Biosystematics of Bibionomorpha (Diptera) in the Taiga and Tundra

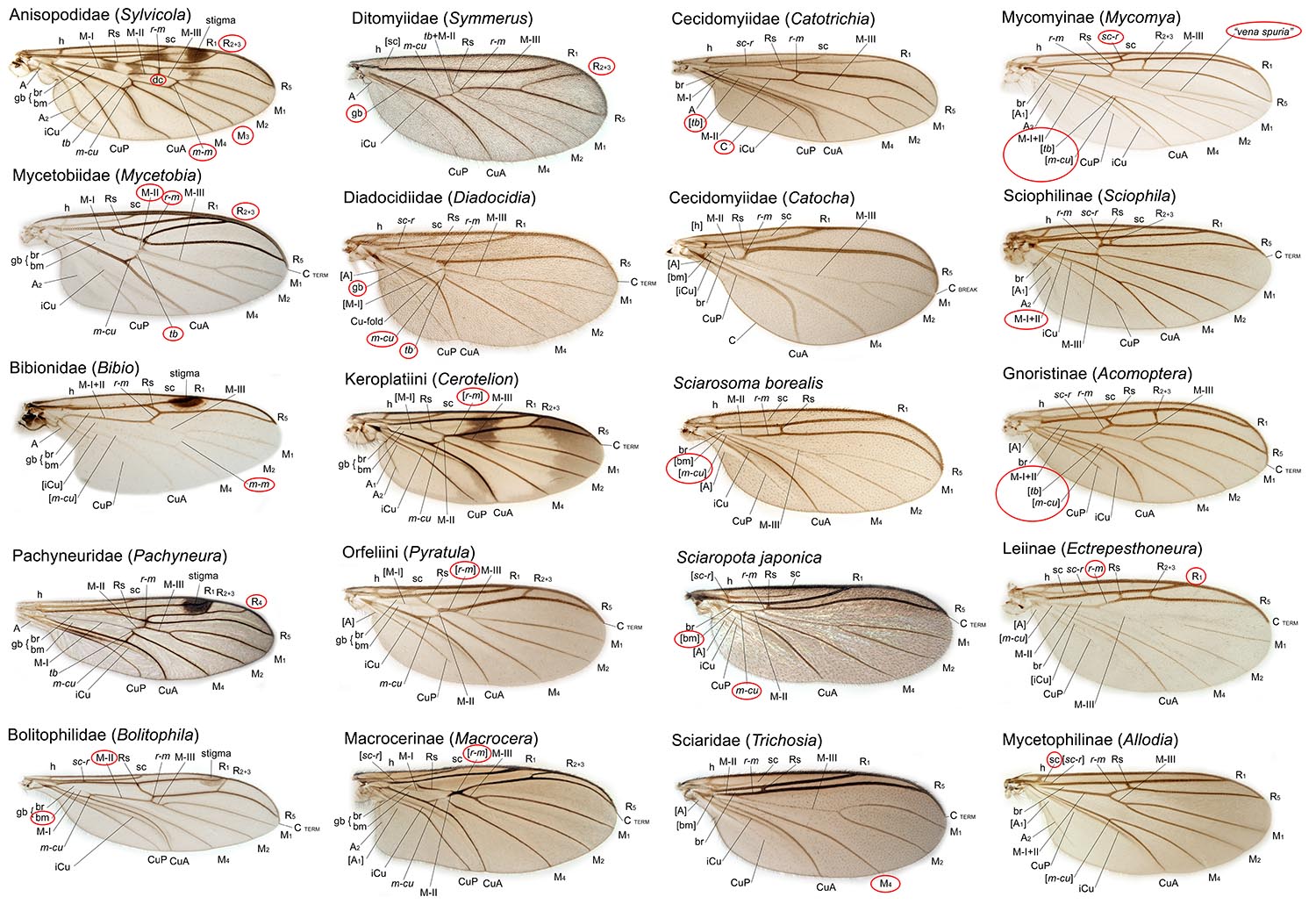

The infraorder Bibionomorpha (see recent molecular phylogeny by Sevcik et al. 2016) forms a monophyletic group of 17 extant and 17 fossil families of lower flies belonging to the insect order Diptera, the two-winged true flies. Our cross-university research group works to discover, enumerate and describe the rich northernmost fauna elements of the infraorder Bibionomorpha, the species living in the Taiga and Tundra biomes of the Holarctic Region.

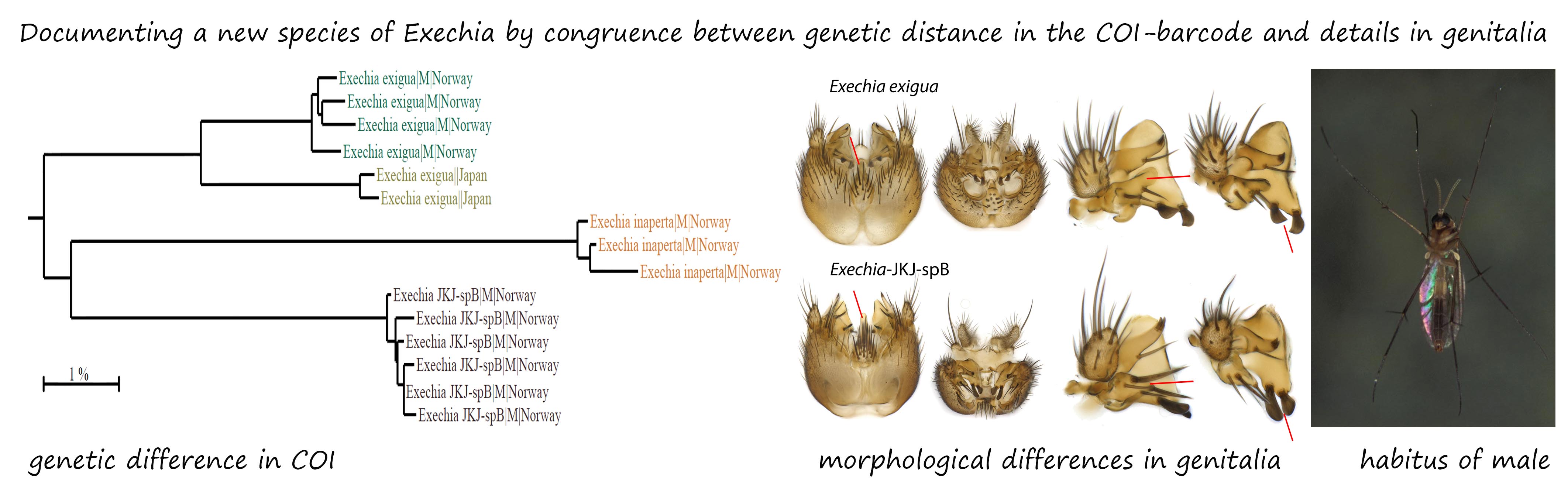

We use an integrative taxonomic approach combining morphology and genetic data, such as DNA-barcodes. In doing this we aim at a better understanding of both the evolutionary history of the group through an ever-changing climate in the north, and their more recent and current ecologically success in the circumpolar boreal taiga, the largest terrestrial biome on earth.

Pape et al. (2009) presented the first modern enumeration of the order Diptera, summarizing more than 163.000 valid species described in the world. The Bibionomorpha counts about 10% of all these flies, and three megadiverse families makes up most of the diversity in the infraorder; the gall midges, family Cedidomyiidae, with 6296 species in 761 genera; the fungus gnat family Mycetophilidae, with 4525 species in 233 genera; and the black fungus gnats, family Sciaridae, with 2455 species in 92 genera. The northern Taiga and Tundra holds a considerable proportion of this diversity, but the numbers above (from 2009) are already outdated as new species are continually being discovered and described from all over the world. With molecular methods, such as DNA barcoding, new techniques for species delimitation and enumeration are on the rise, sometimes with astonishing prospects on hidden species diversity even in the Holarctic Region. A recent publication by Herbert et al. (2016) highlights the genetic (COI) diversity of the family Cecidomyiidae as exceptionally high in Canada, indicating a tenfold species diversity compared to the currently known number of species.

- “The revelation of extremely high diversity within certain lineages of dipterans suggests that the long-standing recognition of Coleoptera as holding first place in the diversification race reflects a rush to judgement in a world of taxonomic uncertainty.”

- “The fact that the key drivers of animal diversity remain uncertain reveals the need to extend knowledge of biodiversity patterns and the variation in genetic systems that might influence them.”

Quotes about the Canadian fauna of insects, from Herbert et al. (2016)

Generally speaking the northern continents (i.e. the Holarctic Region) have a longer tradition for Diptera taxonomy, dating back all the way to the legacy of Linné, and especially the European fauna is, accordingly, relatively better known than the one in the southern continents that embrace the tropical realm. Jostein Kjærandsen updates on a regular basis the checklist of Nordic species of the families Bolitophilidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae and Mycetophilidae. Still, the northern boreal European fauna remains poorly investigated and hides an unknown proportion of species yet to be scientifically discovered, described and named, applying new integrative methods.

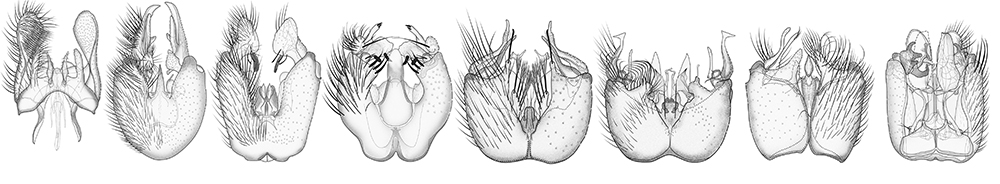

We are deeply fascinated by the immense morphological diversification in the genitalia of these small insect species, where virtually an explosion of beautiful three-dimensional shapes has taken place in the adult males of many groups. Although we still have only some vague clues to what drives the rapid morphological evolution in their genitalia, the complex structures makes it relatively easy for us to identify and separate closely related species under the microscope. Our results further points at a very good match between DNA-barcodes and genitalia structures.

At the same time, other body parts, such as their wings, have evolved in a much more morphologically constrained and phylogenetically conservative manner. These body parts give us valuable characters to study their deeper phylogenetic relationships, i.e. their older evolutionary history that took place through the last 200 million years and shaped the various families and genera. For this purpose DNA-barcodes falls short and other techniques and analytic tools using a broader spectrum of genes must be applied.

Initially, we focus mainly on the fungus gnat families Mycetophilidae and Bolitophilidae, both of which have their highest known diversity in the vast circumpolar taiga belt. Like the name indicates, the larval stage of fungus gnats feeds on fungal mycelium, in particular that of ectomycorrhizal fungi that also have their peak of diversity in the northern temperate regions. Once a better understanding of their biosystematics is established this opens up entirely new perspectives for studies of trophic interactions and food webs in the region.

In sum, these insects provide us with a fascinating but yet little known model system to study evolution in the Taiga and Tundra biomes, both short term in a perspective of changing climate and recent ice-ages, and in longer term through the development and movements of the continents and entire biomes.

In 2020 a Nordic-Baltic collaboration project called NORSCIID was esablished on TEAMS with the aims of producing a comprehensive monograph of all Nordic-Baltic Sciaroidea species belonging to the families Bolitophilidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae, Mycetophilidae and the genus Sciarosoma yet unplaced in family. This group is now approaching 1200 recorded Nordic-Baltic species and we are producing detailed phtographic plates for the identification of males for each one of them. The planned monograph is divided into five volumes intended for publication in European Journal of Taxonomy.

We collect insects at localities throughout the Nordic Region and study materials from available collections like the Swedish Malaise Trap Project (See Karlson et al. 2020). Collecting in Norway is mainly done through projects funded by the Norwegian Taxonomic Initiative (pages in Norwegian but rich in photos):

Project 1: Fungus gnats of Northern Norway (2018-2020)

Project 2: Northeastern elements of the Norwegian fauna of fungus gnats (2015-2017)

Project 3: The Diptera of Svalbard (2012-2015)

Project 4: DNA barcoding Holarctic Mycetophilidae (Diptera)

We have already built a solid reference library of mainly Nordic fungus gnats on BLOD (see Kjærandsen 2022) through NorBol – Norwegian Barcode of Life Project and FinBOL – Finnish Barcode of Life Project, both national networks of research institutions collaborating on DNA barcoding of organisms and regional nodes in the International Barcode of Life Project (iBOL).

Project 5: Molecular phylogeny of Bibionomorpha (Diptera)

This last project is led by Jan Sevcik's lab at University of Ostrava Ostrava, Czechia, where we collaborate on some publications.

Pictographic guide to the Nordic families of Bibionomorpha

Checklist of Nordic fungus gnats

Our major research issues concerns:

- To discover and describe the species living in the Western Palaearctic (Nordic) quartile of the Taiga and Tundra. We have already assembled materials of roughly 100 species that potentially are new to science, but many of them needs to be thoroughly compared with North American species (and DNA-barcode libraries) before they can be described.

- To contribute to build a complete DNA-barcode archive of the target taxa in the Taiga and Tundra biomes, with named and curated reference specimens deposited in museum collections.

- To develop new integrative phylogeographic and phylogenetic methods for testing species delimitation of the many circumpolar holarctic species complexes of fungus gnats, based in part by use of the huge database at The Barcode of Life Datasystem (BOLD) .

- To undertake taxonomic revisions including phylogentic analyses of selected taxa (species groups, genera) with a circumpolar distribution.

.