Internship at Njord Centre Oslo

I am pleased to describe to you what has so far been a successful and engaging internship. John Aiken has been an enthusiastic supervisor with a clear plan to make the most out of limited time. I have spent the past several weeks working on a novel geophysics problem and taking advantage of the opportunity to explore some of Norway’s historical sites in my free time.

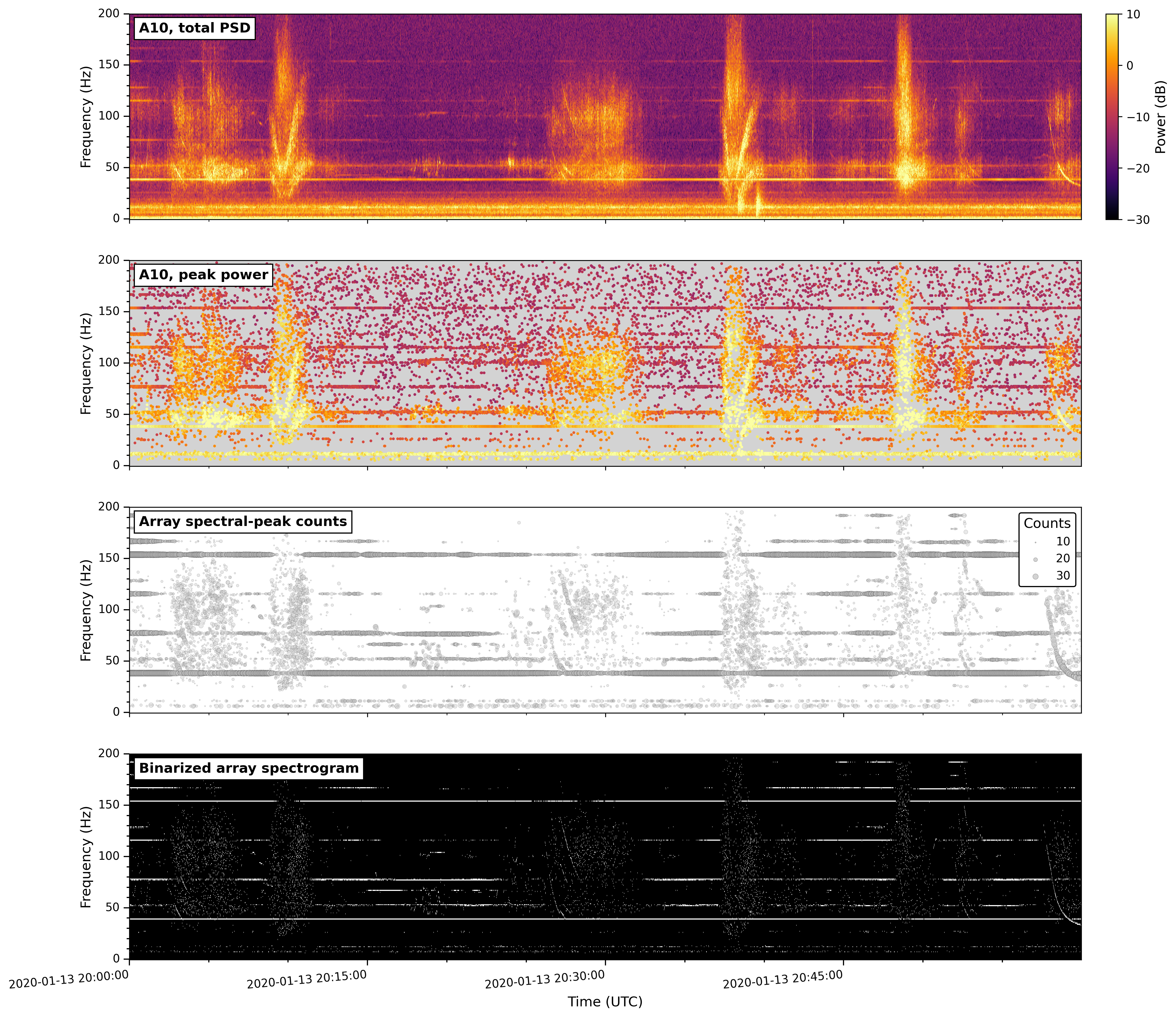

Long before I arrived in Norway, the group has been interested in data from the Oman Drilling Project. The hydrophone and geophone array deployed in the project’s Multi-Borehole Observatory had noticed signs of bubbling that could be attributed to peridotite serpentinization—which could play a role in carbon sequestration. Further analysis of the borehole data had revealed several unexpected and as of yet unidentified patterns in the spectrogram data.

The major difficulty in identifying these seemingly new phenomena is the sheer magnitude of the dataset. With a couple dozen geophones taking constant readings for two months, even loading in the dataset to look at takes a non-trivial amount of time. So, John Aiken had the idea to use machine learning to explore the data in a more systematic way, and that is why I am here.

I am not trained as a geophysicist, but three years of physics undergrad has put me in great place to tackle the problem. First and foremost, I have had repeated experience manipulating waveform data and using Fourier transforms. I also came in very familiar with machine learning and fluent in the coding needed to implement it.

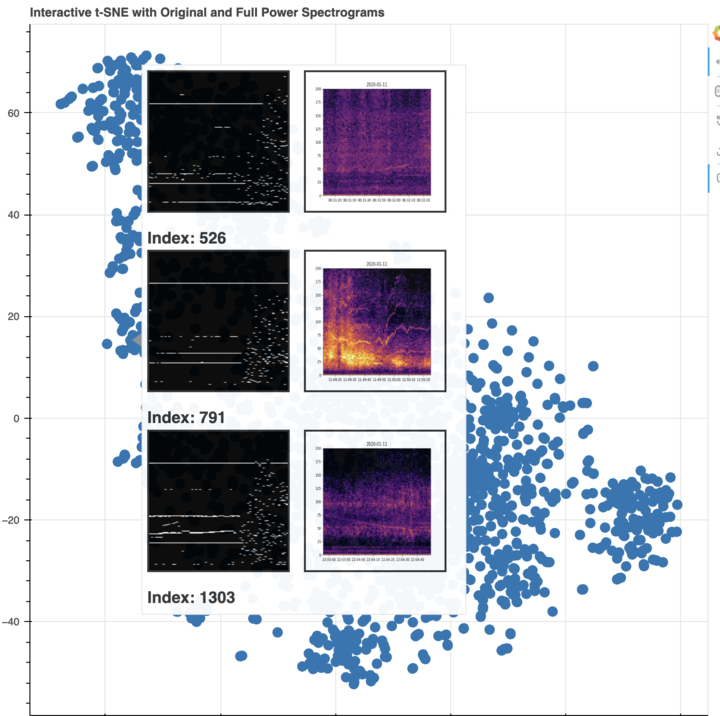

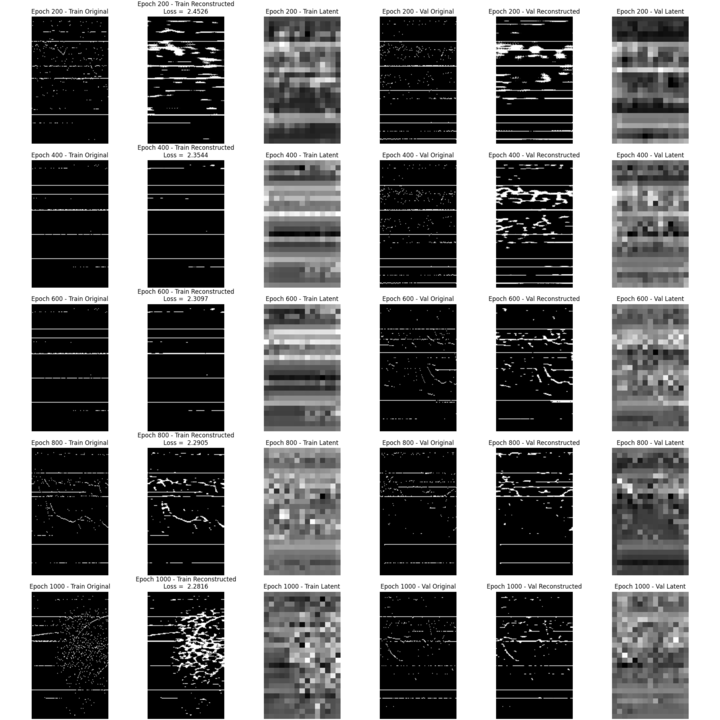

The plan for the internship had three main parts: train an autoencoder on spectrogram data to represent the most fundamental features of spectrogram windows; feed the autoencoder into a clustering software; and visualize the cumulative occurrences of the many classes created by the autoencoder. This is a type of unsupervised clustering. The difficulty lies in the tendency of unsupervised models to capture unimportant features since they are not being directed towards learning anything specific.

Fortunately I have had the knowledge of a great interdisciplinary team to draw on. Tianze was responsible for creating and maintaining the database of spectrograms. This includes several built-in functions for accessing and manipulating those spectrograms. In the early days of the internship, we worked closely together to troubleshoot any issues with the dataset so I could get started on implementing the autoencoder and clustering as fast as possible.

Meanwhile, Karina as a geophysicist had much better domain knowledge than I did coming in. In training the autoencoder it was useful, to consult her and the rest of the group to see if the features being captured were ones that were physically relevant. One especially relevant insight was that many of the horizontal lines in the data were stationary resonances that although not uninteresting were already well understood by the group and could be ignored.

In the last several weeks we discussed issues frequently and I gave a couple of presentations when results came in. All the while John and I went back and forth iterating on ways to make the autoencoder or subsequent clustering faster and more effective. I read up on related papers while waiting for scripts to run and went to a couple talks to familiarize myself with the field more, and overall I would describe the internship as an amazing opportunity to apply my expertise to an area that I did not have as much familiarity.

Best,

Benjamin Mellon