from the abyss indicated by the slightly sloping sea bottom. The air bubbles near the surface tell us about buoyancy. In addition to being a beautiful, the picture can be understood as a homage to the vitality of children’s playfulness.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

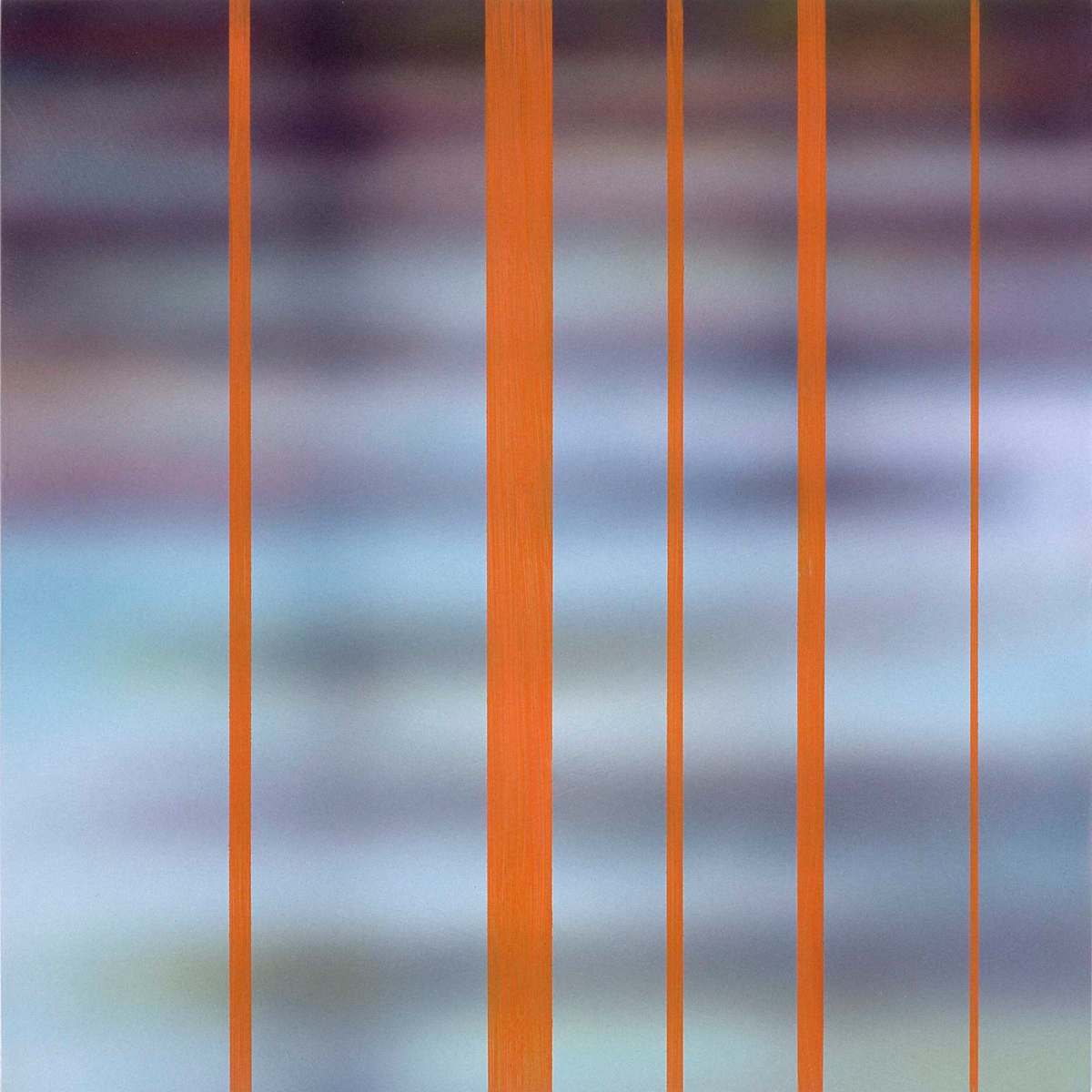

Seasons (polym. Cadmium orange) is part of a series of fifteen paintings decorating the "Silent room" at Teorifagbygget, a non-denominational arena for contemplation. The paining hangs on the wall together with two of the other fourteen paintings – the rest hangs inside the room. Harald Fenn (b. 1963) contributed to the revitalization of the painting as such in the early 1990s. Typically, his paintings consists of two layers, one, an abstract, more or less wiped out landscape, the other, several sharp edged and vertical coloured lines overlapping the landscape. Variations of the landscape as well as the colour and breadth of the lines indicate changes of the seasons and the day and night. Seasons consists of a partly brown and light blue landscape, overlapped by five vertical, orange straight lines of diverse width. The painting is in a refractive field between landscape painting and non-figuration, nature and manufactured culture. The stripes have been characterised as a grid between the viewer and the painting. The painting makes it possible to linger on the shady landscape beyond the grid, as one could reach a higher level of reality by looking at devotional images in medieval churches. The abstract character of Seasons makes it appropriate as an arena of reflection for users from diverse religions and life stances.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

Ever since his debut in Kunstnerforbundet (The artist association) in Oslo in 1977, Leonard Rickhard has combined different kinds of visual representation in his paintings. Added to a simplified, realistic pictorial language, we can see diagrams, shapes reminiscent of blueprints, wiring diagrams and pure colour fields. A starting point in many of Rickhards pictures have often been related to stories and pictures from WW2.

A story can be suggested about the barrack-like, simple buildings and figures in Analytic picture – by the coast. The repetition of the house in the right part of the picture, and the distance between the two houses as well as the figure appearing in the doorway are indicating a narrative. We can see both exterior and interior, and the house to the left looks like an x-ray or a combination of several perspectives and stations in the narrative. At the same time, the unexplained surroundings and anonymous figures contribute to the making of an enigmatic atmosphere – as if we are looking at fragments from an imperfect memory.

Combinations from different sign systems and forms of representation makes it necessary to read the picture in leaps, like a series of picture signs. The displayed and represented utterances are not synthesized and shaped into a coherent unity.

At the upper part of the picture the motif breaks out of the main shape of the painting and its frame. This makes the relation between the motif and frame less obvious. The frame is not a clean and square limitation, like in a traditional painting, but an active part of the picture, as it has added itself into the content.

This break with a conventional form of representation, can be seen as a metaphor of how all paintings, and all kinds of representations involves a way of framing the understanding and presentation of knowledge. In Rickhard’s painting the area where the regurlar shape of the frame is broken is emphesized by an intense red color, it is like a power central distributing energy th the rest of the painting

Svein Ingvoll Pedersen, executive director, Nordnorsk Kunstnersenter

If you are walking along the footpath that constitutes an axis between the administration building and the University Hospital, you can as a viewer let yourself be disturbed or fascinated by a collection of ten completely mainstream street lamps dug into the ground of a mound by the entrance of the Technology Building. Does this appear random or not?

The street lights you have arrived at are Dis-Position (2015), a sculptural installation by the artist duo Lutz-Rainer Muller and Stian Ådlandsvik. The title alludes to being out of position, and the art work actually is, with its street lights mounted in different lengths and angels related to the ground, and that turn on their lights at different times of the day and night. Actually, they have been drawn up from their original sites at the ten largest container ports and airports in the world, all the greatest centers of power, trade and know-how, and moved geographically to Tromsø. They represent their original sites as well as the global, i.e. the world out there. By gathering the street lights and moving them to Tromsø, the artists have created a new place, an "Everywhere place". The art work is visualizing a changing world, geographic as well as economic, where new structures and communication networks are made, and in which the technology disciplines at UiT The arctic university of Norway are taking part. They are contributing to the positioning of Northern Norway. Thus, the title Dis-Position is meaningful.

Helen Kathrine Eriksen, bachelor student in art history and senior advisor at the Centre of career and employment, UiT

If you are looking upwards at Man in Blue Realization from the bottom of the stairs of the Pharmacy Building, there is little doubt that the painting you see displays a man in upright position. Particularly convincing are the contours and lines that constitute the head. The man poses on a black square, while supporting himself on a brown color field. An enigmatic word is written in grey capitals on the surface of the square: "SAKENS" (i.e. the sake's, the subject's, the case's, the issue's, the matter's, etc). Above the man a circular shape is hovering. It is not explicit whether it is a symbolic light bulb, a Halo or the sun, but perhaps that does not matter. In the paintings of Hansen-Krone ambiguous symbolism is common. The posture of the man as well as the distribution of his weight are reminiscent of classical sculpture, and the blue color field on his torso gives associations to a Roman toga, draped around his right shoulder. Almost like a senator or a Catholic saint he points with a charming and a clumsy grace backwards to the roots of academia. The picture is composed of neatly arranged color fields in blue, pink, brown and black. If you are walking closer, it is more abstract. The contours are wiped out and the man's body appears blurred and cloudier. As if a ghost is leaching out of the black square at the lower part of the painting. Does Man in Blue Realization have anything to do with the essence of the matter (Norwegian: SAKENS kjerne)? Or does the ambiguous symbolism of the painting imply something about the intangible character of the truth? Or is the equivocal shape of the figure suggesting something about the duality of body and mind.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

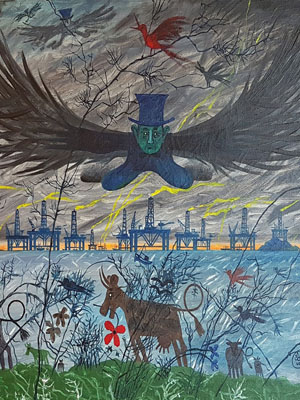

The university's oldest building, Realfagsbygget, houses as its name implies the science education. Rationality, precision and technological advances are often associated with the activities undertaken in this building. Oddvar Torsheim's An overseer can be interpreted as a commentary on modern technology's use and interference in Norwegian nature. With its distinctive, simplistic and imaginative form language, borrowing a lot from surrealism, he shows a view of a landscape with cows, flowers and birds in the foreground. A black naked tree extends to the top of the frame, with branches that appear like a spider’s web or splintered glass. At the top branch sits a red bird with its beak open. In the midst of the rough sea, a boat is struggling towards oil rigs and platforms, located on the horizon. Yellow stripes rise from the platforms and up to the sky, like lightning or poisonous smoke. Torsheim's dichotomical landscape is the arena for various industries, traditional farming and modern oil extraction, all represented under the same threatening sky. A dark figure floats over the landscape, with a wingspan that fills the middle ground. It is followed by several similar characters in the background. The birdman has a bow tie and top hat, an outfit that is traditionally associated with the upper class, while today it is more connected with magicians and magic. In the history of art, the top hat often symbolizes capitalism or supremacy. Torsheim's birdman is ambiguous. Does the red bird warn of a magician casting a spell over the landscape or the government that comes to keep an eye on capitalism's investments?

Hege Olaussen, assistant professor of art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

The three paintings near the entrance of the C-wing of the Science building (Naturfagbygget) are leading us into an abstract mountain landscape. It is only disturbed by two white bars of the wall between the canvases. We are met by rock formations in the foreground of the painting as well as all the way to a snow-covered mountain range in the pictorial background meeting the sky above. Arne Kleng Dahle is known for his abstract landscape paintings, often with an opposing light, and frequently in order to pass on intense atmospheres of nature. An intense luminous effect in the current piece of art indicates that the sunlight is reflected from the snow as well as the stones and the sky. The pictures are divided into several distinct colour fields in different natural colours. Snow covered areas are marked by nuances of white, blue, yellow and grey, while naked rock is market by dark-brown and red-brown fields. The sky is made of nuances of white and blue. The colours are added in different thickness and viscosity; several places the canvas is protruding, and other places the brush strokes are prominent. Occasionally drops of paint has drippled down the canvas. It reminds us that the landscape is a painting, yet It also gives different textures to the hard rocks and wet snow. It is appropriate with a landscape painting in a Science building. The three canvases are reminiscent of the windows through which one can see nature. The format of a triptych is adding a ceremonial character to the painting. Ever since the middle ages, altarpieces have consisted of a middle field flanked by two wings, and in some churches one still can look at the nature through so-called "windows of Trinity ".

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

A glass case by the entrance at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science-building contains objects that captivates the eye and creates a desire to touch. Hard materials, like wood, has taken on the texture of smooth velvet – and rough materials, like branched horns, materialize as sleek and gleaming through the exquisite artistry of Johan Rist.

The items displayed, a large knife, a náhhpi or bowl for milking reindeer, and a guottahat (a bone disc with utensils hanging from leather straps: a smaller knife, a scissor and a nállogoahti or a needle case), are tools for the hand – they accommodate usage in a context of Sami knowledge, at the same time as they are the product of such expertise.

Clever details demonstrate deep practical and material know-how. Like the slit in the sheath for the knife, allowing moist to slip through to prevent the steel from corroding if the blade is wet. Some features might point to regional traditions, for example the sharply bent sheath, occasionally associated with northern Sami knifes, or the meticulously carved ornamental pattern (highlighted with a mix of grease and soot or black-lead to contrast the bright-coloured horn). Moreover, an informed viewer might recall the characteristic clicking sound, sometimes heard when a knife is pressed down into the sheath, a token of a well-executed work, or gauge the size of the náhppi and how it correlates with the relative size of an (imagined) doe herd.

Resting behind sheets of glass, preventing touch and prioritizing the gaze, the art works still mediates different experiences, references and epistemologies. Reminding the bystanders of the multitudes of art-worlds, life-worlds and knowledge systems, both inside and outside of academia.

Johan Rist’s works have been acquired by major institutions in Sápmi. He was born in 1937 in Eanodat (Finland), growing up in Siebe (Norway), he now lives in Lismá (Finland) working as a reindeer herder and a duojár.

Monica Grini (PhD), assistant professor in media- and documentation studies, UiT

The sculpture Hover by Harald Bodøgaard (b. 1958) is centrally placed outside Norges Fiskerihøyskole, Campus Tromsø. The tall sculpture consists of three parts made of steel and granite that are cast and welded together. The formal language is abstract with figurative elements. Its plinth is a rectangular upright construction of steel plates. On its top, the middle section of the sculpture made of red granite is attached in a tilted position. It is carved in a wavelike cylindric shape, and getting thinner towards its top, from which an iron rod is curving further upwards. It is surrounded by three wavelike wings of cast iron stretching out in compass points. The design of the sculpture is put together of classical and more exploring shapes. The conflicting interplay between carved granite and steel adapted by machines is adding an industrial quality to the artwork. The surface is shifting from smooth and sophisticated to raw and unpolished structures. Bodøgaard's art is characterized by high attention to qualities of the materials and by traces from the artistic process. His works are often made of stone combined with steel.

In this interplay an expression of hovering and tenderness is created that appeals to our senses. Bodøgaard had given the sculpture its poetic title Hover, which is indicating change. The upper part is surrounded by an airy lightness as if it is trying to fly away from the lower part that is explicitly heavily anchored to the ground. The sculpture in its open and dynamic shape invites the audience to compose a multitude of meanings.

Eva Skotnes Vikjord, Art director, Art in Northern Norway

Outside of the entrance of The Academy of Music, UiT, a slender and circular shape, almost 7 meters tall, is standing. It is situated on a small plinth and is surrounded by four discrete stairways. The name of the sculpture is Column of tunes (No: Tonesøyle) and is cared in a dark and sappy rock named Diabas, a type of Granite. The hard and even surface of the stone is broken by small furrows along the entire sculpture as well as small concave shapes. The title as well as the shape refers to music. This is also emphasised by the locality of the sculpture outside a building that constantly is filled with music. It is natural to think of music while watching the sculpture. Perhaps it is resembling a flute, or a hidden part of a pipe organ. The holes on the surface indicate that music will flow out of the sculpture at any moment, if we just take the time to listen, as if it was an enormous loudspeaker. The shape of the sculpture, the associations to musical instruments an the material it is made of is anchoring the sculpture to the history of music and the history of art, at the same time as the timeless aspects of the expression and material is pointing to the future and opens up for new tunes.

Ann Lisbeth Hemmingsen, art historian, artistic mediator

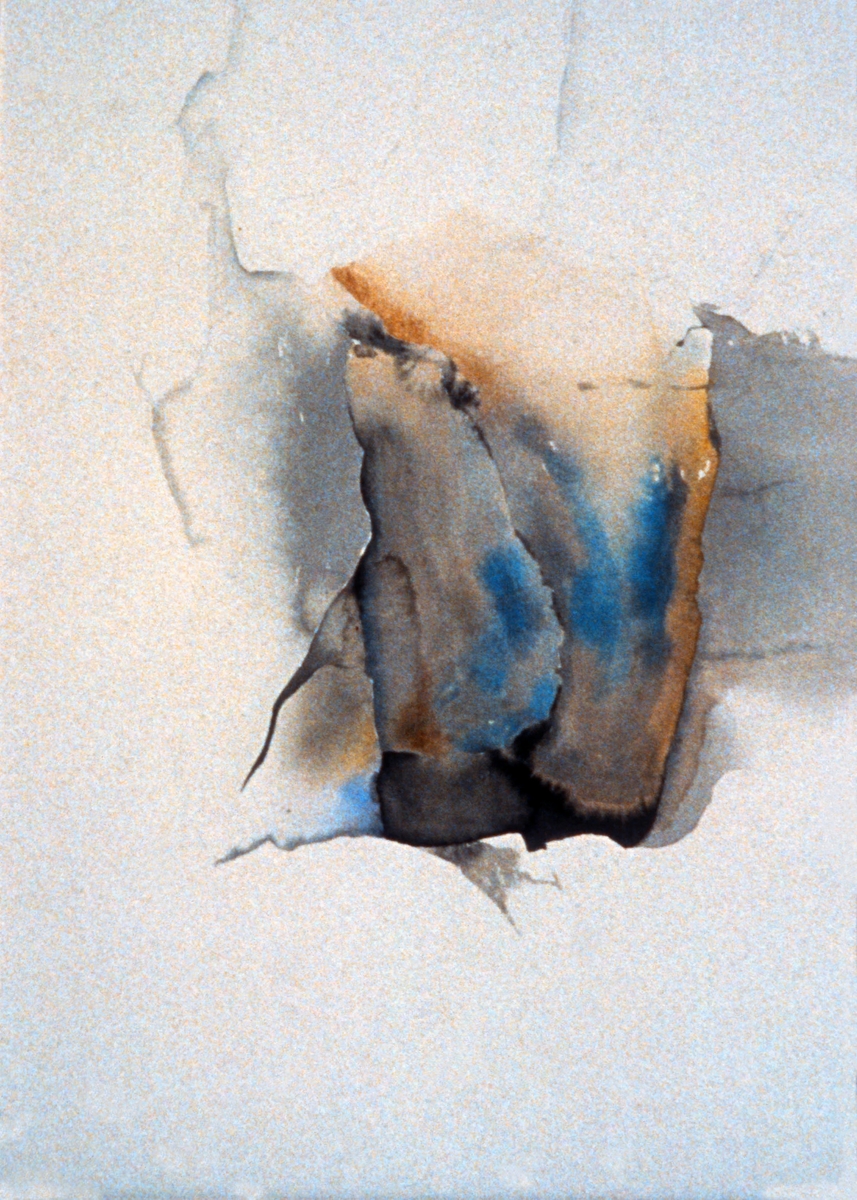

Much of the art of Gro Folkan is dealing with the temporary aspects of life and of the dissolution of the totality. In such a context, Outbreak evokes a notion of perishability, and the sense that the destructive powers of nature are unavoidable parts of life. The formal language of the picture is abstract, including organic shapes and light translucent colors, more concentrated in the center then the periphery of the picture. A Shallow plane is surrounding a fragment that is released in hues of blue, green and brown. The water color is hanging on the wall in a well staircase in the Natural Science building. In such a building it is appropriate with art works that refer to ice, glaciers and the Arctic.

Just as much as the title can be read in line with a principle of perishability, the protrusion of the fragment in the picture is a reference to the climate change. Global warming is melting the polar ice, from which icebergs break loose into the sea. The following rise of the global sea level leads to large scale devastations affecting not only human conditions, but also the food chain and the existence of endangered species, such as polar bears, seals and walruses. This can be regarded as a dissolution of the totality of our existence, which also is a central theme in the art of Gro Folkan.

Trude Olsen, Art historian and archivist, Ministry of Transport and Communications

For the last thirty years, thousands of students and employees have passed Our Sense of Honour and Our Authority, the art work on the southern wall in the central hall of the HSL-faculty. Many of us recognize the two porcelain reliefs by the ceramist Yngvild Fagerheim as both familiar and cherished landmarks at the university. Perhaps it is less known that the two reliefs are parts of a larger work also comprising integrated ceramic works as well as the pattern floor tiles of the hall.

The titles of the two works are not arbitrary. They are drawn from the poem Norwegian sailor song (Norsk sjømandssang) by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson that is dealing with the increasing wealth in Norway, and the play Our Sense of Honour and Our Authority (Vår ære og vår makt) by Nordal Grieg, problematizing the so-called "age of working" (jobbetiden) in the 1920s. Just as the "age of working", the age of the yuppies during the 1980s was a period characterised by a sudden economic growth followed by a brutal economic depression.

Our Sense of Honour is an exaggerated figure with a top hat and with a cigar in his mouth. He is smiling confidently while holding several playing cards with the logo of the old Norol (the present-day Equinor) in one of his hands, and missiles and smoking factory chimneys in the other, and with the Norwegian flag indifferently draped over his arm. The swollen figure is hoovering out of the tower of an offshore drilling rig. It is a caricature dealing with capitalism and the unscrupulous search for profit from the oil industry.

Our Sense of Honour is reminding us of the years when the University of Tromsø was labelled The red university, and the art still was thought as something able to change the world.

Benedikte Elisabeth Lita Ellingsen, Project Manager, The National Museum, Oslo

Red sculpture is located in the waiting area outside the orthodontic clinic in Tannbygget ("The teeth building") on UiT’s campus. In the two waiting areas directly beneath the sculpture there are two similar sculptures (also made by Gjedrem) in blue and green. Since these waiting areas have glass railings, the three works function as a unit, but also separately as individual expressions. According to the artist, the waiting areas appears to be floating in the air, and he has tried to capture this impression in his sculptures. Red Sculpture is a red artifact in the round. Its color makes it stand out from the surrounding green sofas.

Gjedrem is fascination by the sea; this is obvious in Red sculpture, particularly in its wave-like lumps, that make the sculpture look like liquid in a formative process. The artist himself, labels the sculpture as abstract, but its resemblance to liquid and its placement complicates this label. Most people expect sculptures to be relevant to their context. In the case of this particular sculpture, the context of the Tannhuset, where dentists are educated, makes the observer aware of the resemblance of the sculpture to a gigantic bacterium – the organism, in a smaller scale, that dentists have waged war on. Even if this resemblance, as the one to liquid, is not complete, it still challenges the abstract label of the sculpture.

Eirik Gjedrem is an award-winning ceramist with an eye for the abstract. Throughout his career he has won, to name a few, the Norwegian award: “Kunsthåndverkprisen” in 1997, and a merit award in the prestigious “The Fletcher Challenge Ceramic Awards”. Gjedrem is one of few Norwegian artists to practice the press mould technique.

Benjamin Nicolai Berglund, Bachelor student in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

Are you on your way up the stairs from the first to the second floor of the Culture and Social Sciences library, you will see the sculpture Delicacy dog from 1978 by Øyvind Åstein sitting close to a column beside the stairs. The dog looks a bit sad. Perhaps he is waiting in vain for his owner, or perhaps he is just relieving himself.

The piece of art, which is made of polyester, has received much attention from visitors of the library. Especially, it is caressed by children, but it also gets much attention from students, sitting as it does on its own. Åstein is known for his use of humor and irony in his art. So, what is there to say about making a luxury dog like this and calling it a Delicacy dog.

Marit Bull Enger, art historian, advisor, Culture and Social Sciences library

Identidty Landscape

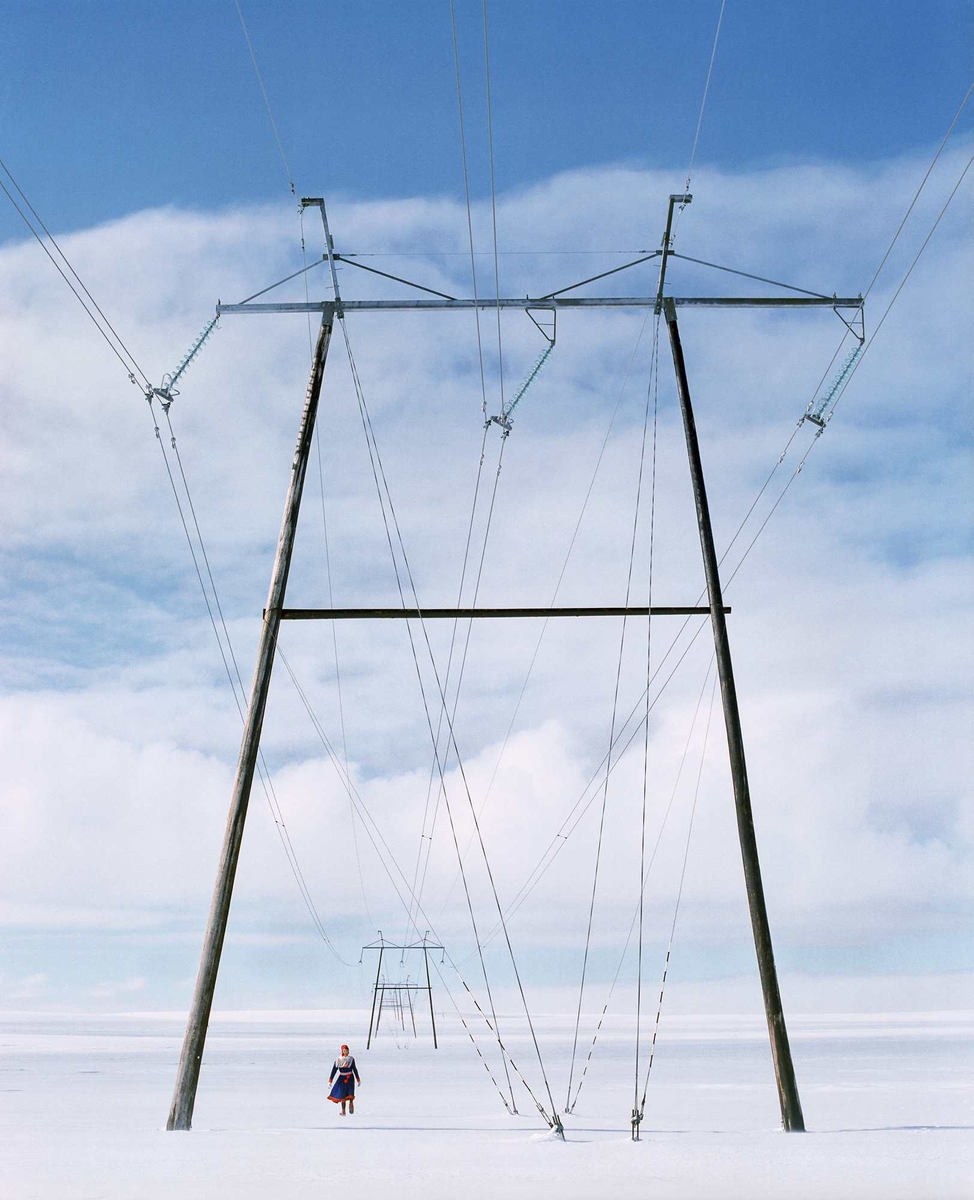

Narratives around identity often involve dualistic tension between different cultures. In a series titled Modern Nomads (2001–03) artist Marja Helander uses photography to explore her dual background, urban life in Helsinki in sharp contrast to Sámi roots in Utsjok, Finland. Helander experiments with her identity by placing herself in various landscapes in the North often in humorous settings. Helander draws inspiration from the Arctic landscape. In the landscapes we find historical references such as ancient monuments.

In Mount Annivaara modern man-made elements, like power lines, contrast with the desolate pristine landscape. Her art presents a subtle, partly humorous reflection around serious issues of modernity and the consequences of human impact on northern landscapes. Helander appears small beneath the massive power mast and appears lost in her traditional Sámi environment. She walks in the landscape, following in the footsteps of her ancestors, but the frame of reference is different.

Helander (b. 1965; Helsinki, Finland) studied painting at The Lahti Institute of Fine Arts, Finland (1988– 92) but chose to focus on photography for her master’s degree at The University of Art and Design in Helsinki, graduating in 1999. Today she also works in moving image in her art. Her work is part of the collections of RiddoDuottarMuseat, The Photographic Museum of Finland, University of Lapland, UiT The Arctic University of Norway/Public Art Norway (KORO) and SpareBank 1 Nord-Norges Art Foundation.

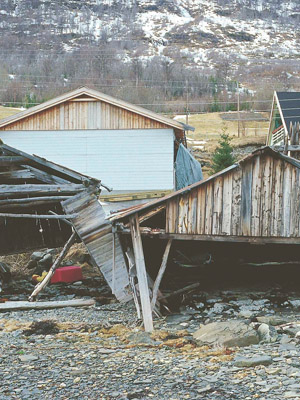

A colour photography displays several buildings by the seashore in Kåfjord, Northern Norway, where the artist lived as a child and adolescent. On the beach there are two boathouses. Further back is a barn, a farmhouse, a caravan and some high-tension wires. The barn and the farmhouse are well kept, but the boathouses display different degrees of decay. A meadow in the background is interrupted by a steep mountainside.

Geir Tore Holm, who has a coastal Sámi background, is interested in tensions between Sámi and Northern Norwegian identities, as well as between nature and culture. The coastal farm at the photo is not displaying any stereotypical Sámi signs, such as the reindeer, the Sámi in his national costume, or the Sámi tent. Yet the farm by the shore of the fjord is a genuine Sámi settlement. Sámi have lived permanently at such sites for centuries. The photo demonstrates conflicts between culture and nature. Buildings, high-tension wires and the meadow are incorporated into the scenery. In the foreground nature is about to take back the landscape, it's only a matter of time before the boathouses are gone. The photo demonstrates the passage of time as effectively as a 16th century still life painting.

Holm has been working with video art, sculpture, photography, performance and installations. He has written as well as lectured about Sámi contemporary art since he completed his education at the Art Academy of Trondeim in 1993. It is relevant to his art that he also is educated as a landscape gardener, and that he is a farmer. He was the project manager responsible for establishing the Art academy of Tromsø. He has received several scholarships and awards, such as the Savio award and the the Norwegian government's guaranteed income for artists.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

A blue-grey bust made of painted concrete is placed on a wooden stand. It is located on the floor of the indigenous room/ Áloálbmotčoakkáldat at the third floor of the Culture and Social Sciences library. The head of a longhaired person is resting in two hands, symmetrically touching the chin with their palms like a collar. The eyes are closed and the facial traits are crudely shaped. The block shaped character of the stone is apparent. The stand consists of a wooden log carried by four bones, lifting the log above the floor. Each of the bones are joined by cones to the log. The log is moderately decorated, among others by a vertical split, in which a tile is positioned in the upper part. Along the bottom edge of the log and on each side of the vertical split, a field, slightly deeper than the rest of the logs surface is carved. The bones of the stand is made of four reused beams. Their surface, grey of age, is interrupted by lighter wood in the kerfs.

The materials of Gaup’s sculptures are often concrete, wood and aluminum. The surfaces are normally simplified. Terms like abstract expressionism and geometric abstraction are used to describe his works. Gaup has been interested in Sámi mythology and epic poetry, which is apparent in his techniques, materials and iconography. Figurative elements like masks and animal symbols are often used. In “Without title” many of these characteristics are evident. The face of the bust is reminiscent of a mask, and the simplified surface of the concrete points at abstract expressionism. The systematic construction and use of materials of the stand display a sensitivity for Sámi traditional handicraft. The closed eyes and mask-like features of the face are leading our attention towards trancelike or dreamlike conditions and death masks.

Gaup (b. 1943) was educated at the art school of Trondheim. His teachers were Karl Johan Flaathe and Siri Aurdal 1973–1978. He was instruone of the founders of the Sámi artist group (The Masi Group) in 1978. He made scenography of the Sámi National Theatre (Beaivváš). His works are bought by among others The Sámi Cultural Council, The Norwegian Cultural Council, The Sami Collections and The Art Museum of Northern Norway.

Literature

Hansen, Hanna Horsberg, Fluktlinjer. Forståelser av samisk samtidskunst. Avhandling levert for graden Philosophia Doctor, August 2010

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

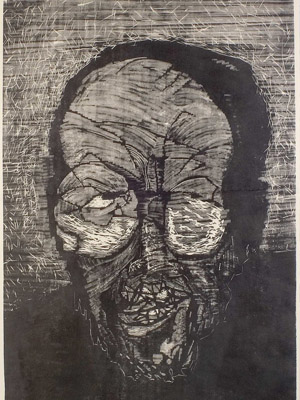

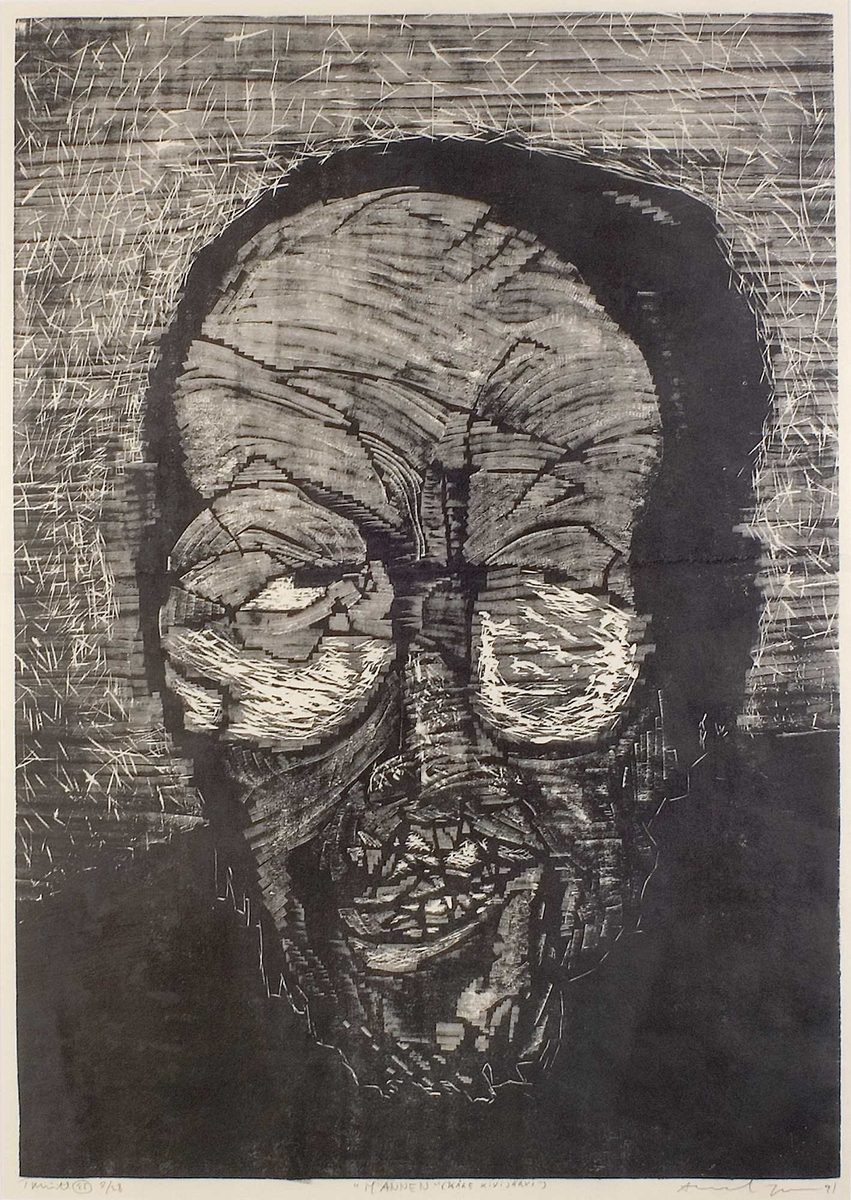

Arnold Jonhansen is one of the few artists who have kept to the medium of printing, despite its declining status in the contemporary art scene over the past thirty years. He has been faithful to this medium and also taken part developing it further. In recent years, he has experimented with photography and developed stencil printing and folding techniques.

Johansen’s pictures concern humans and the landscapes they inhabit, with motifs showing aspects of the coastal culture in Finnmark, his home region in the north. Everyday life and close relations are often points of departure in Johansen’s portraits. They tell stories about desperation and personal crises, but also about strong personalities and individuals who never give up. His portraits place us close to aging and weathered faces that are marked by history, experiences and different life situations. Johansen elevates the theme of portraiture to a universal level by highlighting some of the most fundamental and existential questions about our lives, questions about being human.

In The Man (Kåre Kivijärvi) we see the furrowed, aging face and strong personality of Kåre Kirijärvi (1938–1991). The first artist to exhibit photographs at the Høstutstillingen (autumn exhitition), in Oslo in 1971, Kirijärvi was also the first Norwegian photographer to attain broad recognition as a visual artist. Johansen’s The Man expresses more of Kivijärvi’s personality and temperament than his actual physical appearance. We take note of the figure’s charismatic charm, for example, which is highlighted by an “electric field” consisting of small sparks around his head. In addition, we detect hints of a smile that, together with the partly blurred, serious gaze noticeable behind his crooked glasses, add up to a dynamic expression. Kirjijärvi’s face is full of deep furrows and lines revealing traces of a lived life.

Arnold Johansen (b. 1953) was born in Nordreisa, and is currently living in Tromsø. In 1981 he gratudated from the National Academy of Art (Statens kunstakademi) in Oslo. Already as a student, he distinguished himselves by producing works that combined photography and graphics. Today his works are represented in collections at the National Museum (Nasjonalmuseet) and Northern Norway Art Museum (Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum) among others.

Litterature

Lise Dahl: «Arnold Johansen», i SpareBank1 Nord-Norges kunststiftelse – Utvalgte verker fra samlingen, utstillingskatalog, Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum, Tromsø 2011, s. 78 - 81.

Lise Dahl og Sandra Lorentzen: Inexhaustible Beauty – Uendelig skjønnhet, utstillingskatalog, Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum, Tromsø 2014, s. 24 - 25.

Kristin Løvås, museumslektor, Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum

An eight-meter-high panel of glass is joined by metal screws to the wall close to the stairs in the great hall of the administration building. The hall is covering more than three stories and is crowned by a glass ceiling. A membrane of water is falling from the top of the glass panel to a pool underneath the stairs. Originally the lower level of the hall was furnished as a market. The fountain made a larger unity together with green plants and a canteen. There are tiles of pink marble from Fauske in Nordland in Norway at the edges surrounding the pool as well as on the stairs and the floor of the great hall. The bottom of the pool and the wall behind the glass panel are painted green. The large windows open up to natural light that reflect on the glass panel at different ways as one is passing by.

The piece of art is made of several kinds of materials, glass, water, paint, concrete as well as marble, and is mobilizing several of our senses. It gives an opportunity for meditation and calm to those who make a small stop while passing by, and to those who previously relaxed in the canteen.

There is something limitless about the piece of art. Where does it start and where does it end? Does it end by the pool, or continue on the pink marble in the rest of the room? Is it a sculpture, a painting or part of the architecture? Is it culture or nature? The transparency of the glass panel and its wavy edges translates the natural fall of the water into a man-made language. The Fountain unites the three stories of the hall and relates the hall to the landscape and the sky outside the building.

Zdenka Rusova (b. 1939) moved to Norway from Czechoslovakia in 1970. Her works are mainly graphics and drawings. The figurative language is abstract, usually with references to body parts, horizons, landscapes and dream-like rooms. Often the pictures are poetic and melancholic or in search for some inner truth.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

Ola Enstad, Stimen – på vei mot dypet (The shoal – heading into the depths), made of cast polyester and steel wire, can be found in the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education at the University of Tromsø.

The artwork consists of a shrine of 18 floating, yellowish and glass-like figures. They are mounted on steel wires which is further attached to the wall. Because of the tight steel threads, a diagonal line appears so that the figures together work in a targeted way. The figures have different colour-shades and positions that immediately create movement within the artwork. The artist show us that all the characters together constitute a whole, but that the figures also stands out from each other. The work is placed high on the wall and the figures swim slightly downwards as if they were swimming into the deep. Enstad has used the room in several ways to create depths and contrasts, which in turn can yield more interesting interpretations.

Marion Carstensen Olsen, Bachelorstudent in Art History, University of Tromsø

Jåks’ miniatyrskulptur Liten Háldi er fantasieggende. Det samiske ordet háldi viser til et åndelig vesen, kanskje en skytsånd. Háldi er fremstilt på reise i en båt. Samtidig er skulpturen sterkt abstrahert. Den forteller om et møte mellom to former, mellom en glatt og en ru overflate, mellom to materialer, to farger, to teksturer. Reisen går i konkret forstand over vann eller is – eller den henspiller metaforisk på alt levende. Den virkningsfulle speilingen tilfører andre dimensjoner i møtet mellom fysisk reelle og virtuelle rom. Det er en monumental komposisjon – de små dimensjonene uaktet – en hyllest til kunst, materie, sanselighet, ånd og liv.

Svein Aamold, Professor of Art History, University of Tromsø

Skulpturen God dag (“Moskus”) står i ytterkanten av Campus, i grensesonen mellom fjellbjørk, lyng og ryper og det stramme universitetslandskapet. Steinblokka av larvikitt er tung og organisk og har hode og kropp som skifter etter hvor vi ser den fra. Også den blankpolerte, bølgende overflaten skifter etter forandringer i været og gir oss en daglig status som forsvarer skulpturens tittel. Plassert på en liten høyde ved en av hovedankomstene til campus synes skulpturen som skapt for dette stedet – ja, som noe naturgitt og bestandig. God dag (“Moskus”) ble imidlertid laget for et helt annet sted og formål. Det er den japanske kunstneren Makoto Fujiwara som har hugget og glattpolert steinen, som først ble plassert i kulturlandskap Åkersvika utenfor Hamar i forbindelse med OL i 1994. Ti år senere ble skulpturen flyttet til Tromsø og bidrar her til en campus-identitet i grensesonen mellom natur og kultur, mellom det stedegne og det importerte.

Elin Haugdal, associate Professor of Art History, University of Tromsø

Britta Marakatt-Labbas broderifrise slynger seg elegant langs den buede veggen i Solhallen, der presise sting formidler mangefasetterte scener fra samisk historie, mytologi og hverdagsliv på det 24 meter lange lin-kledet. Både verkets størrelse, detaljrikdom og det tidkrevende arbeidet som ligger bak, er av imponerende skala. Likevel virker verket aldri dominerende. Samisk historie har aldri tatt opp stor plass i de nasjonalstatlige historiefortellingene, slik heller ikke broderiet som kunstform har opptatt stor plass i kunsthistoriebøkene. Maleri, og særlig storskala historiemaleri, har vært i toppen av sjangerhierarkiet det meste av tiden. På lavmælt vis påpeker og utfordrer Marakatt-Labba ulike lag av dominerende strukturer, i et verk som har vært en viktig daglig påminning for mitt eget arbeid som kunsthistoriker ved UiT.

Monica Grini, førstelektor, medie- og dokumentasjonsvitenskap, UiT

Almost at the top of a long flight of stairs, in a busy part of Teorifagbygget, Ida Lorentzen’s painting A dream itself is but a shadow offers the passersby the opportunity to pause, be it physically or mentally, briefly or at length. The depicted interior visualizes time at a standstill and challenges our perception of space. Its vacuity appears both disturbing and calming - what is this room, what is in this room?

Hege Olaussen, assistent professor of art history, University of Tromsø

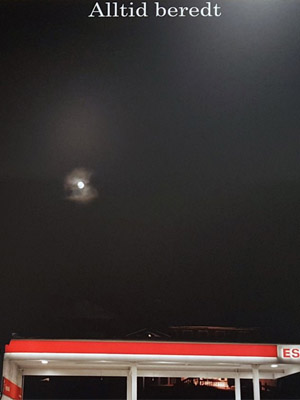

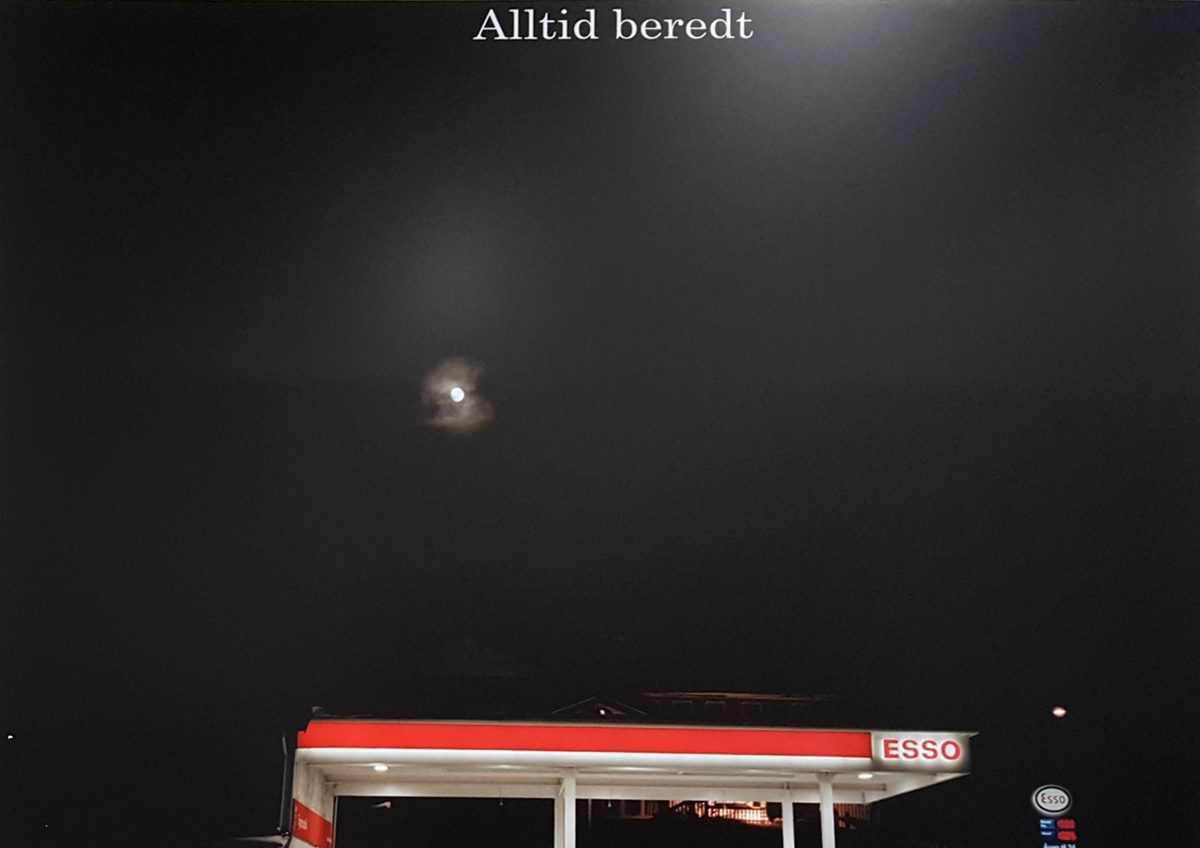

Fotografiene til Kristin Tårnesvik på jusbiblioteket er fra serien Hot spots, 2007. «Alltid beredt» står det på fotografiet av taket på en Esso bensinstasjon. Teksten er speiderbevegelsens hilsen og kan være et hint til speiderbevegelsen som en fremmed, semi-militarisert friluftskultur i Sápmi. Teksten og Esso stasjonen kan forstås som en ironisering over oljeselskapene som til enhver tid vil være beredt til å hente ut det de kan finne profitabelt.

«Hot spots» kan forstås som viktige steder, samtidig som det i 2007 var naturlig å tenke seg at sammenstillingen av bilder fra et subarktisk landskap og adjektivet hot, har med global oppvarming og klimakrise å gjøre.

Fotografienes kontekst, jusbiblioteket på UiT Norges arktiske universitet, gjør at bildene dessuten må ses som kommentarer til debatten omkring rettigheter til ressursene i Sápmi og hvordan dagens profitt og kommers tjener andre interesser enn den samiske urbefolkningen.

Hanna Horsberg Hansen, førsteamanuensis på Kunstakademiet i Tromsø. UiT Norges arktiske universitet.

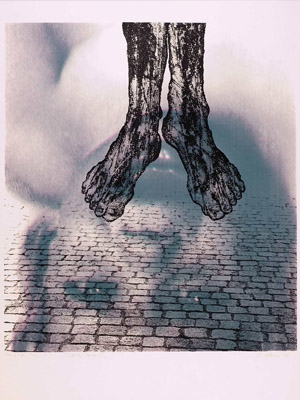

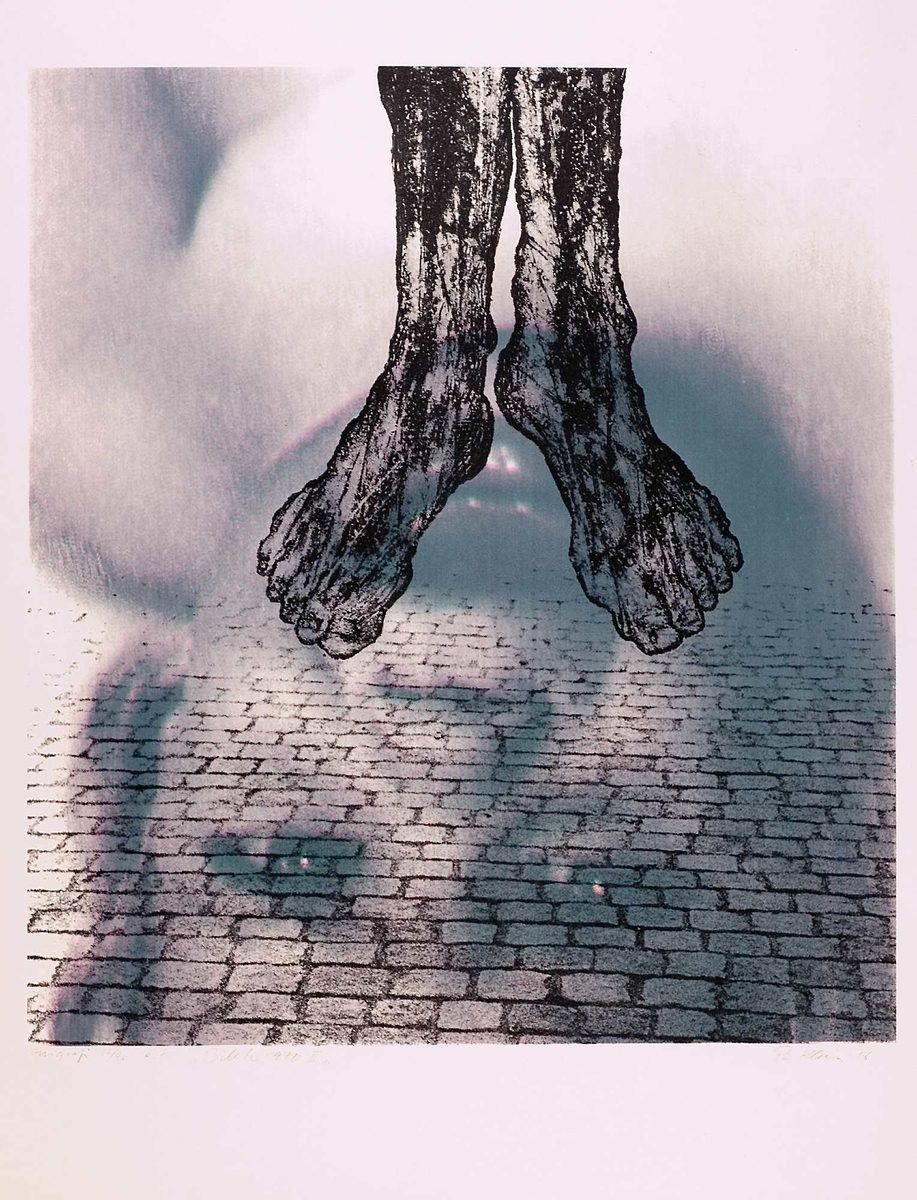

Two naked feet are hanging above a cobbled street. A transparent picture of the face and torso of a child is overlapped by the paving stones. The work of art is a typical silk screening on paper, hanging on the wall at the library of Psychology and Law together with two other silk screenings from the same sequence (Bilete 1976 I and III). Together they make a triptych. All three are combining techniques from graphics and photography. In Bilete II the feet are engraved with nervous lines and the use of rough tools, printed on a double exposed photography - the street and the child. The background motif is repeated in all three works while the main motif in the foreground is changing, a lifeless man and a breastfeeding woman with a child, in addition to the two feet.

The feet, the face of the child and its gaze in Bilete 1976 II are powerful signs of human presence. The street is hard, cold and lifeless. There is something disturbing about the hanging feet and the part of the body we do not see. Are the feet and the child different parts of the same person? Past and presence, stations during the path of life? Is the child a witness or a victim of war? Is it warning us, blaming us or asking for help through its gaze?

Kleiva (1933-2017) was a left wing political activist. During the 1960s he printed posters opposing the Vietnam war. Gradually his art is dealing more with interpersonal relations along with his political commitment.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway.

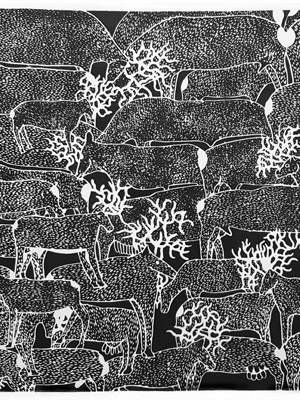

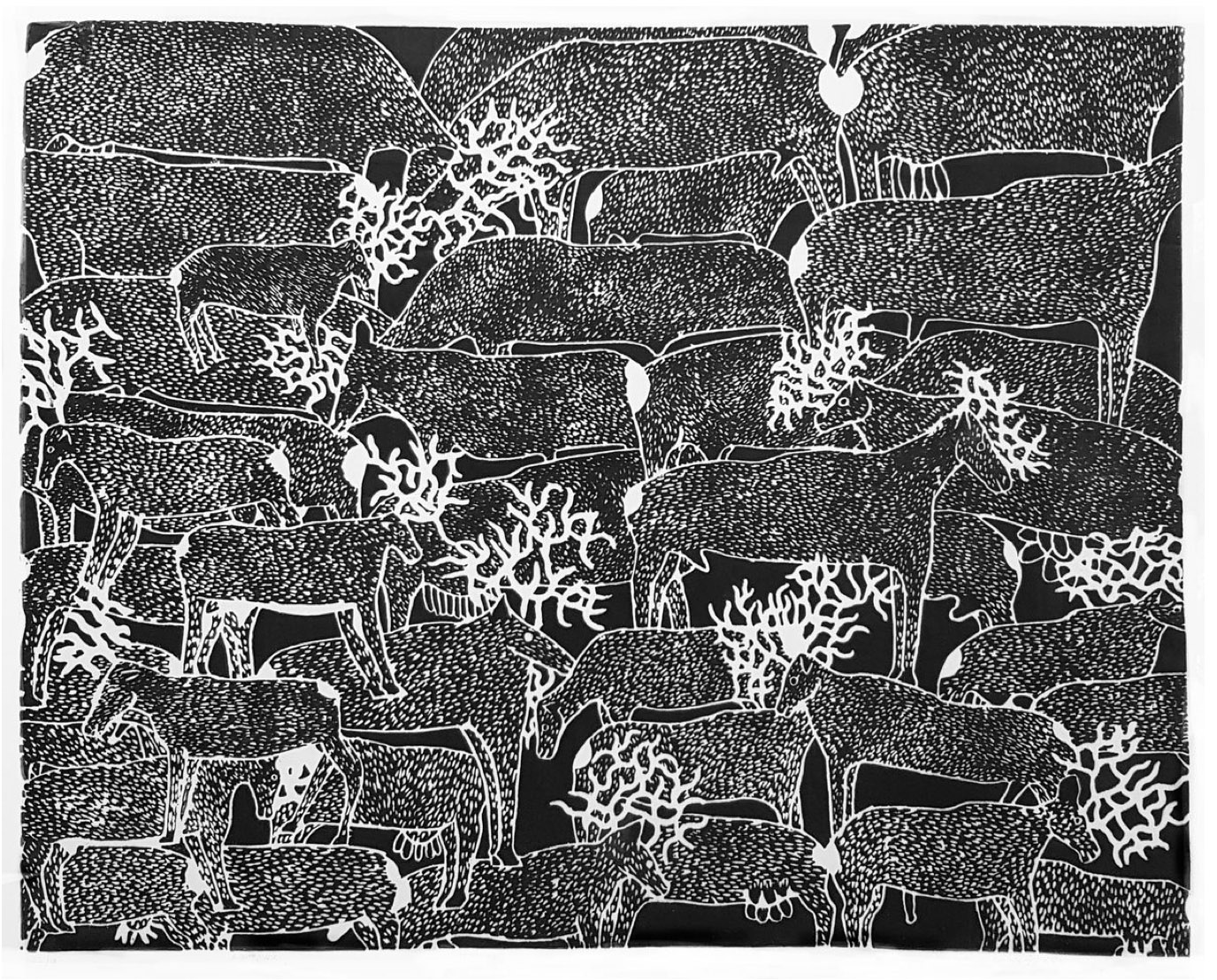

Herleik Kristiansen's (b. 1947) art production includes of a large collection of graphic works with animal motifs. Showing a herd of reindeer in different sizes, Reinflokk is an example of this. Another example is the work hanging next to Reinflokk in room SVHUM A2021, with the descriptive title Fugl, dyr, fisk (bird, animal, fish). Both works are linocuts in black-and-white. In Reinflokk Kristiansen has cut away the white (and partly grey) areas, that is the contour line of the reindeer, the antlers, tails and the many small and closely placed dots, which give the impression of fur on the reindeer's bodies. The areas he did not cut, including the background and the reindeer hoofs, are those that have added colour (black) to the canvas. Visually, the light parts of the image come out. In particular the antlers, whose organic, wavy shapes brings forth associations to a thicket or bush and seem to form its own decorative and stylised pattern on a background of reindeer bodies.

In Reinflokk we see a large gathering of reindeer standing closely together behind and on top of each other in a limited space. Our view is restricted, however, and the composition is cut on all sides (with heads and parts of the reindeer bodies being chopped) and what we see seems to be a part of a larger scene of more animals. This seemingly arbitrary "zooming in" to give a close view of nature in lieu of the more distanced and composed landscape is characteristic of Kristiansen's graphic production. It repeats for example in Fugl, dyr, fisk and the undated linocuts Fugler i Snøstorm (birds in a snow storm), Hettemåker (hooded gulls), Edderkopp (spider) and Humlesurr (bumblebee buzz). The view in these works seems connected to Kristiansen's sensuous relationship to nature. As a child Kristiansen used to look for birds, study their nests (he can still determine the type of bird from its egg), and lay with his body and face against the ground while searching for worms and other insects (Danbolt 2015, 26). Reinflokk may be based on a similar close observation of reindeer. The artist may have seen reindeer during his childhood on the island Tomma in Nesna municipality. Alternatively, he saw reindeer while a youth or adult in Kvæfjord, where he arrived as a new inmate on Trastad Gård, an institution for psychologically disabled youth, at the age of fourteen (Danbolt 2015, 20, 76).

Kristiansen's Reinflokk is an example of so-called outsider art, which is art created by socially marginalised individuals working outside any established art institution (Rossner 2009, 31-32). Today Kristiansen has his own studio at Trastad Design in Harstad, while his collection is on view at Trastad Samlinger. He has exhibited across the world and his works have been acquired by institutions such as the National Museum in Oslo, Art Council Norway and Northern Norway Art Museum in Tromsø (Rossner 2009, 33). UiT The Arctic University of Norway holds three of Kristiansen's linocuts in their collection: Reinflokk, Fugl, dyr, fisk and Pop-Jesus.

Literature

Danbolt, Gunnar. 2015. Outsideren Herleik Kristiansen, Sør-Troms Museum.

Rossner, Simone Romy. 2009. "Outsider Art", Rapport, 5 (October), 30-41.

Ingeborg Høvik, associate professor in art history, ISK, UiT The arctic university of Norway

A black-and-white photograph displays a part of lake Leipimäjärvi in Northern Finland underneath a partly overcast sky. From a viewpoint just above the surface of the lake, among rush and waterlilies, one can see a small, wooded strip of land at the opposite side of the lake where the sky meets the treetops. The sky is reflected on the surface of the lake, that is covered by a crisscross of rush making several cracks in the reflection, as if resembling craquelures of old oil paintings. A narrow, horizontal space is shaped between the clouds and their reflections. A piled cloud in the middle distance accentuates the remoteness of the opposite side. The dark water and the vegetation in the foreground indicate a murky bottom of the lake. There is a play of double meanings, such as sea-sky, reflection-reflected, photograph-painting and reality-dream in the picture. One is led into several spacious spheres gradually replacing each other: sky, land, on the sea, below the sea, bottom, horizon and endlessness.

According to local Sámi tradition Leipimäjärvi is a sáiva lake, meaning a lake with a double bottom. Sáiva mountains were related to sáiva lakes. They were based on the idea of the world of the dead and was inhabited by humans as well as animals. Sacrifices to the sáiva was made upside down; for example, the sacrificial tree was placed with its roots at the top. The relation between the Sámi and his/her sáiva spirit was reciprocal as well as inherited. The spirits were helping during fishing and hunting as well as in other occasions, and the Sámi had to provide with their own life as well as belongings if necessary.

The photograph hangs on the wall in the conference room U-VETT, Teorifagbygget, Building 1, 4th level. It is a part of the project Mytisk landskap (Mythic Landscape), consisting of more than 200 photographs of sacred places in Northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.

Arvid Sveen (b. 1944) is educated as architect, and is working as a visual artist, a photographer and a graphic designer. Some of his works are acquired by Sámiid Vuorká-Dávvirat - De Samiske Samlinger, Nordnorsk kunstmuseum and Kemi art museum.

Rognald Heiseldal Bergesen (Ph.D.), lector in art history, UiT The arctic university of Norway

Guttorm Guttormsgaard’s The Labyrinth extends like a spiral from a small well in its centre to its margins at the university plaza. It is both beautiful and monumental in shape as well as content. Several tonnes of stones are gathered from regional locations such as Senja and Rebbenesøya. Slabs are gathered from Stortorget in Tromsø. They fill the labyrinth. Some are laid out in an arbitrary fashion, but most of them are placed in an elaborate order. The largest and heaviest of the stone formations are made by Guttormsgaard’s fellow artist Annelise Josefsen (b. 1949). It is supposed to give associations to ruptures in mountains, and to serve as a guardian of the Labyrinth.

The project lasted for about four years. With devotion for the northernmost region of Norway, Guttormsgaard was inspired by the people and the landscape of the region as well as the enigmatic stone labyrinths found along the coast of Finnmark. A labyrinth is a part of the ancient Greek epic drama The Iliad, and thus the piece of art also can be read as a part of Western culture. Sámi labyrinths were probably related to funeral ceremonies and can be read as means of transmission from one psychological or spiritual state to another. Some theories explain them as means of protecting Sámi culture from external influence.

In the summer the labyrinth with its flat and open design is approachable for everyone. It is a favourite site for a rest in the sun. Covered in snow in the winter, it is only the well that is visible, lit up in the polar night. A gentle trickling of body temperature water tells us that here is life. At the bottom of the well we can see the starry vault of heaven, with the Milky Way and the star signs in precise order. From archeology to astronomy – a micro cosmos, the endless within the limited, or the small inside of the large, solid as well as floating, and everything in between.

Guttorm Guttormsgaard turns 80 this year. In his home in «Blaker Old Dairy» he has built a life work, an archive of artefacts, art and books. On his Facebook page he writes that "The assortment is personal as well as passionate". He is mostly known as an engraver, but has also worked with other techniques, and has previously executed extensive exhibitions, among others at the universities of Oslo and Bergen as well as at Oslo Spectrum.

Lise Dahl, art historian at Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum

The sculptures group by Gitte Dæhlin is in deed eye-catching through the windows of the the Culture and Social Sciences library when your are passing through the main street of the Campus. And inside of the study hall the tall sculptures are integrated parts of the room.

The work is indicating three time spans – past, present, future – and consists of three parts: two portable life-size figures, each carrying a "column" of glass, and one stationary sculpture. Actually the latter is integrated in one of the sustaining pillars of the of the building. It displays the hands and legs of four persons that are sitting and reading in four different kinds of writings. The persons represent different characters in a north norwegian town: the fisherman in his sweater and boots, the Sámi woman in her ethnic outfit, the businessman-bureaucrat in his grey suit, and the colorful rocky student. One of the individual sculptures shows a mumified/bandaged female figure with mythic feathures that leads our thoughts back to pre-historic times. The other portraits a man burdened with a huge box of glass filled with cricled newspapers. The wornout clothes, the hair and the non-scandinavian appearance might give several assosiations. He is the only figure in motion, thus defining Gitte Dæhlins title of the work: There was – there is – a collumn will arrive.

The two freestanding figures are about 180 cm tall. Their melancolic faces are displaying the kind of expressionism typical of the art of Dæhlin. Today it is obvious that the skulptur group is almost thirty years old. The colour of the clothes has faded, the textiles are scattered with spots and rifts, the newspapers are yellow, eventueally it will all disintegrate. An aspect of perishability has become an obvious part of the work. Dæhlin made these skulptures of reused textiles. They should not be hidden behind montres. The way they are exhibited in the study room of the library, they live and grow old together with the people that use the library.

Helen Nina Sundvall, art historian, lector of visual arts, Breivang videregående skole

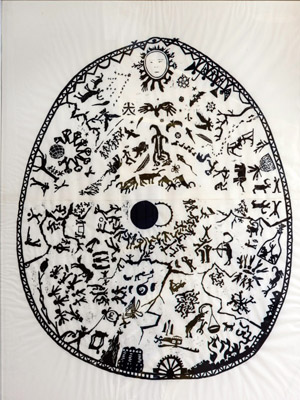

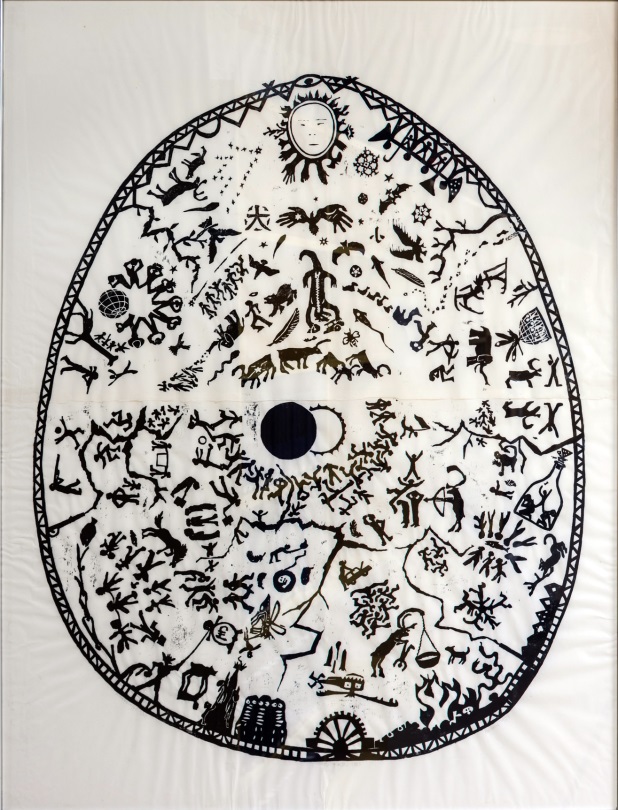

At the indigenous room/Áloálbmotčoakkáldat of the Culture and Social Sciences library the woodcut Ratkin is displayed as the last in a series of four. As a whole the series is based on illustrations of reindeer, but in Ratkin the artist has moved his focus from the reindeer as a concept to the symbolic values of dividing something into different groups. When a reindeer herd is collected, it is divided into groups in order to separate certain animals, e.g. unmarked calves. The picture's motif is inspired by the reindeer herd seen from a bird's-eye view. This is based on the artists experiences with reindeer herding from helicopter. The composition of the picture is shaped like the membrane of a Sámi drum. At first glance you will see a woodcut, the particular shape of the membrane and many black figures against a white background. By a closer study, you will see that the picture is full of symbols representing reindeer, humans, weapons, different animals, birds, plants, a car and a helicopter. The motifs are divided into groups and separated by lines resembling wooden branches.

According to the artist himself, he is fascinated by the separation of reindeer. In Ratkin the roles are shifted and it is the reindeer or other animals that divide humans, and separate good from evil. The motifs show many symbolic constellations that are humoristic as well as sarcastic – and maybe even frightening – a serious topic with an ironic twist.

Hans Ragnar Mathisen/Elle-Hánsa; (b. 1945) is a Sámi painter, graphical artist and writer. He was educated at the State school of art, craft and art industry paint course and the State's school of art, painting and graphic arts. The motifs of his pictures show his commitment to the Sámi people, its myths and legends, and the landscapes of Troms and Finnmark. He characterises his own pictures as naturalistic, but with elements of symbolism and some irony.

Frøydis Henriksen, art historian, lector of visual arts, Breivang videregående skole

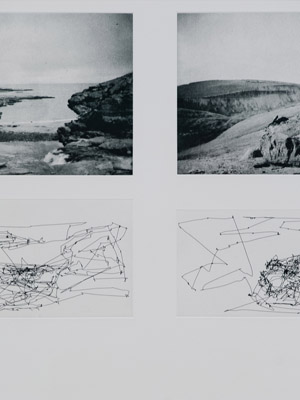

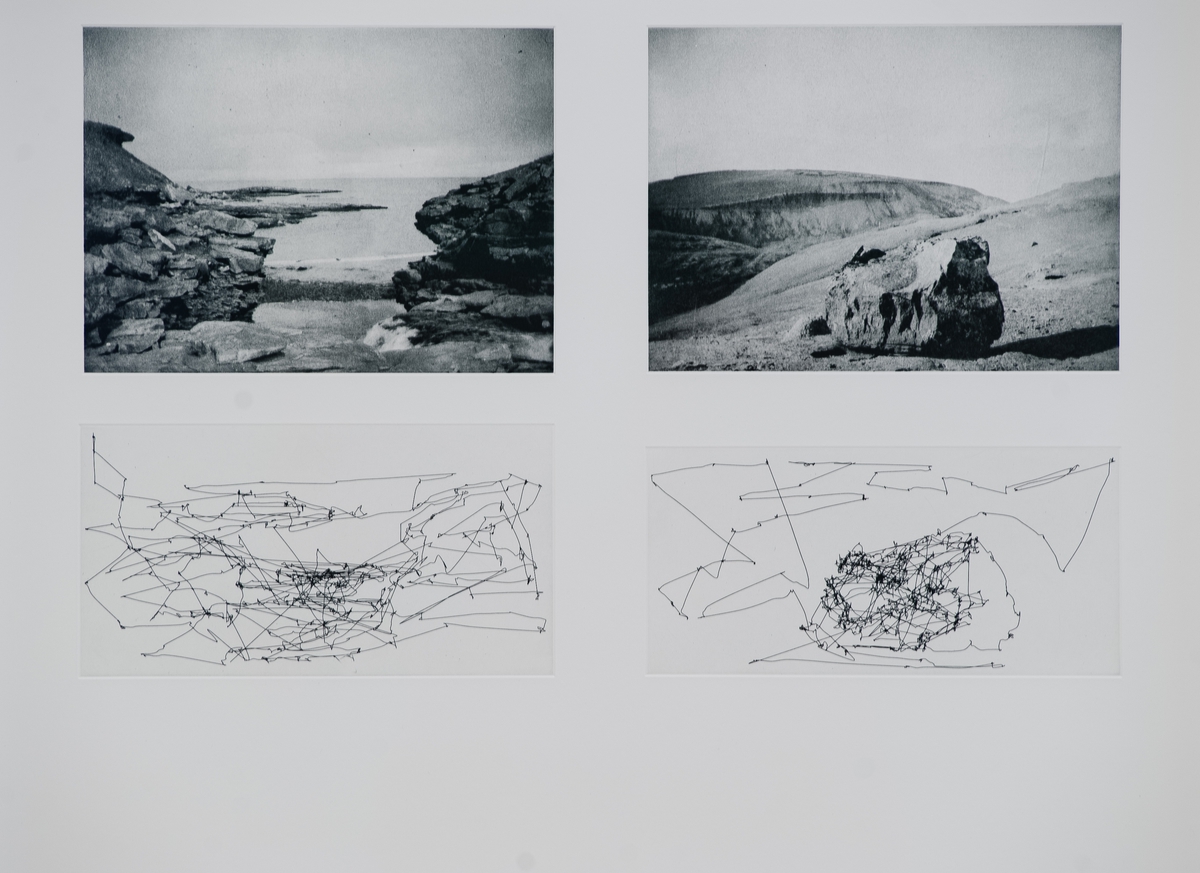

Espen Sommer Eide's Material vision – Silent reading make us reflect on art and science, on senses and technology, and the visible and the invisible. His artwork consists of six pictures (photographs, drawings and graphics), glassed and framed, and a video, which is a documentation of the artistic research, or a kind of filmed performance (the illustration of the current text is one of the six: Material vision – Silent reading 1). The video is made up of several passages, all recorded on Bjørnøya, and it shows the artist's use of an eyetracker that detects the eye's motion on this remote island. Through the video camera and a self-made computer program, the eye's movements are drawn up as lines or dots on the film and in the pictures. Also, a specially crafted tuning fork is connected to the eye tracker and creates sound related to the visual perception of the landscape. The artist makes his perception of the landscape audible and visible. In the first video passage, it is clear that the view follows the heights and valleys of the landscape. The human eye wants to track and measure, it seeks horizons and focus on details. In addition to the recording video, the artist shows a strong control of the visual perception on the landscape. In one passage he moves his gaze down the mountain side as if a book with clearly defined margins. In other passages he shows how the view refines and delineates. And when a bird suddenly flies past, we follow the movement on pure impulse, while the artist holds his concentrated look, like a researcher. The last picture in this installation, Material vision 6, seems independent in relation to the video and to Bjørnøya. In the background of the picture there is a text page, and on top of this is the concentrated eyetracker lines that hides everything except the last text line, which for the insiders refers to the philosopher and phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty's unfinished manuscript published after his death. In English translation it is: "The Visible and the Invisible. The Intertwining - the Chiasm". Giving up his project of writing a book on truth at the end of his life, the philosopher instead worked on a book on the visible and the invisible. The relationship between visibility, sensation and truth is a strong tension in Espen Sommer Eide's art at the Science Building.

Elin Haugdal, associate Professor of Art History, University of Tromsø

For most people driving under this footbridge across the road between the MH-building and UNN, it's probably not that easy to perceive that it's at all a work of art they see above them.

In his work as a graphic artist, Skedsmo (born 1950) often used gradations of geometric shapes - shades of the same color beside each other give the impression of light and shadow and the surface gives us an impression of three-dimensionality and depth. The motives are often geometric shapes and figures, some very simple, others with a complexity reminiscent of Escher's impossible constructions, or highly abstracted expressions. The reverberation from his background as a design student at Westerdahl's advertising school in the early 1970s is clear. The artistic tools are relatively simple and the strength of the image rests on a strict composition.

Skedsmo has taken this style of expression into the construction of the facade decoration in the footbridge between the medicine faculty building and the hospital. Basically, there are only two tints in the bricks that are used to break up the facade, with red and yellow, respectively, as dominant primer colors.

The shapes can remind of the pointed zigzag pattern often used when splicing woodwork. The reddish surface has originated from the MH building, and the yellow from the hospital. The work can thus be read as a clear symbolic expression of how research / education and practical application of knowledge are joined to form a sustainable whole.

Jan Martin Berg, art historian, manager Galleri Svalbard