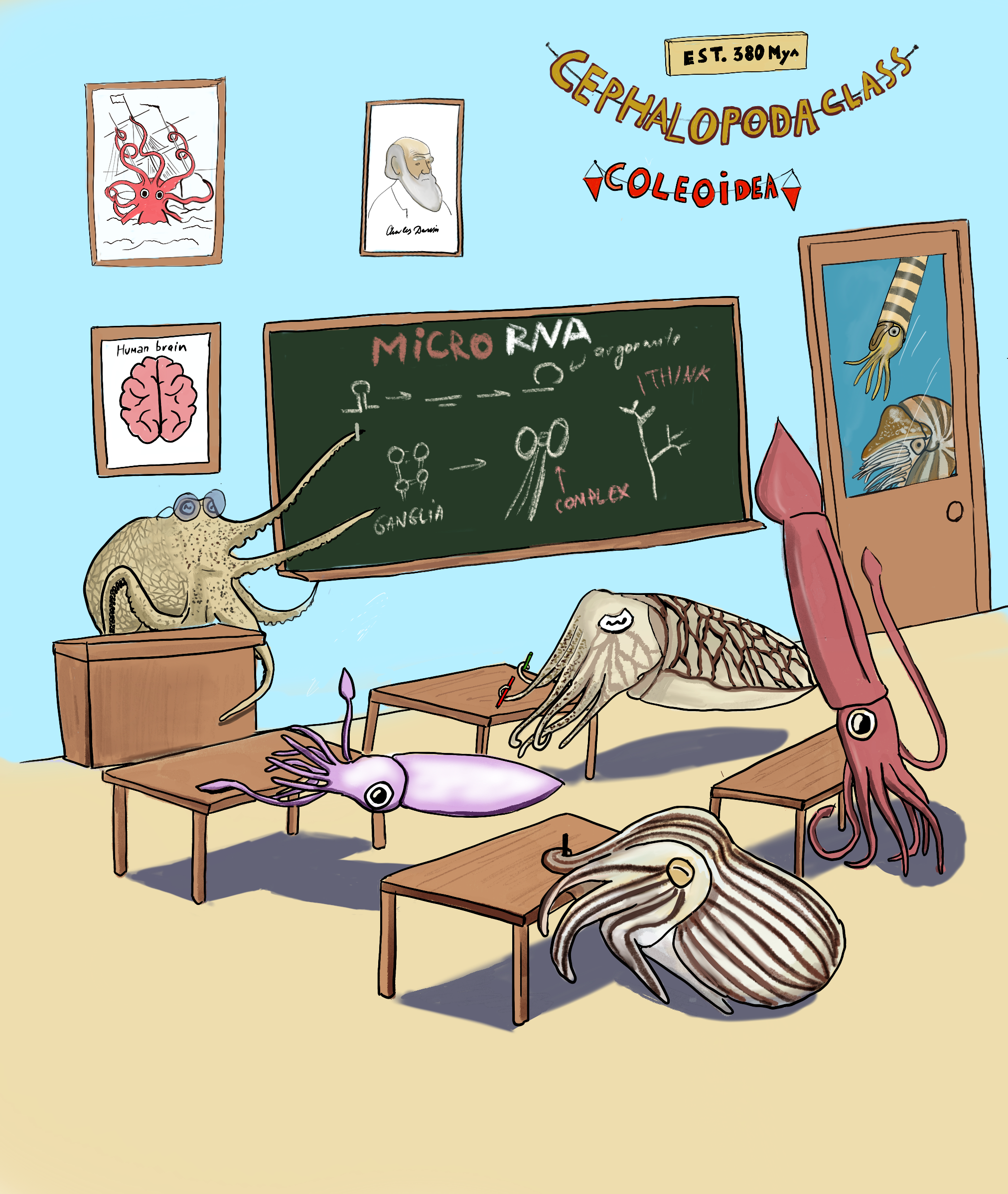

Solving the puzzle of the octopus’ brain

Octopuses have been shown to solve problems and unscrew the lid of a jar to get food. But what makes this animal so intelligent? Scientists may have found the solution to this conundrum.

About 20 years ago, scientists managed to put together the entire “cookbook” of all DNA recipes to make a human – the human genome. And after this, the researchers have managed to collect the genomes of 6,500 animals from all over the world, so that we now know all the recipes for all the characteristics of these animals. These complete genomes allow us to compare different organisms to learn about the molecular basis of an endless variety of animal forms.

– Despite initial expectations, these genomes show that animal DNA is strikingly similar among different species. For example, a sponge in the sea has several genes that are like those of humans, mice or flies, says researcher Bastian Fromm at UiT Norway's Arctic University.

Therefore, researchers are now trying to find the explanation for the differences in the animal world elsewhere, namely in the RNA in our cells. And what they find is surprising.

The octopus' Secret

Despite a largely similar recipe book, it seems the creation of animals happens in different ways by adding a different numbers of cell types. This is particularly evident in organisms with high cognitive abilities and complex behavior such as humans and octopuses.

In a recent research study published in the journal Science Advances, Bastian Fromm collaborated with colleagues from Ukraine, the UK, Italy, Belgium, the US and Germany to study RNA biology in octopus.

The researchers hoped to find out the secret behind the octopus' behavior by determining the sequence of the RNA of 18 different tissues and brain areas of a common octopus. This is called sequencing.

– We had a published genome and a few studies looking at some parts of the RNA in octopus, but nothing convincing was out there. Therefore, we decided to study the entire RNA from multiple different tissues at once, explains Grygoriy Zolotarov, first author of the study.

Genes switched on or off

RNA are small molecules in the cell that have important tasks in the production of proteins and contribute to which genes are switched on and off in animals. RNA is found in all cells of all organisms, just like DNA. But unlike DNA, which is double-stranded, RNA is single-stranded. RNA is made from recipes in the DNA.

There are several different kinds of RNA in cells. The best known is mRNA which acts as an intermediary between genes and all the characteristics of the individual. When proteins are made in the cell, the gene is first translated from DNA to mRNA. This can lead to new forms of proteins and creates more diverse proteins.

Another type of RNA is called microRNA. This is what Bastian Fromm is researching. He leads a group that studies evolution and microRNA at UiT The Arctic University Museum of Norway. Scientists believe that microRNAs are the molecules responsible for making new and specialized cells, especially nerve cells.

– MicroRNA act as light switches, or dimmers that regulate exact amounts of proteins in our cells that play key roles in cell type determination and the evolution of complexity, says Fromm.

Until recently, none of these processes had been studied in octopus, and it was unclear what drives the complexity of the cognitive abilities in this unique animal. The cognitive abilities are the resources in the brain related to thinking and understanding.

Large amounts of microRNA

The first analyses carried out by Zolotarev and his colleagues in the laboratory in Berlin were disappointing. But when Bastian Fromm and his collaborator Kevin J. Peterson from Dartmouth College in the USA, began to analyze the microRNA data, the researchers were surprised:

– When we ran our first analyses on the octopus data, we thought there must be something wrong with our equipment. These guys had more microRNAs than birds, says Fromm.

This explains how it is possible that octopuses are more intelligent than most birds. It appears that the number of microRNAs animals have in their brains determines how intelligent they are. And octopuses have large amounts of microRNA!

– This is incredible, because we know that intelligence has only developed independently twice throughout evolution, and both times this process appears to be driven by microRNA, says Fromm.

Studying octopus embryos

– Our analysis confirmed that octopus has the largest expansion of microRNA that we know outside the world of mammals, says Peterson.

So, what is this massive microRNA toolkit used for?

Most new microRNAs are expressed in the nervous system of octopus. Which confirms the animal’s high intelligence and ability to learn.

Excited by this observation, the team collected additional data from developing embryos from octopus.

It turns out that embryos have the highest proportion of new microRNAs. This indicates that microRNAs play a central role in creating different types of cells during development, says Fromm.

– This study is a milestone when it comes to understanding the complexity of organisms and confirms that shining the spotlight on microRNAs for future research is useful for understanding more about why animals are so incredibly different, says Fromm.

-

Fiskeri- og havbruksvitenskap - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Fiskeri- og havbruksvitenskap - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Akvamedisin - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Bioteknologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Arkeologi - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Geosciences - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Biology - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Physics - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Mathematical Sciences - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Biomedicine - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Public Health - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Computational chemistry - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Law of the Sea - master

Varighet: 3 Semestre -

Biologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Medisin profesjonsstudium

Varighet: 6 År -

Nordisk - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Luftfartsfag - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Pedagogikk - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Bioingeniørfag - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Informatikk, datamaskinsystemer - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Informatikk, sivilingeniør - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Likestilling og kjønn - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Geovitenskap- bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Biomedisin - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Psykologi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Samfunnssikkerhet - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Matematikk - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Ergoterapi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Fysioterapi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Radiografi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Samfunnssikkerhet - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Farmasi - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Farmasi - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Romfysikk, sivilingeniør - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Bærekraftig teknologi, ingeniør - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Psykologi - årsstudium

Varighet: 1 År -

Odontologi - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Tannpleie - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Anvendt fysikk og matematikk, sivilingeniør - master

Varighet: 5 År -

Sykepleie - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Barnevern - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Sosialt arbeid - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Idrettsvitenskap - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Sosialt arbeid - master

Varighet: 2 År -

Praktisk-pedagogisk utdanning for trinn 8-13 - årsstudium

Varighet: 2 År -

Vernepleie - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Internasjonal beredskap - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Barnevern - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År -

Vernepleie - bachelor

Varighet: 4 År -

Ernæring - bachelor

Varighet: 3 År