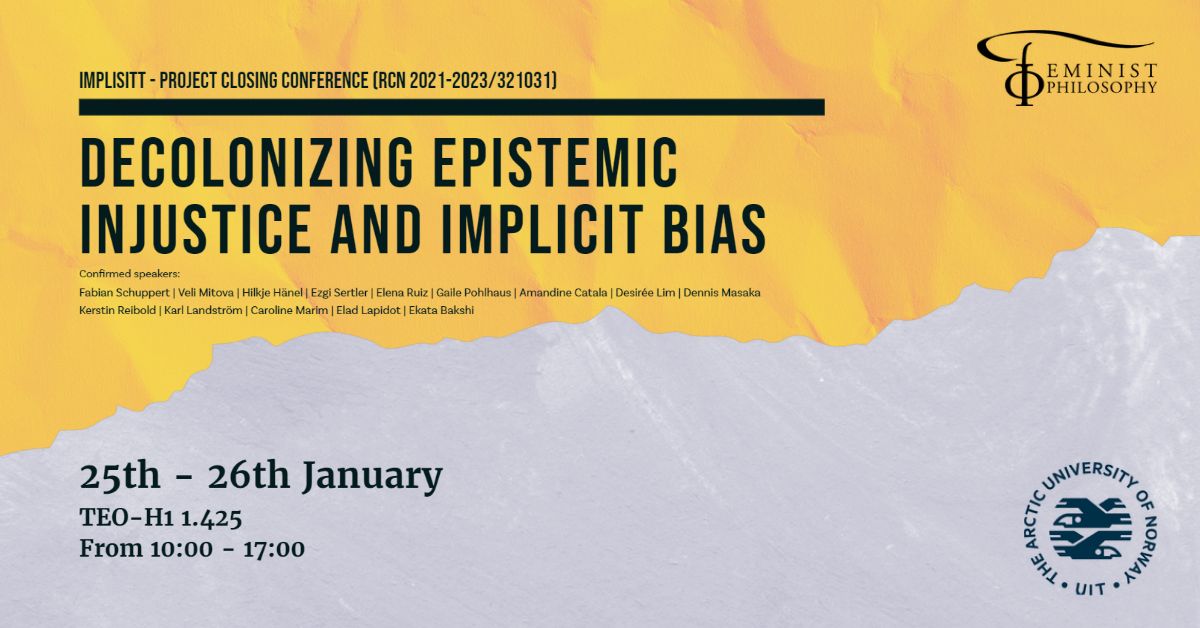

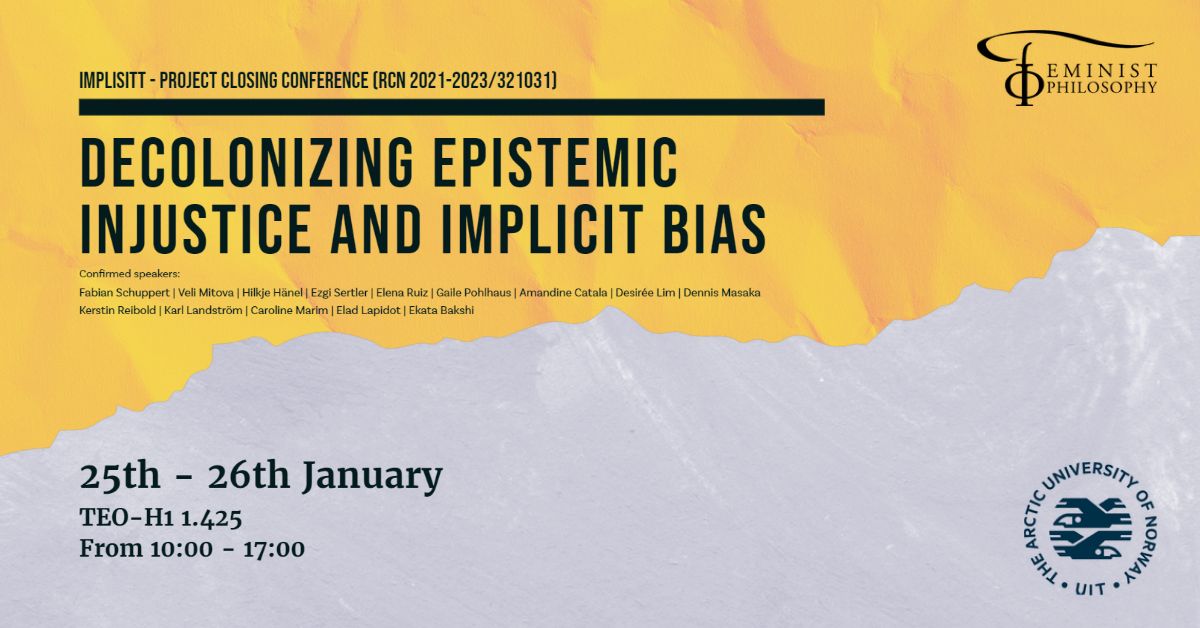

IMPLISITT - project closing conference: Decolonizing Epistemic Injustice and Implicit Bias

The two day closing conference establishes a connection between the topic of epistemic injustice and decolonial theories, which have so far been treated relatively separately. It thus contributes to making the cross-connections between the two topics obvious and thus accessible for further scientific analysis. It addresses three main questions of this important relationship:

While theories of epistemic injustice are have reached a wide audience and are being investigated in detail , as can be seen from the increasing number of books, papers, workshops, and seminars being offered on the topic, there is still little significant research on the intersection of epistemic injustice and decolonial theories. The edited collection is intended to contribute to closing three gaps in the academic discourse: (A) To highlight the importance of decolonial research in the field of epistemic injustice and to explore the relation between decolonial theory and theories of epistemic injustice; (B) to enrich the debate on epistemic injustice with non-Western experts on epistemology and/or decolonial theory; and (C) to critically investigate the ways in which the debate on epistemic injustice and our academic and, more generally, epistemic practices have to be decolonialized themselves.

Scroll down to sign up for the conference!

10:00 - 10:15 |

Welcome |

10:15- 11:00 |

Can Theorising Epistemic Injustice Help Us Decolonise?Veli Mitova

|

11:15 - 12:00 |

Epistemic Decolonization in the midst of Europe?Hilkje Hänel

|

12:00-13:15 |

Lunch |

13:15 - 14:00 |

Theories of Epistemic ColonialismEzgi Sertler & Elena Ruiz

|

14:15- 15:00 |

An Epistemology of the Oppressed: Resisting and Flourishing under Epistemic OppressionGaile Pohlhaus

|

15:15 - 16:00 |

Decolonizing Social Memory: Epistemic Injustice and Political EqualityAmandine Catala

|

16:15 - 17:00 |

Substantive and Procedural Epistemic InjusticeDesirée Lim

|

18:30-21:00 |

Dinner |

9:00 - 9:15 |

Welcome |

9:15 - 10:00 |

Overcoming Epistemic Injustice in Africa: A Global South PerspectivDennis Masaka

|

10:15 - 11:00 |

Knowledge-specific forms of epistemic injustice and the remnants of colonialismKerstin Reibold

|

11:15 - 12:00 |

On Epistemic Freedom and Epistemic InjusticeKarl Landström

|

12:00 -13:00 |

Lunch |

13:15 - 14:00 |

Decolonizing Epistemic Injustice: Ambivalent or Multiple Borders?Caroline Marim

|

14:15 - 15:00 |

Europe’s Suppressed Jewish EpistemeElad Lapidot

|

15:15 - 16:00 |

In Search of a “Truly-Feminist” Agency?Rethinking Feminist Epistemology in the Context of Partition-Induced Forced Migration in India Ekata Bakshi

|

16:15 - 17:00 |

Decolonising climate justice: On the epistemic injustice of neo-colonial climate politicsFabian Schuppert

|

18:30 - 21:00 |

Dinner |

Can Theorising Epistemic Injustice Help Us Decolonise?

Veli Mitova

According to some philosophers, the debate on epistemic injustice is (to put it crudely) ‘white-people stuff’: it reinforces the very structures of oppression and marginalisation that it supposedly aims to unravel. If this is right, theorising epistemic injustice is inimical to the decolonial project. In this paper, I argue that while this problem indeed bedevils some scholarship on epistemic injustice, there is nothing intrinsically marginalising about thinking in terms of such injustice. On the contrary, the debate has some good precision tools for diagnosing and combatting deep challenges for the oppressed. I take the decolonisation of knowledge as a point in case. I first sharpen the white-people-stuff objection. I then foreground three notions from the epistemic injustice literature – epistemic oppression, white ignorance, and contributory injustice – and argue that these notions are both useful for the decolonisation of knowledge and invulnerable to the white-people-stuff objection.

Epistemic Decolonization in the midst of Europe?

Theories of Epistemic Colonialism

Ezgi Sertler & Elena Ruiz

We start this paper with two diagnostic questions: 1. What is the nature and the purpose of the work of epistemic injustice, as the term becomes more and more ubiquitous in many academic projects? And 2. What is the nature and the purpose of the work of decolonizing epistemic injustice? The first question probes critical as well as creative potential of the term epistemic injustice and the limits of its non-structural projects. Answering the second question, we argue, requires both an investigation of the terms under which the work of decolonization is performed and an inquiry into how decolonization is understood, by whom, and for whom.

In light of these inquiries, we first demonstrate how the project of decolonizing epistemic injustice can itself be a colonial project. It can specifically be a colonial epistemological project that structures the terms of engagement between dominant and non-dominantly situated knowers through a hermeneutic pay-to-play exchange that recenters the terms, epistemic concerns, languages, and conceptual orthodoxies of Anglo-European intellectual traditions and their feminist inheritors and beneficiaries in philosophy. Here, we draw parallels to projects such as ‘decolonizing Aristotelian political philosophy’ and ‘decolonizing Rawls’ and ask: How are these projects relevant to the rematriative, reciprocal, reparative, restorative, and structural justice projects of Indigenous people and people of color in settler colonial societies who are actively trying to dismantle the vast reaches of European settler colonial whiteness and settler white supremacist violence in our lives? In other words, we question the value, but more importantly, the purposes of the epistemic labor that goes into enumerating and extracting non-whitewashed versions of whitewashed theories of injustice. Here, we also investigate whether this kind of project can decouple people’s colonial education from serving the interests of the culture that propagated that system of education.

We track the histories of long-standing theoretical traditions in Indigenous and women of color feminisms in order to demonstrate a project of decolonizing epistemic injustice with different orientations. We argue that these particular theoretical traditions offer non-deal framings of epistemic injustice as epistemic colonialism, where the norms of prioritization are written and enacted differently than a hermeneutic pay-to-play exchange. We identify discussions and theorizations of structural epistemic violence as an impactful systemic force in women’s lives by multiple feminist theories in the global south, and we argue that these projects of structural epistemic violence work tirelessly to highlight mechanisms of corruption, destruction and silencing in colonial epistemological systems.

An Epistemology of the Oppressed: Resisting and Flourishing under Epistemic Oppression

Gaile Pohlhaus

Decolonizing Social Memory: Epistemic Injustice and Political Equality

Amandine Catala

Most western democracies have been, or continue to be, involved in colonialism. Yet colonial memory is often either severely distorted or lacking entirely – a situation I characterize as “colonial erasure.” I argue that, by obscuring the continuity between historical and contemporary injustice, colonial erasure produces and maintains inequalities in both epistemic and political power for Afrodescendants and Indigenous peoples. Specifically, I argue that colonial erasure creates epistemic injustice; that this situation of epistemic injustice undermines political equality in contemporary societies; and that securing epistemic justice and political equality therefore requires, among other things, a collective duty of colonial memory. I proceed in three steps. I first point to the mechanisms that underlie colonial erasure by looking at the functions that social memory serves for social groups, and I show how defective social memory regarding colonialism produces and maintains epistemic injustice for Afrodescendants and Indigenous peoples. I then argue that this situation of epistemic injustice seriously undermines these minorities’ ability to engage in the democratic process of political participation on an equal basis. In this way, colonialism very much continues into the present. Ending colonial domination and achieving political equality thus require, among other things, bringing about epistemic justice through colonial memory. Finally, I specify what the collective duty of colonial memory involves and the processes whereby it might be fulfilled. Here I show how an understanding of the different functions that social memory serves can help to identify effective strategies to fulfill the collective duty of colonial memory, and hence to move toward greater epistemic justice and political equality.

Substantive and Procedural Epistemic Injustice

Overcoming Epistemic Injustice in Africa: A Global South Perspectiv

Dennis Masaka

In this chapter, I seek to show how the problem of epistemic injustice in Africa could best be approached in a way that will possibly lead to the attainment of envisioned genuine epistemic justice. I particularly posit that substantive attention ought to be focused on how knowledge production in Africa could be recast so that the knowledges that are produced identify with existential situations of their producers. This dimension has largely been under-emphasised in debates about epistemic injustice in Africa which have so far focused more on showing the merits of counterbalancing the stake of the dominant knowledge tradition of our time in learning arenas through creating space for other knowledges. In the first section, I attempt to indicate what African peoples typically regard as epistemic injustice and how it has constrained the flourishing of their epistemologies. In the second section, 1 highlight what has been commonly believed in extant literature to be viable solutions to this problem. In the final section, I attempt to show what possibly needs to be done to attain genuine epistemic justice in Africa, that is, ensuing that the knowledges that are produced reflect the aspirations and terms of cultures from which they emerge. The overall objective is to offer a proposal from a typical global South perspective that, on balance of scale, offer a compelling basis on which to ground efforts to overturn epistemic justice and engender epistemic justice.

Knowledge-specific forms of epistemic injustice and the remnants of colonialism

Kerstin Reibold

Successful integration often hangs on whether trust can be established between the native and the immigrant population. Trust, in turn, is related to different forms of knowing. Trusting someone means, among other things, to believe that the other person has not just the will but also the knowledge to fulfill whatever one is trusted with (competences, norms etc.). This chapter analyzes how prejudices about former colonial subjects and their assumedly lower competence, differing norms and nature still influence whether immigrants that can be visibly identified as belonging to a former ‘colonial population’ are believed when they communicate their trustworthiness. The chapter argues that colonial prejudices are fostering different kinds of epistemic injustice that directly undermine the establishment of trust, and thus integration, of immigrants in Western states.

On Epistemic Freedom and Epistemic Injustice

‘Seek ye epistemic freedom first’ is how Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni begins his book Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization (2018:1). The book constitutes a nuanced study of the politics of knowledge, and particularly of the African struggle for epistemic freedom. In the opening stages of the book Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018:3) develops an account of epistemic freedom as the right to think, theorize and develop one’s own methodologies to interpret the world, and write from where one is located unencumbered by Eurocentrism. He argues that extant struggles for epistemic freedom stem from the continued entrapment of knowledge production in Africa within Euro- and North America centric matrices of power, and that control of the domain of knowledge production is central to the maintenance of asymmetric global power structures. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) describes his project as one driven by a restorative epistemic agenda centred around epistemological decolonisation, provincializing Europe, and deprovincializing Africa. He argues that epistemic freedom speaks directly to what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2014) has called cognitive justice. That is the recognition of the diverse ways of knowing by which humans from across the globe make sense of their experiences. In this chapter I explore the intersection of Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s account of epistemic freedom with a different set of theories pertaining to justice and injustice in the epistemic realm, namely the theorizing of epistemic injustice and epistemic oppression. In doing so I demonstrate that Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s theory of epistemic freedom, and theories of epistemic injustice and oppression intersect. Further I argue that they are complementary and can be fruitfully combined both to theorize and expose unjust conditions and structures that shape epistemic lives and practices. Further I argue that doing so will serve ameliorative and, in the words of Ndlovu-Gatsheni, restorative purposes.

Decolonizing Epistemic Injustice: Ambivalent or Multiple Borders?

Europe’s Suppressed Jewish Episteme

Elad Lapidot

The chapter addresses the restitution of Europe's suppressed Jewish episteme. The contribution will concern, examine and critique contemporary projects that try to carry out something like a decolonization of Jewish Studies, which seek to undo the reification of "the Jewish" as an object of modern science, and to retrieve an alternative Jewish episteme and epistemology. Among others, my contribution will examine the tension between properly postcolonial projects of non-European epistemes and the decolonization of Jewish Studies, which approaches the Jewish episteme not as non-European but as an inner other to Christian Europe. The authors I will deal with include writers such as Emmanuel Levinas, Benny Lévy, Jonathan and Daniel Boyarin and Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin.In Search of a “Truly-Feminist” Agency? Rethinking Feminist Epistemology in the Context of Partition-Induced Forced Migration in India

Fabian Schuppert