Rectors

UiT

Finnmark University College

Harstad University College

Narvik University College

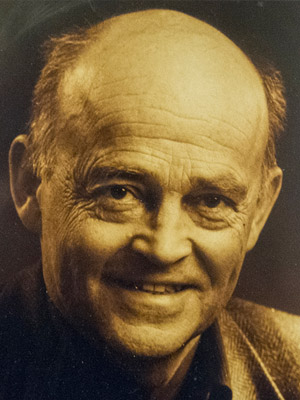

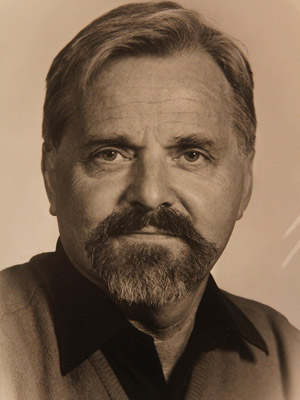

Peter Fredrik Hjort’s name is strongly associated with the establishment of the University of Tromsø and he is seen as the greatest pioneer behind its creation. He was born on March 23rd, 1924, in Oslo (which was called Kristiania at that time) and during the 1950’s he became a medical doctor specializing in internal medicine. Hjort was one of the strongest advocates for a medical program in Northern Norway believing the creation of a university in Tromsø was paramount for the further development of the region. Hjort’s passion for community medicine became central to his work with the university. During the 1960’s, he was one of the few within academia in Oslo who were positive to the idea of a university in the northern city.

In January 1969, he became chairman of the interim board that would lead the process towards the creation of a university. When he accepted the position, he undertook what seemed to be an impossible task. First and foremost, Hjort believed that the costs associated with the establishment of a university were highly underestimated and that the Government would have to support the project although the university would be much more expensive to build than first anticipated. Thereafter, the university, and particularly its medical program, became a highly contested matter as the health bureaucracy and medical community were strongly opposed to its creation.

Hjort believed it was a matter of justice that Tromsø, like the southern cities, would receive its own university. He was elected to the interim board primarily because of his medical qualifications. The medical program was the most complex program to build and also the one likely to cause the most dispute, so it was important that the project was led by a reputable medical doctor. At the same time, the increasing demand for more medical doctors in the region was a determining factor for the creation of a university. Therefore, specialized leadership was crucial. Hjort possessed a keen analytical mind, was politically inclined and was endowed with great social skills. The medical doctor from Oslo led the interim board until he was appointed as the university’s first rector in October 1972, the same year as the university was officially opened.

Hjort only served as rector for approximately one year. When the first election for rector was held in the fall of 1973, he did not receive the support of the entire student body. Hjort pushed back and claimed that he had no desire to remain in his position without the full support of all the groups within the university. He thereby resigned, and Olav Holt became the new rector commencing January 1973. Despite this dramatic end to his rectorate, Hjort continued to lecture for several years at the medical faculty he had worked so hard to establish. Over time there was less political activity and the negativity surrounding his persona diminished. Eventually, Hjort became highly esteemed and was celebrated as a figure crucial to the creation of the university. This was highlighted when Hjort was awarded an honorary doctorate degree in 1982 when the university marked the tenth anniversary of its official opening. Hjort formerly held a position at Rikshospitalet Hospital however he never returned to it after his period in Tromsø. Instead, he continued to do research and worked to further develop and improve the public health service in Norway, primarily through his position at the Norwegian Institute for Public Health. Although Hjort’s major focus was his work within the areas of hematology and geriatrics, community medicine remained an important aspect of his research for which he enjoyed great international recognition. Hjort received several awards and distinctions including being appointed Commander of The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav in 1974 as well as being awarded the Karl Evang Prize for the promotion of public health in 1984.

“The five years I spent in Tromsø was the most exciting and fun period of my life and, at the same time the most productive. There is a time for everything. I believe the groundwork for building the university had to be laid exactly the way it was, although it was primarily the politicians’ idea. If time had dragged out, the university project might have lost its momentum and never come to fruition,” Hjort expressed in an earlier interview with the university. (2008, by Eivind Bråstad Jensen)

UiT arranges an annual seminar in Hjort’s honor to promote the creation of wealth in the northern region.

Hjort passed away peacefully in his sleep at the age of 86 on January 1st, 2011. Although he left Tromsø in the early years of the university, his name will always be associated with the educational institution.

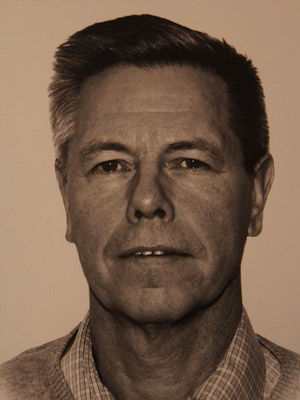

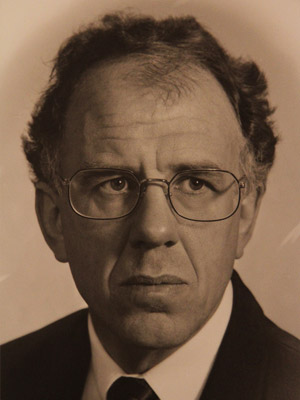

Olav Holt was born in Hedrum in the Vestfold county of Norway on January 7th, 1935. He became a physicist and moved to Tromsø in early 1966.

“My plan was to stay in the city for a year or two. But then there were suddenly plans of a university and we paid close attention to the process of its establishment. When we moved to Tromsø, we never would have believed that we were going to stay for 30 years,” says Holt in an early interview with the university. (2008, E. B. Jensen and M. Hald, Pionerer I Realfag og Teknologi).

Holt was an advocate of a university in Tromsø from the very beginning and did not have to consider long before he accepted an offer to join the interim board in 1969. At that time he was the acting manager at the Northern Lights Observatory. While on the interim board he oversaw the planning of the science programs at the university and has always worked to improve the quality of research and lectures. He believed that the university would not be of benefit to its region unless it was a good, reputable university, that was deemed equal in standard to the other Norwegian universities.

The man from Vestfold specialized in the upper atmosphere and radio waves in the ionosphere. In 1969, he was the first member to receive a tenured appointment at the University of Tromsø and in the fall of 1973, he was elected as the university’s second rector. He commenced those duties on January 1st, 1974.

In an earlier interview with the university, Peter F. Hjort describes Holt as a peaceful person liked by everyone:

“During the five-year period I lived in Tromsø, there was always something going on. There were many fierce debates, and I remember thinking that what the university needed was peacefulness. I felt that Olav Holt was the right person to continue in my position. He was well suited to further develop the university based on the groundwork that was already laid.” (2013, Gamnes and Rasmussen, Fra Fagområdet Medisin til det Helsevitenskapelige Universitet)

Holt expressed that he worked well together with the students when he assumed the position as rector:

“We disagreed on several areas, but we could always trust each other. We communicated well.” (2008, E. B. Jensen and M. Hald)

As soon as the university had become a reality, it received a lot of useful help and support from the other Norwegian universities, according to Holt:

“This was my experience during the rector meetings, the university councils at that time. People have been surprised when I tell them that the rector and director at the University of Oslo, Otto Bastiansen and Olav Trovik, were those who offered me the most support.” (2008, E. B. Jensen and M. Hald)

In 1985, Holt became the director of the university’s research institute FORUT (later NORUT). In an interview from 2008, he expressed that all his hopes and anticipations for the University of Tromsø had come true.

“The university has grown big and keeps high standards. It has a beautiful campus and is a very nice working place for many people. A lot of good research has been done and many good lectures have been offered. The most important is that Northern Norway now has its own reputable multi-disciplinary university.” (2008, E. B. Jensen and M. Hald)

In 2003, Olav Holt was appointed Knight by The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav. Today he is considered one of the pioneers behind the establishment of the university.

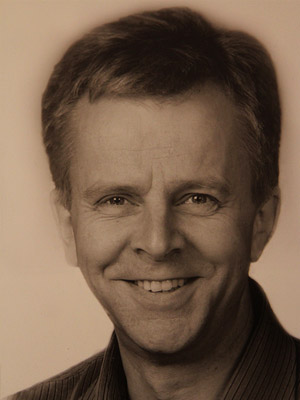

Yngvar Løchen was born in Kristiania on May 31st, 1931. He was Olav Holt’s rival candidate during the university’s first Rector election in 1974 and was the next in line to assume the position in 1977. Thus, a man with a background in humanistic ethics took his seat in the Rector’s office. Løchen was a central character in the first generation of Norwegian sociologists.

Løchen grew up in the upper middle-class in the Oslo-West area and was, from an early age, in opposition to certain aspects of society. His original plan was to become a medical doctor but instead, he chose to study sociology. During the 1960’s, he made several research visits to the USA where he involved himself in the discussion regarding what kind of commitments academics had to the general society. One question remained with Løchen for the rest of his career: How can one develop a sociology and a sociological practice that is relevant to society?

In 1965, Løchen defended his Ph.D. thesis, the book “Ideals and Reality in a Psychiatric Hospital”. His work opened up a whole new field of science; medical sociology.

Løchen was involved in the creation of the University of Tromsø from the very beginning. He believed that the new educational institution could offer the possibility of implementing a much needed reform in the Norwegian university system. In 1971 Løchen was appointed as a professor of medicine at the University of Tromsø. Prior to that, he held a position as associated professor in the Department of Social Medicine at the University of Oslo. The sociologist was a member of the expert committee for social sciences at the University of Tromsø. This committee agreed to adopt a model that was in accordance with Løche’s view of the role of social science.

He was a member of the interim board and was described as a very pronounced member. As such prior Rector Olav Holt believed that Løchen played a significant role in developing the field of social sciences at the University of Tromsø.

“We disagreed on a number of matters. Yngvar succeeded me as a rector, and to be honest I had my concerns. I admitted that to him later. However, I stand corrected. I could have saved myself the worry because Yngvar became a very good rector. The social scientist Yngvar did not neglect the natural sciences during his service. On the contrary, he showed far more interest than I had first anticipated, for example for developing the computer sciences at the university,” said Holt in an earlier interview with the university. (Eivind B. Jensen, 2008, Pionerer i realfag og teknologi)

Narve Bjørgo, the university’s fifth rector, became close friends with Yngvar Løchen and his wife in the 1970’s in Tromsø.

“They cared for us in a wonderful way, as they did with all newcomers. They had a large house, no children, and the university became their life. I have rarely experienced how an institution is drawn into the private sphere like that, to become such a close part of it. I believe I had a realistic view of his role as an institutional politician, but first and foremost I felt very close to him on an ideological level. Yngvar’s finest personal trait was that he never dismissed anything before he had analyzed it and made his own opinion. Yngvar was always ready to listen to everything. That trait also became a weakness in his role as a rector,” said Bjørge in the book “The University Pioneers” (by Eivind Bråstad Jensen, 2008)

Løchen was chairman of the Main Committee for Norwegian Research from 1974 to 1977 and on the Board for Social Scientific Research from 1985-1989. He was the brother of the moviemaker Erik Løchen.

Yngvar Løchen suffered from cancer during his last years and passed away on July 28th, 1998, in Tromsø.

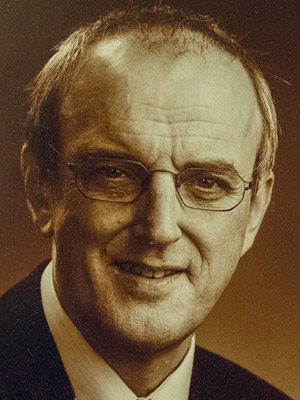

The university’s fourth rector, as well, was from the eastern part of Norway, Oslo, to be specific. Helge Stalsberg was born in Oslo on October 7th, 1932. He studied to be a medical doctor and became a professor of morphology at the University of Tromsø in 1972.

In an interview with the university in 2008, Stalsberg said that he wanted to get away from Oslo and that that was one of the reasons for why he moved to Tromsø.

“It was all the traffic in Oslo. It was the experience I had on a ski trip in the forest surrounding Oslo, the freshly fallen snow was supposed to be beautiful and white, but it was definitely grey. Those were some of the determining factors for why I moved.” (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen, Fra fagområdet medisin til det helsevitenskapelige fakultet).

There were also other reasons why Stalsberg found his way to Tromsø. He was head-hunted for the new university along with five other graduates from his class. Stalsberg was excited about the new model for medical studies that was being implemented in Tromsø and felt ready to assume a top position. Stalsberg was flown to Tromsø in June 1972 as part of a group of 20 people who were all going to work in the university’s medical program. The first evening they all met at Peder F. Hjort’s home and that fall the university had its official opening.

Stalsberg was first a member of the interim board and later, in 1974, he joined the first regular university board. The same year he was elected as a vice-rector with Olav Holt as rector. In 1981, he assumed the position as rector.

Stalsberg described the earliest students as intensely engaged.

“It was a pretty radical student environment. For us who lectured, it was quite demanding, but not only in a negative way. The students were very critical to the whole enterprise, they were clever and well trained. Later, when I served as rector, I would often miss the strong engagement that had characterized the first students.” (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen)

Northern Norway was the region that underwent the most damage during the Second World War. One of Stortinget’s (The Norwegian National Assembly) most important reasons for building a university in Tromsø was to lift the region culturally and financially, and Stalsberg felt very motivated by the thought of supporting Northern Norway after the war.

“It was a national task. We thought Stortinget’s enactment was great and that it showed commitment.” (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen)

Before Stalsberg assumed his position as rector, he felt that radical left-wing perspectives had dominated the university a little too much.

“I registered that there was only a slight increase in the national budgets. The superior authorities wanted new working places in the region to be first and foremost in the private sector. This motivated me to help the university take on the challenge and support the region’s private industry and commerce. I was very involved in the struggle to create the university’s program for business and economics.”

Stalsberg found the period when he served as rector to be both exciting and rewarding.

“It involved working in a way I was not used to. As rector, I could focus on the political tasks. I could devote myself to the future development of the university, and I worked closely with local and regional politicians.”

Stalsberg later worked as a chief physician at the anatomic pathology laboratory at the regional hospital in Tromsø, the present University Hospital of Northern Norway (UNN). He has also worked as a consultant for the World Health Organization (WHO) in the field of breast cancer.

Narve Bjørgo was born on May 3rd, 1936, in Meland in the Hordaland county of Norway and it is safe to say that he is one of the pioneers behind the University of Tromsø. He is a medieval historian and achieved his degree at the University of Bergen.

“It was primarily an advancement in my academic career that drew me to Tromsø. Another important reason was that I had family in Kautokeino that I visited regularly. That is where I got my first “Northern Norwegian” experience. My family and I were very happy in Tromsø,” says Bjørgo in an interview with the university in 2008. (Universitetspionerene, Eivind Bråstad Jensen).

In November 1972, the same year as the University of Tromsø was officially opened, Bjørgo was hired as a Professor of Ancient History. He quickly involved himself in the university politics and served as a dean the Department of Social Sciences (ISV) from 1984 to 1985.

“When I look back on my life, my great dilemma in Tromsø was being torn between a political and an academic career at the university. You can’t fully have both. In my case, it ended up being mostly a political career, and that is also what I continued doing later. All in all, this was a very meaningful part of my experience in Tromsø,” says Bjørgo in the interview from 2008.

In 1985, the man from Hordaland assumed the position as rector with the aim of strengthening the university’s profile in art and cultural history.

“It was important to me that the university could offer a balanced variety of programs. Subjects of art and cultural history were not strongly represented when the university was established, but I believed that they had a relevant place there. In general, I wanted the university to offer more studies of humanities and fine arts,” explained Bjørgo.

However, at that time, the humanity subjects had not yet risen from their recession that started in the early 1980’s, so Bjørgo could not offer many positions. In 1986, the university decided they wanted to strengthen their department of culture and art and prepared a recommendation on how that might be accomplished, which was well received by the Ministry of Education and Research.

Bjørgo was part of a very small group that built a department of history.

“We were pulled in so many directions by all sorts of people. It was hard to manage everything, and our daily lives were very busy. But we were young and happy, and it was almost intoxicating to be able to move up to Tromsø. I felt we were given an almost limitless amount of responsibility. Our working day became far more interesting compared to what had awaited us if we remained at our original institutions,” he said in the interview from 2008.

Bjørgo stayed in Tromsø until 1990 when he went on a sabbatical to do research in England. When he returned to Norway, he started as the administrative director of the Norwegian Scientific Research Association (NAVF), as it was called at that time. He became a professor at the university in his home region in 1993 and the first chairman of NOKUT (2002 - 2005).

In 2008, the historian retired. The same year he was awarded an honorary doctorate at the University of Tromsø for his great efforts to build the institution. Bjørgo died in March 2025.

Ole Danbolt Mjøs was born on March 8th, 1939, in Bergen and studied to be a medical doctor in his hometown.

The man who would later assume the position as rector at the University of Tromsø was at first skeptical to the creation of a medical program in this city. In the 1960’s, in Bergen, he was a student representative member of a government appointed panel that elucidated the further development of medical study programmes in Norway. The majority of the panel wanted to develop a medical facility in Trondheim. Ensuring that the creation of a high quality institution weighed more heavily than catering to rural politics, Trondheim got priority over Tromsø.

“At that time, I had never been further north than the most northern tip of the Bergen Railway, to put it like that. I had no understanding of how important it was to develop Norway, and especially Northern Norway, and far less, a university. I would only arrive at this realization later,” said Mjøs in an interview with the university in 2008. (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen, Fra fagområdet medisin til det helsevitenskapelige institutt)

He headed north for the first time in 1966, to serve as a military doctor in Lødingen for a period of one year. At an early stage, Mjøs was encouraged to apply for a position at the new University of Tromsø.

“Already before I traveled to America in 1972, Helge Stalsberg asked me if I wanted to attend a meeting with Peter F. Hjort and Hans Prydz to discuss whether I would be interested in moving to Tromsø, even though they were well-aware of my sentiments,” he said in an interview from 2008.

Mjøs arrived at the University of Tromsø in 1974 as an associate lecturer in medical physiology. He quickly established a research group that studied the heart. Mjøs was also involved in substance abuse care and assisted in the creation of a shelter for alcoholics in the southern area of the island. He was an active member of the church and also engaged himself in the local politics.

Mjøs became rector in 1989 with the aim to increase the number of students at the university. He believed that if the student population grew they would see a proportional increase in government funding. During Mjøs’ service, the student enrolment increased from 2,700 to 6,500. That increase laid the foundation for building the Non-experimental Science Building (Teorifagbygget). More new programs, such as peace studies and religious science became available. The university became visible both nationally and internationally and it has been claimed that Mjøs was the best communication manager the university had ever seen.

“It is important to be visible. As I see it, I have contributed the most when cooperating with people who are competent in their field as well as politically. Then I can use my strategizing skills. I have always believed that it is important to work as a team. Because of my background with community service, student politics, local politics, church, and politics in general, I was also interested in the politics of the university.” (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen)

In 1994, Mjøs did something most unusual by hiring the comedian Arthur Arntzen as professor of comedy.

“At that time the university became a university for the people. They realized what it was all about; it was no longer a university for the elite. We needed variety in our courses and we needed to bring competence to the region.”

For Mjøs, it was a great pleasure to be part of the creation of the university.

“It is fantastic to be able to look back at. A new classical university in Northern Norway has been the region’s greatest initiative for rural politics. (2013, Gamnes og Rasmussen)

Mjøs also had a finger in the pie when the Norwegian Polar Institute was moved to Tromsø. From 1998 to 2000, he was chairman of the Committee of Higher Education, the “Mjøs” committee. He led the Norwegian Nobel Committee from 2003 to 2009 and was a member of the Student Peace Prize Committee in 2009 and 2011. On October 1st, 2013, he passed away in his sleep at the age of 74.

Tove Bull was the university's first female rector and is, so far, the only one from Northern Norway. She was born in Alta on October 31st, 1945 and pursued her higher education in Oslo and Trondheim. Without any promise of a job Bull returned to Tromsø in 1973 but was soon hired at Tromsø Teacher’s College, as it was called at that time.

“As much else in life, it was quite random I suppose,” she said in an interview with the university in 2008. (Universitetspionerene, Eivind Bråstad Jensen)

Bull worked at the teacher’s college for 11 years and was very happy there, especially because she later got the opportunity to do research. It resulted in a thesis regarding the relationship between the first reading and writing training and children’s natural spoken language. During this period, she was also actively involved in education and research politics and had many assignments and commitments outside of the university.

In 1984, Bull was hired as an associate lecturer of Nordic languages at the University of Tromsø. In 1990, she became a professor.

She was soon elected to the university board and was vice-rector during the period when Ole D. Mjøs served as rector from 1989 through 1995. In 1996, it was her turn to assume the position as Rector. However, in an interview from 2008, she claims that she never planned to achieve any of these central positions.

“Hand on my heart, I must say that I have never done any strategizing to enhance my career. I have a lot of love for the region and for the university. Without the university, Northern Norway would never have achieved what it has today in terms of finance, industry and competence. I appreciate all the opportunities I have been given and I have enjoyed all the positions I have had. I like doing research, I like to teach, and I even like to administer. So, in this way, I am privileged and very grateful. It has always been a blessing to be able to do so many different things.”

As rector Tove Bull was perceived as being clear and explicit. During her term as rector, funding for the Non-Experimental Science Building, among others, were placed on the Government budget and Stortinget (the National Assembly of Norway) decided that Tromsø would get its own odontology program. The process of all the ensuing merges started while she was rector.

Bull’s research has primarily been focused on the relationship between language and society. Among other things, she has worked on language contact between Norwegian and Sami, Northern Norwegian language, language and gender and the history of language.

From 1980 to 1995, Bull was a member and chairman of the Language Council of Norway. She was an external member of the Sami College board in the 1990’s and from 2003 to 2007. And from 2007 to 2015, she was a full member of the board. She has also been a board member of the University of the Faroe Islands. She is currently a member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, an honorary doctor at the University of Uleåborg in Finland, and has been appointed Commander of The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav.

Bull has written a number of scientific articles and books within her field. The 72-year-old is still working and holds a 50% position as a professor at UiT until the end of this year. She is determined to apply for an Emerita position after that.

“I would like to continue to work in my field. I believe that working is important and healthy. Besides I have a number of projects I would like to finish,” says Bull, who is considered one of the pioneers behind UiT the Arctic University of Norway.

Jarle Aarbakke, from Bergen, was rector at UiT for nearly 11 years when he withdrew from the position in July 2013. At that time he was the longest serving rector of any Norwegian university. Today he is also well known to many as Tromsø’s deputy mayor.

He was born on November 18th, 1942, and graduated as a medical doctor from the University of Oslo/Bergen. Aarbakke came to Tromsø as an associate professor of pharmacology in 1976. The “man from Bergen” settled in well to his new city and career.

“We had a great time. Our experiments went well. We were young men and women in our early 30s, and we got things done quickly without much bureaucratic delay. The atmosphere at the university was positive and optimistic,” says Aarbakke in an interview with the university from 2008. (Fra fagområdet medisin til Det helsevitenskapelige fakultet, Gamnes og Rasmussen).

Aarbakke remembers one experience in particular, that made him “hooked” on Northern Norway:

“It was May 17th, (the Norwegian National Day, ed.) 1976, and instead of watching the children's parade in town, I borrowed a pair of skis and walked up to the top of Tromsdalstind in spectacular weather. I said to myself that this is a wonderful place to be. I have never regretted coming to Tromsø.”

In 1982, Aarbakke started in a combined position of professor in pharmacology at the university and chief physician at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the regional hospital. From the early 1970’s, he conducted research on what is today called personalized medicine, with a focus on cancer drug’s absorption to the body.

He was dean of the Faculty of Medicine from 1989 to 1993, and during this period the annual intake of new students to the medical program grew from 50 to 90. Aarbakke was chairman of two committees that worked towards the creation of the pharmacy program in Tromsø.

Aarbakke won the rector election at the University of Tromsø in the fall of 2001 and started in his position in January 2002.

“I ran for the position with the aim to expand the university, and one of my hopes was to establish a research fund of 100 million NOK. The Government was not very helpful, but in 2007, Trond Mohn donated 100 million NOK to the university. I said we needed more specialized positions and that the university needed to provide the young people, who wanted to stay here, with good programs,” says Aarbakke.

During his leadership, the university expanded into the field of marine biotechnology and the use of marine molecules in diagnostics, technology and therapy.

Aarbakke became an advocate for merging the university and college in Tromsø, and after a long process, the Ministry of Education and Research approved the merger in 2008. During his period as rector, the dream from 1965 of an odontology program was realized. Together with Vice Rector Gerd Bjørhovde, he also managed to establish a public pilot program.

It was important for Aarbakke to be in close contact with all the groups of the university, and he had weekly meetings with the student representatives.

He was supposed to leave his position on August 1st, 2009, but with the encouragement of the election committee, he ran once again, this time for rector of the merged university. Aarbakke won, and in the following four years, he managed the process of yet another merger. On August 1st, 2013, the university merged with Finnmark College and UiT the Arctic University of Norway, as we know it now, came into being.

Aarbakke has been involved in several government-led research projects. From 1997 to 1998 he managed a public study regarding complementary and alternative medicine (NOU). The committee laid the groundwork for the implementation of new laws and regulations and for further research projects to strengthen the knowledge of this field. This led to the creation of a national research center for complementary and alternative medicine, based at UiT. This center is also responsible for running the Norwegian health authority’s official information website about complementary and alternative medicine. In 2006 Minister of Foreign Affairs Jonas Gahr Støre asked Aarbakke to lead the High North expert committee. The committee laid the groundwork for the Government’s strategic plans regarding Norway’s northern areas, such as the Fram Centre, Barents Watch, the new building for programs of science and technology at UiT, and the icebreaker research vessel Kronprins Haakon.

“I used my position for all its worth to ensure MH-II, the new building for medicine and health science programs,” says Aarbakke.

Prior to the municipal elections in 2015, Aarbakke was invited by the Norwegian Labor Party to join the elections. He ran as their mayoral candidate and won, receiving the highest vote. He served as mayor from October 15th, 2015 to July 1st, 2016.

In 2013, the Northern Norway “hooked” man from Bergen was appointed Knight 1st class of The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav for his contributions towards research and education in the north. Today the 75-year-old is still an active politician in the local community and is professor emeritus at the university.

Anne Husebekk is UiT’s second female rector. She was born in Oslo on December 15th, 1955, but has lived most of her life in Northern Norway.

“The north is where I feel at home. This is where my heart belongs. Today, I no longer feel like an “easterner”, I am even completely unable to change back to my original dialect,” says Husebekk and smiles.

She arrived in Tromsø as a 19-year-old to study medicine and she is the only rector who has undertaken all her studies at UiT and been associated with the organization throughout her entire career.

“I came back to Northern Norway after my residency training in Volda. We were completely decided; My husband and I were going to stay in the northern region for the rest of our professional lives,” tells Husebekk.

She became a fellow researcher of immunology at the Department of Medical Biology in 1984. After that she started working at Tromsø Regional Hospital, today called UNN, specializing in immunology and transfusiology. Since 2002, she has been a professor in that field. Her research has focused particularly on low platelet count in fetuses and newborns (Fetal and Neonatal thrombocytopenia). Two research years in the USA early in Husebekk’s career during the 1990’s made deep impressions on her.

“My research group in the USA was fantastic. The project we were doing during my first visit was very exciting and became the direct cause of patient transfers from Northern Norway to Washington DC at that time. Patients in Northern Norway suffering from bone marrow cancer, who ran out of treatment options in their region, were offered advanced treatments in the USA for many years. These research visits had a great impact on the further development of my career. I brought several methods back to UNN regarding platelets as well as stem cell treatment. I am really proud of that, actually,” she says with a smile.

From 2005 to 2010, Husebekk was research manager at UNN. After that, she had planned on returning to research but instead became vice-dean for research at the Faculty of Health Science. In 2013, Husebekk was asked to join the rector elections. Her rector team won by a large margin and Husebekk assumed the position as rector on August 1st, 2013. She took a leave of absence from her position at the UNN. In the spring of 2017, she joined the elections again, but this time without any rival candidates.

“Jarle Aarbakke was a very strong leader. When I started as rector it was important for me to continue his work for UiT and at the same time find my own style of leading,” explains Husebekk.

How would you describe yourself as a rector?

“I believe I am doing a pretty good job because I receive a lot of positive feedback. Of course, there are some critical voices as well, and I listen to those. I think it is important for a rector to be open and curious. I am genuinely interested in hearing what other people at UiT, as well as outside, have to say. For the university to be noticed and appreciated, it is necessary to create awareness, especially in the capital, regarding who we are, what we do and what we stand for. This job never ends. We have to be on our toes all the time and make it clear that UiT is internationally leading in different areas, like polar research.”

Husebekk is the UiT rector who has witnessed the most merges. On the same day that she entered her new position, the university merged with Finnmark College and, in 2016, Narvik and Harstad Colleges were also incorporated into the organization. During her service, the university has undergone other big changes as well. In the fall of 2016, the university decided to close several courses due to low student enrolment and this summer eight departments were reduced down to six.

“Despite these challenging processes, the university has remained unwavering in its strategy towards 2020, which is to become “the driving force of the High North”. The strategy is an important achievement during my period as rector, and it has given the university board very clear guidelines on how to work. The strategy is good, it gives the university a clear direction and is unlike the earlier strategies. The guidelines force us to rethink the organizational structure of the university,” says Husebekk.

During her service, Husebekk has secured good agreements between the university and the private sector, Tromsø municipality, Norwegian research institutions, as well as institutions abroad (MoU). The 61-year-old claims that she never envisioned herself as rector when she initially commenced her medical studies, but she was very quickly happy in her role.

“I like to manage. My working environment is incredibly exciting. I am much prouder of the organization now than when I was working in the department. I am proud of all our staff members, no matter which level or position they hold. Being rector is not a leisurely job for old ladies, but most of all, it gives me tremendous amounts of energy,” says Husebekk smilingly.

She was appointed Knight of The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav and awarded honorary doctor at New Mexico State University and Northern (Arctic) Federal University in Russia.

Dag Rune Olsen (født 12. februar 1962 i Røros) er en norsk kreftforsker, professor i biomedisinsk fysikk ved Universitetet i Bergen, og tidligere rektor ved Universitetet i Bergen. Fra 1. august 2021 tiltrådte han som (ansatt) rektor ved Universitetet i Tromsø – Norges arktiske universitet.

Associate Professor Lisbeth Halse Ytreberg is originally from Oslo and holds a Master’s degree in English language from the University of Oslo. She worked at Tromsø Teacher’s College before it merged with 3 other colleges. She became the first elected rector of the new institution; Tromsø College. The merger was between the academy of music, the teacher’s college, the college of health sciences and the maritime college. The majority of the employees were opposed to the merger, so an enthusiastic supporter would never have been elected to the position as rector. They probably hoped for a candidate with enough support in the different academic groups, who would make the best of a bad political decision.

“The two first years were difficult and filled with conflict. The colleges were about to undergo extensive administrative changes and the employees were finding their place within a much larger institution. It was demanding,” says Ytreberg.

Partly because the academic environments had very different cultures and partly because the distribution of funding was based on previous results, and the differences in the results were difficult to explain. In time, the funding was distributed more evenly between the different academic branches and the employees resigned themselves to cooperation. Gradually, they could enter a more constructive face.

“Working as a rector was always interesting, but the last period was not just easier, it was also more fulfilling,” explains Halse Ytreberg.

A lot happened on the academic side during the first couple of years. Two groundbreaking achievements are worth mentioning; the work to open an academy of art at the college and the initial work towards a merger with the university. A merger had been discussed in the first years after the University of Tromsø opened, but the plans never came to fruition. Tove Bull initiated a survey called “Friends for life”, which in the year 2000, resulted in a proposal for a merger. In 2009, Tromsø College and the University of Tromsø merged. Today, Halse Ytreberg lives in Oslo and although she has retired, she volunteers at the Red Cross, where she teaches Norwegian to work immigrants.

Jan Håkon Dohmen was originally from Ofoten and became an engineer at the Norwegian Institute of Technology. Towards the end of his period as rector, he was diagnosed with cancer. He showed great enthusiasm for his position as a leader and remained officially in his role until he passed away in 2001.

Edel Storelvmo, who served as vice-rector at Narvik College during this time, describes Dohmen as a reflective and involved person with strong opinions. Already at this point, there were discussions of whether Narvik College should combine forces with Bodø College or the University of Tromsø.

“Dohmen was in favor of a collaboration with the University of Tromsø,” says Edel Storelvmo.

Storelvmo tells that even when she and her husband, Viggo Storelvmo, visited Dohmen on his sickbed, he talked a lot about wanting an alliance with UiT. He kept a “secret drawer” in his office with documents that revealed his many visions and ideas regarding the organization’s future.

“He had a lot of plans that he was never able to realize,” says Storelvmo.

After he passed away, Edel would often have fictitious conversations with Dohmen, especially when she had to make difficult decisions as rector.

He was a very explicit leader and had great ambitions for the college, and I could often anticipate his arguments and opinions during a discussion, she explains.

Towards the end of his career as rector, Dohmen was part of a board that decided on a new strategy where Narvik College would undergo organizational changes for improved interaction within the institution. When Edel resumed the position as rector, she carried through with this work.

Edel Palma Storelvmo is from Sørreisa municipality in Troms county. She holds a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Trondheim. Storelvmo served as vice-rector during the period when Jan Håkon Dohmen was rector at Narvik College. She assumed the position as rector in a time filled with mourning, as Dohmen was diagnosed with an incurable form of cancer towards the end of his career as rector. Despite his disease, Dohmen remained in his role until his death. In October 2001, Edel stepped in as acting rector and became Narvik College’s first and only female rector. In 2003, Edel was re-elected for another four-year period.

During her period, she continued the work that would lead to a new organizational structure of the college.

“We made some sweeping changes. For example, we created four departments. The advantage of this structure was that each department became a more manageable unit,” says Storelvmo.

As with all processes that lead to change, the female rector experienced resistance. However, most of the employees were positive about the new structure. She believes the change led to a more accessible educational institution.

“As a leader, she thought it was important to arrange staff meetings before and after board meetings so that everyone could bring their suggestions.”

“In my experience, I maintained a healthy communication with staff members and students,” says Storelvmo, who consciously kept an open door to her office.

As the first female rector at Narvik College, she thought it was an advantage to be mentally strong, rather than being a feminist. She believed in the power of a good example.

“I just say; high heels, chin up, finish the race,” says Storelvmo, who has later been the managing director of Futurum AS and NHO (Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise) Nordland, among other things.

Today, Storelvmo is vise-rector at UiT the Arctic University of Norway.

Sveinung Eikeland was born in Bergen and grew up on Stord Island. Since 1985, he has been living in Alta -the city of northern lights. The former rector holds a degree in sociology from the University of Trondheim. In 1985, he received a research position in Alta and in 2011, he was suggested as an external candidate for the rector election at Finnmark College. His experience as head of research at The Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research (NIBR) and as managing director of Norut in Finnmark made him relevant for the position as rector and won him the election.

“The transition from being head of research to being rector was challenging but very interesting,” he explains and adds that the employees experienced him as someone who fulfilled his election promises.

A year after he assumed the position as rector, the discussion of a possible merger with the University of Tromsø started. Eikland, the last rector at Finnmark College, worked hard to make it a reality.

“When I looked at the situation in Northern Norway regarding education and research combined with the Government’s new political strategy for the High North, I believed that a merger was necessary to strengthen our position for funding,” he explains.

Many people believe that Eikland’s efforts were a determining factor when the merge happened in 2013. In many ways, the Government’s strategy for the High North influenced the decisions he made in his last year as rector. The Government’s ambitions for the High North strategy focused on developing the region by strengthening the ties between higher education, research and the development of industry and commerce.

“The new requirements were also linked to education and research in Northern Norway and the specifics of what happened at a college became more important than earlier,” explains Sveinung.

Today, Eikland is vice-rector and responsible for UiT’s contribution to developing the region.

Sonni Olsen was born and raised in Vadsø, in the Finnmark county of Norway. In 1984, she completed her degree in philology at UiT, focusing on English and Nordic languages, with elementary courses in geography. She also holds a degree in practical teacher training. When she was elected as rector at Finnmark College, she had little management experience but had been drawn towards leadership early in her career.

“I gained some managerial experience in my 25 percent position as vice-rector. It gave me a taste of that kind of organizational work, and I liked it,” she says and adds that she possessed a talent for this line of work and wanted to enter into a management position.

Olsen confirms that she genuinely likes people and that she finds it rewarding to facilitate the development of institutions. In 1994, Finnmark Regional College, Finnmark College of Nursing and Alta Teacher’s College merged and became one unified institution; Finnmark College.

“When I assumed the position as rector in the year 2000, the feeling of three separate institutional cultures still remained. It was my aim to create a more uniform college.”

Changing an organizational-culture often means that “the new” will challenge “the old”, and in order for the employees to connect through shared attitudes, values and norms, Olsen arranged joined staff seminars.

“An important part of being a manager in an academic institution is to create engagement from the bottom-up because your employees are the greatest experts. You have to create an environment where they can carry out their tasks in the best way possible,” believes Olsen.

Her two terms as rector were also shaped by the implementation of the Quality Reform, a reform for higher education in Norway enacted by Stortinget (the Norwegian National Assembly) in June 2001. It was introduced in the academic year of 2003/2004. One of the greater challenges they faced was changing to a new degree structure and a nominal length of study, so that Norwegian degrees could be comparable to international ones.

“Many of the earlier degree titles beginning with Candidatus (cand.) were abolished. It required big structural changes and there were greater requirements for the quality of education. We had to change all our systems and plan our programs in a whole new way,” explains Olsen. She believes the new structures and all the work they laid down in order to facilitate them, brought the different cultures closer together and made a more uniform institution.

Today Sonni Olsen is dean of the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education at UiT the Arctic University of Norway.

Ketil Hansen is originally from Harstad but has lived the greater part of his adult life in Finnmark. He holds a degree in business management and before he was elected rector at Finnmark College in 2007, he served as vice-rector and dean.

“I was very involved in the institution and made myself visible. As a candidate, I did not have any specific areas of interest, it was more a general approach to the college,” says Hanssen.

His aim was to develop the institution as a whole, by strengthening the quality of the courses and introducing new master programs. The 2007 financial crises that affected the global financial system would influence the resource management during his period as rector.

“We had to adjust our own budget to be able to implement our plans,” he remembers.

“In the end, we did manage to create new master programs,” he adds.

Hanssen especially remembers his colleagues, whom he became very good friends with.

“I believe you become a humbler person in a position like that. You quickly realize that you can’t bulldoze your way through such a large community. It is important to give way so that others can be happy and thrive as well,” says Hansen.

Improving employee development was one of the causes closest to Ketil’s heart. With great focus on decentralized education, Finnmark College could pride itself with growing student numbers during his service as rector.

Arne Erik Holdø is originally from Stokkmarknes in Hadsel municipality in Nordland county. When he was 20 years old, he flew across the North Sea and commenced his studies in aeronautical engineering at Hatfield Polytechnic, outside of London. After 8 years, he obtained a Ph.D. with a dissertation in fluid dynamics, and later, became a professor at the same university. Having spent more than 20 years of his life in England, he longed back to Northern Norway, and in 2009, he was back in Narvik.

“When the position as rector was advertised, I wanted to apply. In the beginning, it was challenging to give presentations because I had lost so much of my Norwegian. It was a mix of English and Norwegian, explains Holdø,” who remembers that it sorted itself out in time.

During his stay in England, he worked as a faculty manager and gained insight into a non-Norwegian educational institution.

“There are obviously many differences in higher education in Norway and England, but nevertheless, I faced similar challenges when I returned to Norway. All colleges strive for higher student numbers and more applicants to the bachelor- and master programs,” explains Holdø.

Apart from the merger, Holdø put emphasis on strengthening the ties between research and private industry and commerce. To attract more students to Narvik Colleg, Holdø implemented English as the main language of all the master studies.

“It has always been important to me that Northern Norway is able to offer education of high quality. The student numbers increased by more than 50% during this period,” he explains.

When he was rector, the college was accredited with new Ph.D. programs, which initiated many research projects.

Holdø was the last rector at Narvik College. The first round of discussion regarding a possible merger with UiT started as early as 2009.

“In my opinion, it was essential to be a strong institution before merging, so we could hold our ground through the process. I wish we had been even stronger before we merged.”

Nevertheless, Holdø believes that the end result, UiT the Arctic University of Norway, provides great grounds for further development.

Jan Meyer’s background was in special education and he became Harstad College’s first rector in 1990. He was appointed by the College Board of Troms County after an external job announcement. However, the college was considered to be established in 1983, when the social education program opened. Before 1990, the college did not have a rector, only directors of the different areas of education. Harstad College was Norway’s first multidisciplinary college with programs of economics and health science under the same roof.

Jan Meyer had a central role in the entire period from 1983. During his period as rector, he fought hard for the college to remain as an independent institution. The authorities wanted to compress the country’s almost 100 regional colleges into 26 colleges, and thereby join together Narvik and Harstad College. However, those who fought for independence won and both cities managed to keep their own educational institutions.

The other big achievement of his period as rector was ensuring the college had its own building. HiH was originally located at the local shopping mall and was the only college in Northern Norway without its own facilities. When the funding was secured, they discussed whether the location of the new campus should be in the city center or outside. Meyer was in favor of a campus in the city center, and this is where we find the current UiT Harstad.

Pål Markusson grew up in Bjerkvik in the Nordland county of Norway. In 1982, he graduated with a major in social sciences from UiT. He was elected rector at Finnmark College in 1994, after serving as rector at Finnmark Regional College. Finnmark College was the result of the education reform initiated by Government Minister Gudmund Hernes. In Finnmark, it led to the merging of Finnmark Regional College, Finnmark College of Nursing and Alta Teacher’s College. During the first years after the merger, the new institution worked hard to implement the reform. The three institutions were very different. The regional college had ambitions to conduct research and teach classes like a university, while the other two offered a vocational education, with focus on lectures and practice-oriented learning.

“I was an active participant in the discussion regarding the institution's new direction, and in that way, I made myself visible. It was probably an advantage that I had been rector at one of the earlier institutions as well,” he explains.

“It was an exciting period. We spent a lot of time gluing the three institutions together, to make the new institution appear as uniform, from both an inside and outside perspective,” he adds.

The ministry stressed that all higher education should be research-based.

“I came from a tradition where research was central, so it was important to me to incorporate that into the new organization,” tells Markusson.

It was challenging to find a balance between a lecture-based-learning approach and the requirement for more research.

“It led to many heated discussions and we had to work within the limits of our budget. We tried to find a positive balance between research and lectures, to preserve the good qualities of both the vocational colleges and the regional college,” says Markusson.

The result, a unified institution under the name Finnmark College, was a stronger educational institution, with a robust administration in line with the modern, political requirements.

“The Ministry granted us more authority and we were left with greater latitude for strategizing. At the same time, we witnessed a growth in the entire sector, with increasing student numbers, which created many new positions at the college. It was very rewarding to be a manager during a period of such growth,” remembers Markusson.

He explains that the college hired many young candidates who demonstrated great idealism and engagement.

“We succeeded in gluing these institutions together. With three institutions, all wanting to keep their unique features, there was no guarantee we would end up with such a good result,” he says.

Kristian Floer was Harstad College’s first elected rector. He had a background in pedagogy and was encouraged to join the rector-election because of his sociable character and his prior experience as rector.

The first rector-election took a dramatic turn. Floer’s rival candidate, who had received a lot of attention in the media, was first announced as the winner. However, it appeared the election-committee had made a mistake by ignoring the different weight of the votes from the students, academic- and administrative staff. The recount showed that Floer was the actual winner of the election.

Kristian Floer’s period as rector was shaped by the college's relocation. They wrapped up their existence at Kanebogen mall while planning the new college-building by the harbor boardwalk in the city center. Old factory buildings were renovated and restructured to accommodate lecturing rooms and office spaces. In the same year as Floer stepped down from his position, the college would move into its new facilities.

The college had a limited number of students during this period but had a clear strategy to expand by offering more study programs. During Floer’s period as rector, the college opened up a program of child welfare education.

Per Åge Ljunggren is born and raised in Narvik. He has a degree in civil engineering from the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim. After working as vice-rector and dean at Narvik College, he was asked to step in as acting rector in August 2007. The College faced a challenge when the sitting rector stepped down as she was employed as the managing director of NHO (Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise) in Nordland.

“I was asked to take on the role as acting rector and I knew it was only for a limited period. I was actually happier in my old position which involved managing as well as lecturing and advising in production technology,” explains Ljunggren, who has now retired.

When he served as rector, the college faced many financial challenges, and Ljunggren’s aim was just to see the year through.

“I remember that work usually went well, although the period was characterized by discussions regarding the university’s spending. At least the members of the management team worked really well together. That was very helpful.”

Ulf Christensen is a chemical engineer, with additional degrees in pedagogy, and public administration and management. When he assumed the position as rector after Lisbeth Halse Ytreberg at the beginning of the new millennium, he envisioned a college more visible from the outside, therefore, making publicity for the college became a top priority. He established relationships and agreements with both the public and private sector, and developed many political connections, both locally and nationally. He also had many contacts in the media. Christensen was known to be a gifted networker and this benefited the college greatly. The cooperation within the organization was also greatly improved during his period as rector.

The process of merging with the university would define this period. He professed that a merger would have to be based on a process of integration to preserve the good qualities of both the educational institutions. This sentiment received much approval from both the college and university board as well as the top management. In hindsight, it was probably the key ingredient to a successful merging process. The former rector believes that it was a wise move to establish working groups in the most important core areas.

“Being rector at Tromsø College was bot exciting and interesting, but also demanding. The whole process of merging was very hard work,” says Ulf Christensen. Today, he is a senior advisor at the career center of UiT the Arctic University of Norway.

Johansson was contacted by a recruitment company from Bergen, which was appointed to find a candidate for the rector position at Narvik College. The aim was to find someone with a background in technology and experience with management. They landed on Professor Jonsson, who was currently working at a university in Sweden.

“They wanted me to strengthen the solidarity among staff members at the college. I enjoyed my time there, although the difference between being a manager in Norway and Sweden was much greater than I had first anticipated,” he explains.

The challenges of this period were multiple. The discussions revolved around the financial management of the college and the organization’s willingness to cooperate with its staff members and the surrounding environment.

“In my period, we spent a lot of time trying to find solutions to the college’s financial situation. The ministry made some remarks about our financial statement; we had to come up with a better financial strategy and make sure we followed up on it,” says Jonsson.

At this time, the student numbers were too low compared to the variety of programmes the college offered.

“The management and staff members did not show an overwhelming interest in the restructuring and efficiency improvement of the organization,” says Jonsson.

In his opinion, the college was not aiming for any big changes during his short period as rector. However, he refers to an increased level of discussion regarding colleges and universities between May and December 2008.

Olav Daae is a social scientist with a major in pedagogy. When he ran for the rectory, he already had many years of experience at the college, being one of the pioneers from 1983.

He had worked in both of the college’s two departments; the department of social education and the department of business administration and social sciences. This made him a unifying candidate in a period defined by many internal conflicts. He was encouraged to join the election by people from “both camps”.

He lectured courses on business management for several years before he became rector and took on a role as a leader himself. He had always been favorable to the college’s organizational structured of dual leadership, where responsibilities were shared between the rector and the director. However, his experience made him aware of the challenges of this structure and today he prefers a single leadership model.

At the beginning of Daae’s period, the college moved to new facilities. The organization was also struck by the IT-revolution and the working methods changed quickly and radically, which required a lot of effort from everyone. With the relocation, Harstad College became more visible to the city and the region and in time, the institution strengthened its place within academia as well. The college built ties with the colleges in Narvik and Bodø and strengthened its international profile by building relations with universities and other institutions in Northwest Russia.

Ulf Halvorsen trained to be a civil engineer at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim, where he graduated in 1959. In 1966, he obtained a Ph.D. in engineering from Lund University, in Sweden, at the Faculty of Engineering. When Narvik College arranged its first rector-elections, he signed up as a candidate and won the position.

“I ran for the position because it offered me new and exciting challenges, and I believed I possessed the right qualifications,” he says.

And thus, he became the college’s first rector to manage the merger of three educational institutions; Narvik College of Engineering, Narvik College of Civil Engineering, and Narvik College of Nursing.

“It was very demanding,” admits Halvorsen.

The university college reform, initiated by Minister of Education Gudmund Hernes, created many challenges with regards to the working conditions. Joining three different types of study programs together under a single institution would also prove to be difficult.

“The staff members needed time to get the sense of community and belonging,” explains Halvorsen.

“There is always tension within an academic institution, but I believe we succeeded in creating a feeling of solidarity and affinity in the newly established college. I placed a lot of importance on creating a positive social environment within the institution,” he adds.

Bodil Severinsen Olsvik held a master’s degree in pedagogy when she started in her position as manager of the Department of Business Administration and Social Sciences at Harstad College (HiH). Later, she became manager of the Department of Health and Social Care. Before the rector-election in 2011, she had managed both the college’s academic branches and was encouraged to run by colleagues from both the departments.

She describes a “wave of quality” flushing over HiH during her period as rector. It led to new, specific requirements and the college faced great challenges regarding student flow, academic levels, formal competence, publishing points and assignments.

The college prioritized competence development of staff members and set aside significant resources for facilitating academic staff to achieve the level of associate professor and professor.

“All the hard work bore fruits. At the end of my rector period, 70% of our academic staff in the Department of Business Administration and Social Sciences were associate professors or professors,” she explains.

The college also strived to enhance its profile within the region. A letter of intent between Harstad and Narvik College was written and resulted in a Preliminary Course of Engineering and a Bachelor Program of International Emergency as a joint project.

Bodil Severinsen Olsvik was HiH’s last rector and her last year was mainly devoted to the process of merging with UiT, which happened on 1 January 2016.

Inger Aksberg is a trained nurse, with a major in nursing science and a special degree in psychiatric nursing. She was inspired to sign up as a candidate for the rector position after serving one period as vice-rector. She believed Harstad College (HiH) needed new input and wanted to increase the competence in the female-dominated field of health and social care, where all the resources were tied up in lectures.

The ministry believed the college was close to being a “high school”, with great lectures but hardly any research. With the new, national requirements for bachelor programs, at least 25% of the academic staff were required to have the status of associate professor or professor. The college was forced to facilitate the formal competence development of its academic staff and make strategies for establishing research groups in certain fields. As if this was not challenging enough, the college also aimed to develop three new master programs.

During her period as rector, another national requirement arrived; all educational institutions had to create an independent system for quality assurance. This was a challenging internal process. However, through the joint efforts of students and staff members, HiH’s new quality assurance system was approved.

The first attempts to merge with UiT took place during Aksberg’s period. The college management prepared a proposal for a common platform for the two institutions, however, when the university wanted to change aspects of it, HiH withdrew the proposal. Thus, the first attempt for a merger stalled.

Olav Soleng was born in Narvik in 1947. This is also where he grew up. He studied to be a teacher and philologist on Stord Island, in Bergen and Trondheim. From 1972, he took a part-time position as a teacher at Narvik School of Engineering, and from 1974, he was hired full time. Two years later, he was already head of studies. He remained in his position when the school was integrated into the college structure and became Narvik College of Engineering, in the spring of 1978.

On 1 August 1989, Soleng was elected rector. Three years later he was re-elected but was appointed as a director in 1994 when the College of Engineering, the College of Civil Engineering and the College of Nursing merged and became Narvik College.

“The role as rector was obviously demanding. When we obtained our new status within the university and college structure, we were also required to develop new working plans, open up for research activities and make strategies for further development. This was new to most of us. During this period, there was also strong, external factors that pressured the institution to merge into a larger entity,” explains Soleng.

The struggle to establish a program of civil engineering (1990) and a program of nursing (1993/94) was challenging. Nevertheless, this was a period filled with optimism; the student numbers increased, and many new teachers of high competence were hired. A large recruitment to the program of civil engineering was prioritized through offering free preliminary courses and recruiting international students by setting up a quota-system with Russia and China. This gave the enterprise a good foundation.

“We also managed to secure a stable financial platform for our activities through working with the central government. The college had a strong economy during this period,” remembers Soleng.

It would become difficult to unite the different cultures that existed among the lecturers and researchers in the field of engineering and civil engineering. There were similar conflicts of interest between the fields of technology and nursing. The fact that these programs operated in separate buildings did not make matters easier, and they would not share facilities until several years later.